These high school “classics” have been taught for generations – could they be on their way out?

If you went to high school in the United States anytime since the 1960s, you were likely assigned some of the following books: Shakespeare’s “Romeo and Juliet,” “Julius Caesar” and “Macbeth”; John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men”; F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby”; Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird”; and William Golding’s “The Lord of the Flies.”

For many former students, these books and other so-called “classics” represent high school English. But despite the efforts of reformers, both past and present, the most frequently assigned titles have never represented America’s diverse student body.

Why did these books become classics in the U.S.? How have they withstood challenges to their status? And will they continue to dominate high school reading lists? Or will they be replaced by a different set of books that will become classics for students in the 21st century?

The high school canon

The set of books that is taught again and again, broadly across the country, is referred to by literature scholars and English teachers as “the canon.”

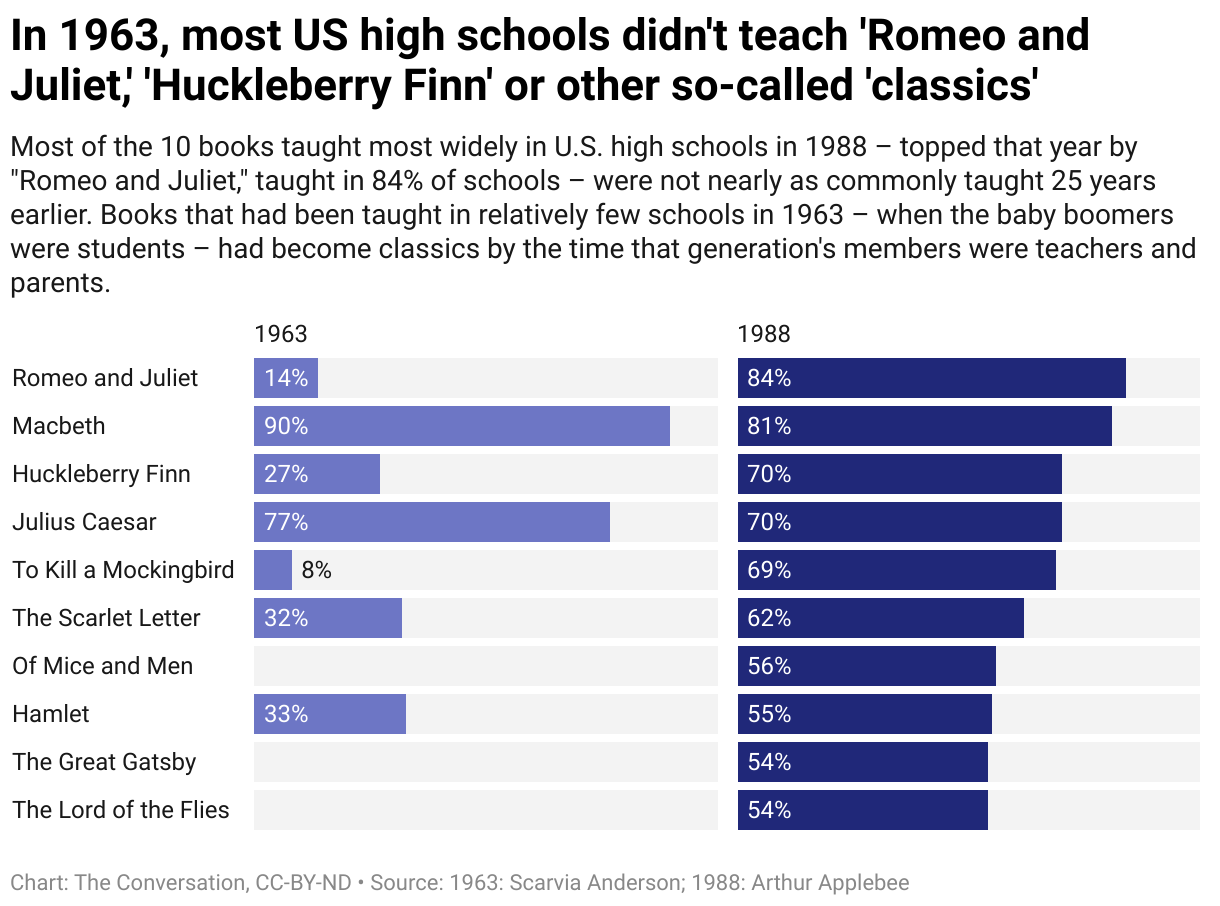

The high school canon has been shaped by many factors. Shakespeare’s plays, especially “Macbeth” and “Julius Caesar,” have been taught consistently since the beginning of the 20th century, when the curriculum was determined by college entrance requirements. Others, like “To Kill a Mockingbird,” winner of the 1961 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, were ushered into the classroom by current events – in the case of Lee’s book, the civil rights movement. Some books just seem especially suited for classroom teaching: “Of Mice and Men” has a straightforward plot, easily identifiable themes and is under 100 pages long.

