Attacking a priceless work of art doesn’t make you an iconoclast

- Iconoclasm is the deliberate destruction of symbols or visual icons that are considered meaningful to others.

- During the Beeldenstorm of the 16th century, Protestant rioters across northwestern Europe tore down Catholic art work.

- When studying iconoclasm and violence against art, it is important to consider the motivation behind the act.

In recent weeks, it has become a trend among climate activists to attack famous paintings in galleries around the world.

In just the month of October, Australian activists from Extinction Rebellion glued their hands to Picasso’s Massacre in Korea at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne (October 8); members of Just Stop Oil hurled tomato soup at Vincent van Gogh’s Fifteen Sunflowers in London (October 14); Letzte Generation in Potsdam covered Claude Monet’s Haystacks in mashed potatoes (October 23); and one Just Stop Oil activist glued his bald head to Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, Netherlands (October 27).

Some have labeled these activists “iconoclasts“: people who damage or destroy symbols and visual icons that others consider meaningful. This comparison, while tempting, isn’t entirely accurate. One reason is that none of the paintings were actually harmed; activists either targeted works that are protected by glass, or glued themselves to frames or the adjacent walls.

More importantly, however, the attacks cannot be considered examples of iconoclasm because they were not aimed at the art itself, but at what the activists perceive to be public indifference toward climate change. After attaching themselves to Picasso, the activists from Melbourne unfolded a banner reading “CLIMATE CHAOS = WAR + FAMINE.” Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland, who targeted van Gogh, had a similar message. “The cost of living crisis is part of the cost of oil crisis,” they shouted. “Fuel is unaffordable to millions of cold, hungry families. They can’t even afford to heat a tin of soup.” (This argument seems self-contradictory, since stopping oil would make fuel even more unaffordable.)

The protestors at the Mauritshuis asked onlookers how they felt when they saw “something beautiful and priceless apparently being destroyed before your eyes.” When someone told them they should be ashamed of themselves, they responded: “Where is that feeling when you see the planet being destroyed?”

“The eco-activists want to appear to desecrate something that people associate with value and with culture,” Sally Hickson, an associate professor of art history at the University of Guelph, explains in an article for The Conversation. “Their point is that if we don’t have a planet, we’ll lose all the things in it that we seem to value more.”

Rather than destroying paintings, these activists are using art to communicate a powerful message of their own. Jakob Beyer and Maike Gruns, members of Letzte Generation who glued themselves to the decorated gold frame containing Raphael’s Sistine Madonna in the Old Masters Picture Gallery in Dresden, picked the painting because Jesus and Mary’s fear of the future reflect the fears that members of Letzte Generation and other activist groups experience today. Similarly, activists from Italy’s Ultima Generazione chose the famed statue Laocoön and His Sons because, “like Laocoön, scientists and activists are the witnesses trying to warn those around them about the consequences today’s actions will have on the future. Like Laocoön, scientists and activists are not listened to.”

