4 literary masterpieces that make you despise the protagonist by the end

- Some unlikable book characters show their true colors from the beginning.

- Others initially appear sympathetic before taking readers down a dark and twisted path.

- Their transformations serve to illuminate the darker aspects of seemingly positive qualities, guiding readers along their intricate, often morally ambiguous paths.

Many of world literature’s most unlikable protagonists start unlikeable and end unlikeable. From the very beginning of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, it is clear that the titular Gray is a narcissist who’ll do anything to inflate his already monstrous ego. The same goes for Humbert Humbert from Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel Lolita, a pedophile with a silver tongue who conjures up excuses for his inexcusable actions.

But these characters form only the tip of the iceberg. A different yet equally interesting species of unlikable protagonist is the protagonist who starts off sympathetic but becomes more and more unsympathetic as the story develops. Though they appear similar, this type of character is not to be confused with other archetypes such as the tragic hero or antihero. The former (Oedipus, Hamlet) are good people who make bad decisions due to fate or circumstance, while antiheroes (Jack Sparrow, Batman) are morally ambiguous individuals who, in spite of their flaws, possess notable heroic qualities.

Each of these archetypes serves a distinct narrative purpose. Tragic heroes demonstrate that even the best of us can be brought low by unavoidable destiny. Antiheroes teach us, in the simplest of terms, that not all heroes wear capes. Protagonists who seem likable and then turn out unlikeable — let’s call them turncloaks for the sake of ease — can illuminate the dark side of seemingly positive qualities and characteristics. Because turncloaks deceptively win our support in the early chapters, we tend to follow them down whatever dark and twisted path they end up taking, even when we’d rather not. Below are five examples of such paths.

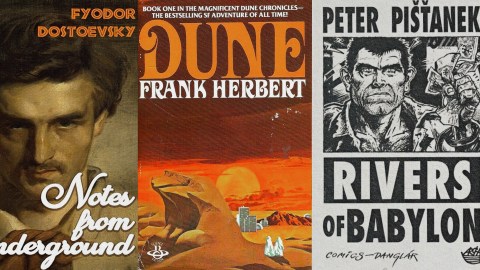

The Underground Man from Notes from Underground

The Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky had a knack for taking his characters on journeys that change them beyond recognition. The arrogant Rodion Raskolnikov we meet at the start of Crime and Punishment, for instance, is nothing like the repentant soul we find in the final passages. However, few Dostoevskian turncloaks are as compelling as the Underground Man, the protagonist of his 1864 novella Notes from Underground.

Written as a response to the utopian fiction that consumed Russia’s intelligentsia at the time, Notes from Underground is a mirror that reflects the ugliest, most pitiful aspects of humanity back at us. The Underground Man is a man torn apart by contradictions. He is incredibly proud, yet deeply insecure. He loathes his colleagues but also longs for their respect and acceptance. He is simultaneously convinced of his own worthlessness and angry with the world for failing to recognize his unlimited potential. He is quite possibly the most relatable character ever written.

At first, this relatability makes the otherwise insufferable Underground Man come across as comical, even endearing. It’s hard to read through sections where he overanalyzes his relations with a coworker, turning the tiniest interactions into an existential crisis, and not recognize a part of yourself in him. The same goes for a scene where he attends a party he both does and doesn’t want to be at. Sitting in a corner, sipping a drink, he alternates between judging others for not including them in their conversation and berating himself for wanting to be included in the first place. But as Notes from Underground progresses, his behavior turns from funny to pathetic to downright despicable. Giving credibility to the story’s opening lines, “I am a sick man…I am an angry man…I am an unattractive man,” the Underground Man, having been kicked out of the party, goes as far as to tell a young prostitute that she can come live with him, only to turn her away when she shows up at his doorstep.

Rácz from Rivers of Babylon

Rivers of Babylon, written in 1991 by the Slovak author Peter Pišťanek, tells the story of a young, simple-minded, and broad-shouldered ex-soldier called Rácz who leaves his impoverished village in the Slovakian countryside to work as the stoker of a hotel in Bratislava. There, he gradually gets caught up in the criminal underworld that hijacked the country’s privatization following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Rácz reluctantly accepts the job so he can earn the money he needs to marry his childhood love. Once in Bratislava, where he acquires a taste for money and power, his aspirations change. Instead of returning to the countryside, he becomes involved with and eventually establishes himself as the tyrannical boss of the illicit currency exchange business operating out of the hotel lobby. Forgetting all about his engagement, he starts dating a dancer who moonlights as a prostitute, then abandons her when she is no longer of use to him. He imprisons two immigrants in the hotel’s boiler room to do his dirty work for him. By the end of the novel, having become one of the most powerful mafia bosses in all of Slovakia, he sets his eyes on the mayorship of Bratislava. Pišťanek does not philosophize, but his message is clear: The big city did not “corrupt” Rácz so much as it brought out his true character.

Rácz has been interpreted as a foil to Vladimír Mečiar, a real-life politician who served as Slovakia’s prime minister between 1990 and 1998 and was heavily criticized for his autocratic tendencies, strongman persona, and ties to organized crime. Balkan Insight fittingly described Mečiar’s time in power as reading “like a cheap thriller” that saw Slovakia turn from just another Soviet satellite into a “black hole in the heart of Europe,” a description that would not feel out of place if printed on the jacket of Rivers of Babylon.