Titles become “traditional” when they are passed down through generations. As the education historian Jonna Perrillo observes, parents tend to approve of having their children study the same books that they once did.

The last period of significant change to the canon was during the 1960s and 1970s, when the largest generation of the 20th century, the baby boomers, went to high school. For instance, in 1963, a survey of 800 students at Evanston Township High School in Illinois revealed that “To Kill a Mockingbird,” first published in 1960, was by far the “most enjoyed book,” followed by two books that had been published in the 1950s, J.D. Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye” and Golding’s “The Lord of the Flies.” None of these books were yet traditional, yet they became so for the next generation.

A comparison of national surveys conducted in 1963 and 1988 shows how several books that were introduced to the classroom when the boomers were students had become classics when boomers were teachers.

During the 1960s and 1970s, teachers even reframed “Romeo and Juliet” as a contemporary work. Lesson plans from the era referred to its adaptations into “West Side Story” – a musical that initially came out in 1957 – and Franco Zefferelli’s risqué 1968 film version of Shakespeare’s story of star-crossed lovers. It became the perfect hook for ninth graders in a study of Shakespeare that would conclude in 12th grade with “Macbeth.”

Efforts to diversify

English education professor Arthur Applebee observed in 1989 that, since the 1960s, “leaders in the profession of English teaching have tried to broaden the curriculum to include more selections by women and minority authors.” But in the late 1980s, according to his findings, the high school “top ten” still included only one book by a woman – Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” – and none by minority authors.

At that time, a raging debate was underway about whether America was a “melting pot” in which many cultures became one, or a colorful “mosaic” in which many cultures coexisted. Proponents of the latter view argued for a multicultural canon, but they were ultimately unable to establish one. A 2011 survey of Southern schools by Joyce Stallworth and Louel C. Gibbons, published in “English Leadership Quarterly,” found that the five most frequently taught books were all traditional selections: “The Great Gatsby,” “Romeo and Juliet,” Homer’s “The Odyssey,” Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” and “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

One explanation for this persistence is that the canon is not simply a list: It takes form as stacks of copies on shelves in the storage area known as the “book room.” Changes to the inventory require time, money and effort. Depending on the district, replacing a classic might require approval by the school board. And it would create more work for teachers who are already maxed out.

“Too many teachers, probably myself included, teach from the traditional canon,” a teacher told Stallworth and Gibbons. “We are overworked and underpaid and struggle to find the time to develop quality lessons for new books.”

The end of an era?

Esau McCauley, the author of “Reading While Black,” describes the list of classics by white authors as the “pre-integration canon.” At least two factors suggest that its dominance over the curriculum is coming to an end.

First, the battles over which books should be taught have become more intense than ever. On the one hand, progressives like the teachers of the growing #DisruptTexts movement call for the inclusion of books by Black, Native American and other authors of color – and they question the status of the classics. On the other hand, conservatives have challenged or successfully banned the teaching of many new books that deal with gender and sexuality or race.

PEN America, a nonprofit organization that fights for free expression for writers, reports “a profound increase” in book bans. The outcome might be a literature curriculum that more resembles the political divisions in this country. Much more than in the past, students in conservative and progressive districts might read very different books.

Second, English Language Arts education itself is changing. State standards, such as those adopted by New York in 2017, no longer make the teaching of literature the primary focus of English class. Instead, there is a new emphasis on “information literacy.” And while preceding generations of teachers voiced concerns about the distractions of radio and then television, books may have an even smaller share of students’ attention in the age of cellphones, the internet, social media and online gaming.

“We no longer live in a print-dominant, text-only world,” the National Council of Teachers of English proclaims in a 2022 position statement. The group calls for English teachers to put less emphasis on books in order to train students to use and analyze a variety of media. Accordingly, students across the country may not only have fewer books in common, but they also may be reading fewer books altogether.

Why teach literature?

Over generations, English teachers have voiced many reasons to teach books, and the canon in particular: to instill a common culture, foster citizenship, build empathy and cultivate lifelong readers. These goals have little to do with the skills emphasized by contemporary academic standards. But if literature is going to continue to be an important part of American education, it is important to talk not only about what books to teach, but the reasons why.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.