How to be an iconoclast

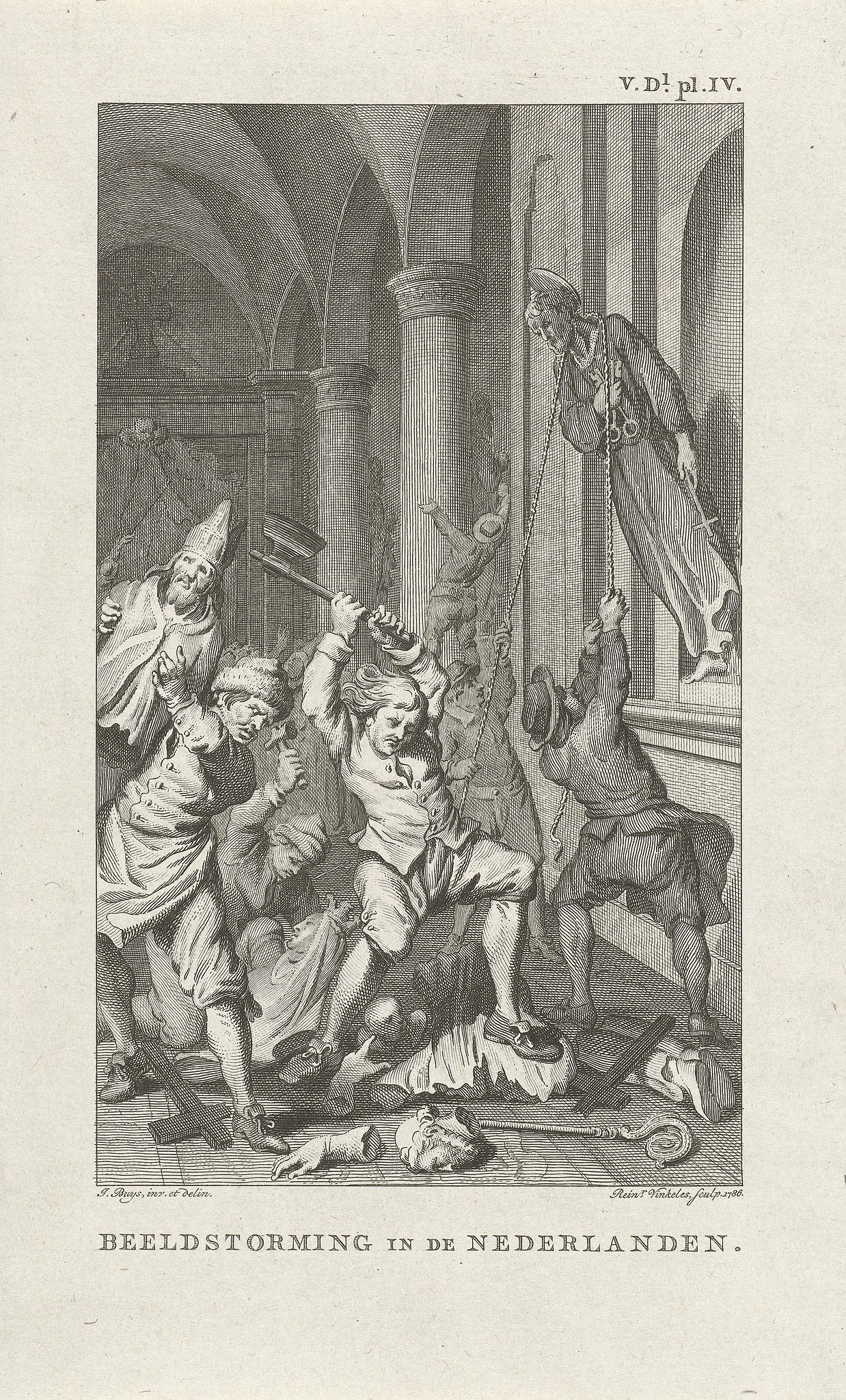

Whether you applaud or condemn the activists, this isn’t real iconoclasm. For a genuine example of what it is to be an iconoclast, look no further than the Beeldenstorm, a period of European history in which Protestant mobs across Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, and other countries destroyed an incalculable amount of Catholic art work.

Beeldenstorm is a Dutch word, reflecting the particularly important role the movement played in the history of the Low Countries, which were turned on their head when, on August 10, 1566, Calvinist rioters demolished the Saint Laurentius monastery in the Flemish town of Steenvoorde. Once unleashed, the storm took less than a week to reach the economic and cultural centers of Antwerp and Ghent, followed by the then-nascent town of Amsterdam.

The destruction was of biblical proportions, with “all the churches, chapels, and houses of religion utterly defaced,” recalled Richard Clough, a Protestant merchant from Wales. There was “no kind of thing left whole within them, but broken and utterly destroyed, being done after such order and by so few folks that it is to be marvelled at.” The Church of Our Lady in Antwerp, the biggest cathedral in the city, “looked like a hell, where were above 10,000 torches burning, and such a noise as if heaven and earth had got together, with falling of images and beating down of costly works, such sort that the spoil was so great that a man could not well pass through the church.”

According to one estimate, more than 400 churches were attacked in Flanders alone. However, as Clough mentions, these attacks were not aimed at the places of worship themselves, but the “costly works” displayed inside them. Unlike in other countries, where Protestant mobs routinely lynched clergymen as well, the ire of Dutch and Belgian iconoclasm was aimed exclusively at paintings, altar pieces, statues, and stained glass windows.

Why?

Some historians have interpreted the Beeldenstorm as a revolt against the Spanish Empire, a devoutly Catholic monarchy that at the time controlled much of northwestern Europe. Its king, Philip the Prudent, criticized the pacification edicts ratified by Charles IX, King of France, which allowed Protestants to express their faith under certain conditions. Fearing that concessions would only embolden the Calvinists, Philip refused to extend similar rights to the Low Countries. Ironically, it was precisely this refusal that ended up setting the stage for the Beeldenstorm. In his influential book Beggars, Iconoclasts, and Civic Patriots: The Political Culture of the Dutch Revolt, Peter Arnade points out that the Laurentius monastery — the place where the storm began — was dedicated to the same saint as Philip’s El Escorial palace near Madrid, which was completed the same year the attack in Steenvoorde took place.

Others view the Beeldenstorm as a distinctly religious and intellectual as opposed to political movement. After all, if the rioters desired freedom, they ought to have rebelled directly against the Spanish monarchy, not the local Catholic clergy. Following this train of thought, the Beeldenstorm could be interpreted as a continuation of the Protestant Reformation, which began decades earlier. Reformation leader Martin Luther had decried the power and prestige vested in Catholic artwork, which were commissioned through public donations and traded among the elite as tickets for eternal salvation. John Calvin rejected the conservative notion that art could enlighten those who were unable to read the scriptures. At best, paintings and statues were personal expressions of piety; at worst, they were false idols in service of religious institutions, not religion itself.

In summary, if the Beeldenstorm was indeed a revolt against Philip II and the Spanish Empire, this would mean that Protestant rioters attacked Catholic works of art for their acquired status as symbols of foreign oppression, rather than their intrinsic meaning as visual manifestations of the Catholic faith. On the other hand, if the rioters attacked these works of art for their intrinsic meaning, then the Beeldenstorm could be considered an act of iconoclasm in the truest sense of the word.

Attacking art

From medieval times to the modern day, people have had multiple reasons for attacking a work of art. But the gruesome deed itself doest not make someone an iconoclast; rather, it is the motivation behind the act.