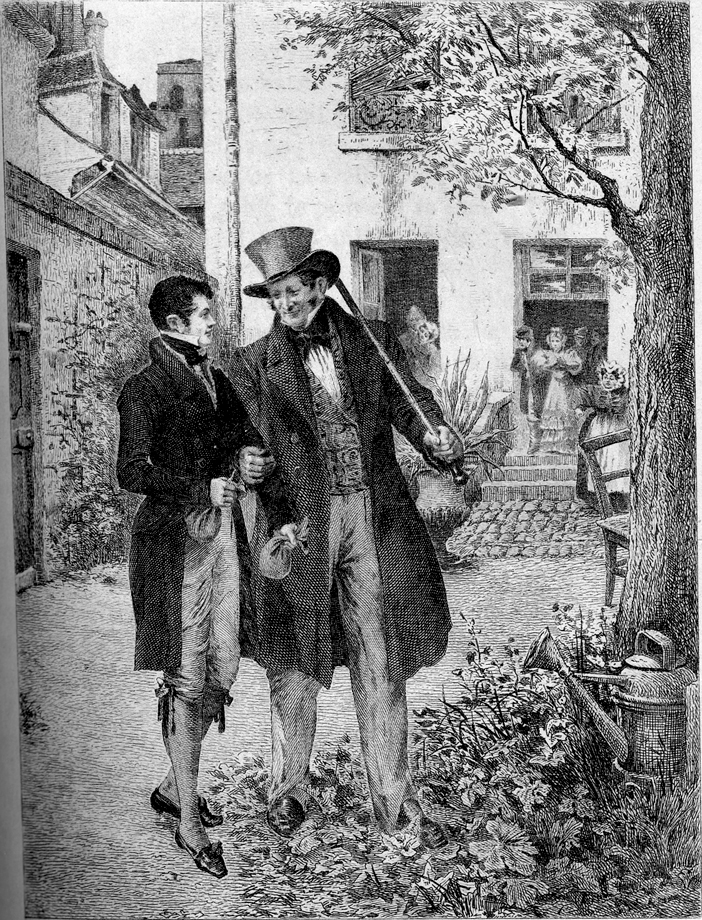

Eugène de Rastignac from Father Goriot

Eugène de Rastignac is a recurring character in La Comédie humaine, a series of interconnected novels and short stories by the French writer Honoré de Balzac that take place in and around post-revolutionary Paris. The protagonist of Father Goriot, Rastignac arrives in the capital a poor and sheltered nobleman eager to carve out a place for himself in high society.

But social mobility in this dog-eat-dog environment comes at a high price, one the benevolent Rastignac is initially unwilling to pay. Staying in an affordable boarding house, he nobly refuses an offer from one of its seedy residents — a con artist called Vautrin — to seduce an impressionable socialite, opting to rely instead on his own charisma. Throughout the Comédie humaine, Balzac contrasts Rastignac’s relatively principled personality to that of another climber, Lucien de Rubempré, who accepts Vautrin’s help only to suffer the consequences.

That’s not to say Rastignac is portrayed as a saintly figure. Far from it: Throughout Father Goriot, the nobleman learns that to get ahead, he too must compromise on his ideals. He does so by pursuing a relationship with Delphine, daughter of the titular Goriot, a successful vermicelli maker who forced himself into poverty after passing all of his hard-earned wealth into the hands of his spoiled, neglectful children. When the abandoned Goriot lies dying, it is Rastignac, not Delphine, who stays by his side and attends his funeral. Although Balzac casts Rastignac in a positive light, he concludes Father Goriot on a pessimistic note: with the protagonist turning his back on the old man’s grave and heading back into the city, into the arms of Delphine.

Paul Atreides from Dune

Frank Herbert’s science-fiction epic Dune tricks readers into thinking that its protagonist, Paul Atreides, is a straightforward hero: a ruse that is further reinforced by the casting of Timothée Chalamet in the recent film adaptation. But although Paul’s journey may follow the conventional “hero’s journey” story arc as outlined by Joseph Campbell, moving from life to death to rebirth, Paul is not the messianic figure the Fremen tribe of Arrakis believes him to be.

Upending age-old narrative traditions, Paul’s heroism takes a sinister turn when Herbert reveals that the Bene Gesserit, an Illuminati-like secretive order of psychic matriarchs, has long been conditioning the Fremen to expect the arrival of a messiah, or mahdi, in their native tongue.

Paul, similarly caught in the Bene Gesserit’s web, finds himself losing control of the religious order he was supposed to lead. As emperor of the galaxy, he is told he must follow the “Golden Path,” a potential future that, through countless sacrifices great and small, allegedly ensures the survival of mankind. Herbert never explains what the Path is supposed to save mankind from, and throughout the Dune books, he hints that other, less destructive paths could well lead to the same outcome. Ultimately, Paul’s ascension to the imperial throne is not the happily-ever-after ending that, say, Aragorn’s crowning represents in The Lord of the Rings. Instead, it’s an allegory to real-world history in which kings and prophets use religion as a means to justify their actions.