How the bizarre novel “Tristram Shandy” became an 18th century meme

- Tristram Shandy is filled with digressions, irrelevant observations, and parodies of literary tropes.

- The novel made its author, Laurence Sterne, famous. It became a “marketing phenomenon,” complete with branded merchandise.

- By breaking the rules of literature, Sterne created new opportunities for future writers like Virginia Woolf and James Joyce.

While there are many articles from mainstream publications that reintroduce the timeless works of Honoré de Balzac, Vladimir Nabokov, and Emily Brontë to contemporary audiences, one has to look far and wide to find a non-academic article that explores the legacy (and lunacy) of Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman.

This is a shame because, contrary to what its antiquated title would suggest, the novel is as insightful and entertaining as it is accessible. Notoriously resistant to categorization, Tristram Shandy can best be summarized as a botched attempt by its eponymous protagonist to relate the overly convoluted story of his fairly unremarkable life — a story that is constantly interrupted by unnecessary digressions, irrelevant observations, and other misplaced devices.

The novel’s unusual, humorous conceit turned Sterne — a hitherto unknown parish priest from Yorkshire with little to no writing experience — into a regional celebrity. “The first two volumes were wildly popular,” Judith Hawley, a scholar of 18th century English literature, told the BBC. “There was a lot of branded merchandise; race horses were named after him; lots of imitation novels. It became a marketing phenomenon.” Sterne himself is believed to have said: “I wrote not to be fed, but to be famous.”

His fame outlived him. The same BBC article goes on to tell how, when Sterne’s “freshly buried body” was stolen by graverobbers and sold to the anatomy department of the University of Cambridge, the students recognized the author and arranged for his reburial. Though Sterne was eventually forgotten by the general population, his unique writing style — a prototype of the stream of consciousness style we are familiar with today — went on to influence writers like Virginia Woolf and James Joyce.

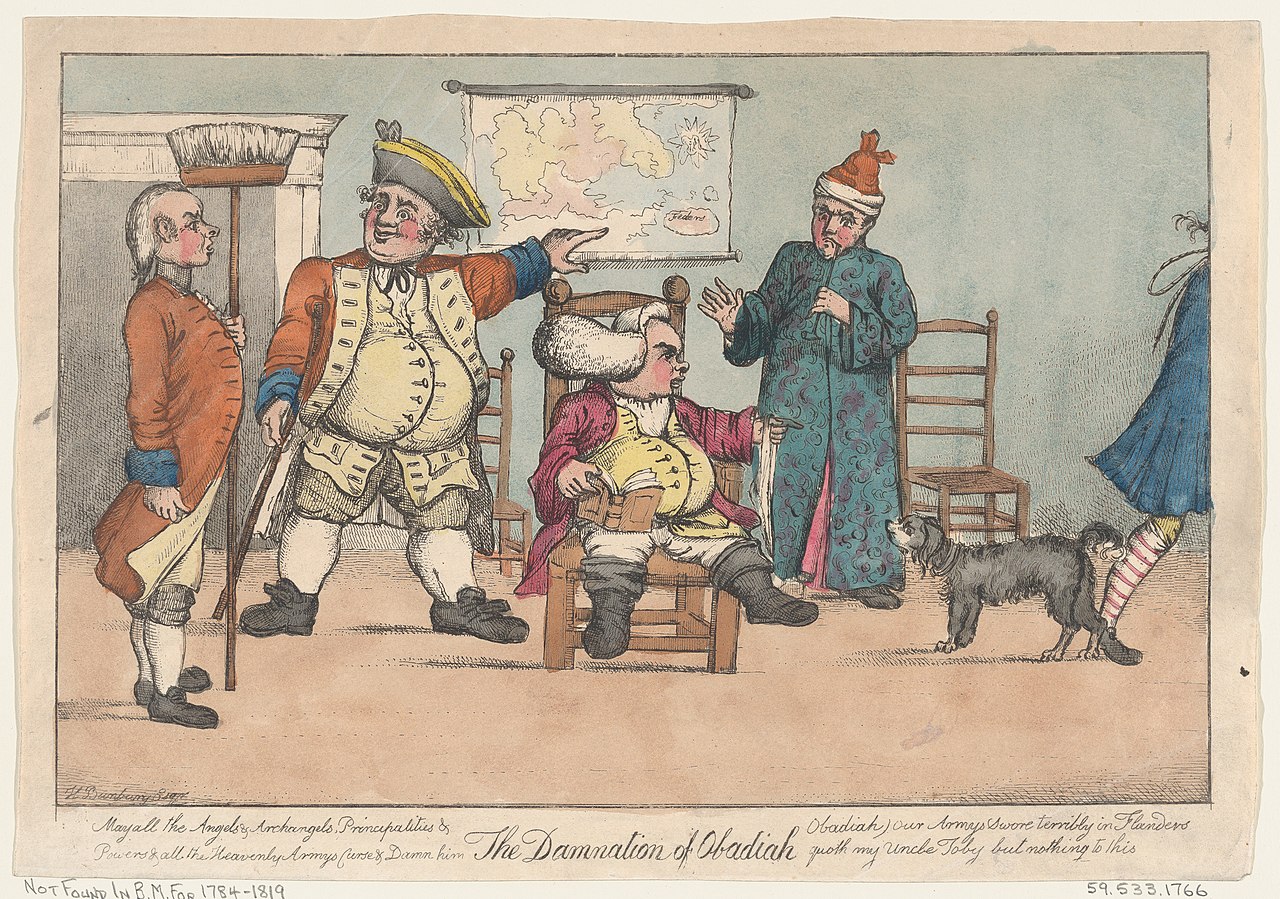

Contemporary readers who stumble upon Tristram Shandy are often shocked by the novel’s modern feel. Indeed, Sterne’s trademark irony and subversive use of literary tropes turn his work into the 18th century equivalent of a meme or “shitpost,” something Oxford Languages defines as “a deliberately provocative or off-topic comment posted on social media, typically in order to upset others or distract from the main conversation.” And this is but the tip of the Tristram Shandy-iceberg.

The novel and its form

The length and depth of the digressions seen in Tristram Shandy put procrastinating students and filibustering politicians to shame. Without giving away too much of the actual plot, Tristram — who, to reiterate, is supposed to be telling the history of his life — does not get to the event of his own birth until the novel’s third volume, hundreds of pages in. In the same volume, the author decides to present his belated preface because, “‘Tis the first time I have had a moment to spare.”

Initially, critics took these digressions at face value and argued that the story’s long-windedness was simply meant to show Tristram’s short attention span. In later years, readers caught on to the artistic and philosophical implications of Sterne’s irony. In 18th century Europe, novels weren’t just read for entertainment purposes; they were means through which writers perceived and analyzed reality. By ridiculing literary tropes, Sterne was calling the credibility of fiction into question.

One of the most interesting reviews of Tristram Shandy is that of Viktor Shklovsky, a Russian critic who rejected extra-textual information such as historical context or authorial biographies in favor of close readings. According to Shklovsky, the novel’s unconventional plotting does not indicate that the inexperienced Sterne was ignorant of literary conventions. On the contrary, his clearly calculated subversions demonstrate a deeply rooted understanding of those same conventions.

Tristram Shandy is often considered in the context of 18th century Romanticism, a movement in art and philosophy that rebelled against the ideas of the Enlightenment, favoring the power of emotion over that of reason. To verify this connection, one would have to compare Tristram Shandy to other Romantic novels of the same time period. Shklovsky, in his analysis, focuses exclusively on the novel’s form: its use of diction, syntax, structure, and voice. The way Shklovsky saw it, writes Kenneth E. Harper in “A Russian Critic and ‘Tristram Shandy’”:

“This was pre-eminently a novel of form and about form, and Sterne is everywhere a conscious innovator and experimenter. The structural ‘abnormalities’ are proof of the novelist’s preoccupation with formal devices. The apparent chaos is viewed not as the product of whimsy or eccentricity but as the result of a deliberate and rational plan.”

He goes on to write that Tristram Shandy “is as orderly and meaningful as a Picasso painting.”

In his review, Shklovsky wrote that Sterne was chiefly interested in “retarding the transposition of action.” Put another way, he was not interested in having a narrative that flowed effortlessly from chapter to chapter without any abrupt changes. Instead of inserting the familiar — and often tiresome — “separation scene” to bridge two different scenes, Sterne simply connected passages that had no logical relationship to another, creating a “braking” effect that ultimately served a similar purpose.

The legacy of Tristram Shandy

Sterne addresses his trope subversions in an aside. “Writers of my stamp have one principle in common with painters,” the novel reads. “Where an exact copying makes our pictures less striking, we choose the less evil; deeming it even more pardonable to trespass against truth, than beauty. –This is to be understood cum grano salis; but be it as it will, –as the parallel is made more for the sake of letting the apostrophe cool, than anything else.”

By breaking with literary conventions, Sterne broadens our conception of what a novel could look like. He also opens up new opportunities for future generations of writers. For example, prior to Tristram Shandy, many novels were written without regard for time duration. In Sterne’s novel, the very concept of narrative time is recognized and ridiculed, suggesting that stories need not necessarily unfold in the objective, chronological order of real life.

As an aside, Tristram Shandy serves as a perfect illustration of one of Viktor Shklovsky’s most well-known ideas about storytelling: estrangement. Estrangement is the act of describing a familiar object or routine in such a way so that the reader feels as though they were encountering this object or routine for the first time. In essence, Sterne’s literary subversions result in Tristram Shandy estranging the novel as an art form in its entirety.

Ironically for Shklovsky, neither the significance nor magnificence of Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy can be fully comprehended without considering the novel’s place in the history of literature. Although the novel is highly unconventional, it is also — for that exact reason — quintessentially conventional. “Those who deny that Tristram Shandy is a novel,” writes Harper, “will also deny that the symphony is music.” Adds Shklovsky, “Tristram Shandy is the most typical novel in world literature.”