Google’s Self-Driving Cars Are Ridiculously Safe

A few weeks ago, I attended a wedding just outside Richmond, Virginia, 100 miles from my home in Washington D.C., so I needed to rent a car for the weekend. There’s no feeling quite like getting back behind a steering wheel after time away from driving. It’s a liberating feeling, a taste of freedom, the ability to go anywhere. Wawas suddenly become accessible. Hamburgers taste better from the drive-thru. That ecstasy you feel is control; it’s a small bit of autonomy in a world where we too often feel like objects acted-on rather than autonomous actors.

It’s this sort of feeling that fuels many people’s anxiety (and, in some cases, enmity) toward the idea of self-driving cars. One example: That weekend trip to Richmond also reintroduced me to the cultural affliction that is sports talk radio. One of the topics on this sports show, curiously enough, was whether the hosts and their callers would feel comfortable in an autonomous vehicle. The overwhelming number of voices dripping from my speakers put on a top-notch demonstration of the Dunning-Kruger Effect, the cognitive bias wherein people who don’t know what they’re talking about assume their expertise on a subject is much higher than it is. The common refrain that afternoon was something akin to: “I wouldn’t feel safe trusting my life to a computer.”

While that’s an understandable take — remember all that talk above about freedom and autonomy? — such reasoning leads to a dead end when you consider our current bevy of empirical evidence. Consider the sterling track record of their fleet of automated prototypes, most of which have the ability to switch between human driver and computer driver. Google spokeswoman Jacquelyn Miller (via Cyrus Farivar of Ars Technica) recently made the following announcement regarding her company’s fleet of self-driving death machines:

“We just got rear-ended again yesterday while stopped at a stoplight in Mountain View. That’s two incidents just in the last week where a driver rear-ended us while we were completely stopped at a light! So that brings the tally to 13 minor fender-benders in more than 1.8 million miles of autonomous and manual driving — and still, not once was the self-driving car the cause of the accident.”

Farivar’s piece focuses mostly on Google’s announcement that they’ve updated their self-driving car site with accident reports after calls for more transparency. At this point, they’re just logs for whenever someone rear-ends the car. Several of Farivar’s commenters aptly note that the accident referenced above likely would not have happened had both cars been self-driving.

At some point, this technology will become so advanced that lawmakers will be forced to debate whether or not to outlaw manual driving, according to Tesla CEO Elon Musk. There’s an argument for it: Deaths and injuries from auto accidents are bad. They would decrease drastically if human error were to cease to be a liability. Plus, you can’t drive drunk if you can’t actually drive. The counterargument against this perspective, outside of the rah-rah “freedom” appeals, would necessarily center on security. Could hackers take control of your car while it’s on the road?

It’s important to nudge Google and other self-driving carmakers toward transparency. The evidence at the moment indicates the technology is moving along nicely, but that doesn’t mean we ought to do away with our steering wheels quite yet.

It’s as important to shed preconceived notions of what driving means to us, because despite the great feeling I get when I’m in control, I have to be aware that I’m always one human error away from causing myself or someone else great bodily harm. That’s why we have to be prepared to be unselfish if this technology improves to a level where a switch to full automation (at least on public roads) is in the best interest of society.

If you don’t know much about autonomous cars, but want to learn, Brad Templeton goes over all the basics in the video below:

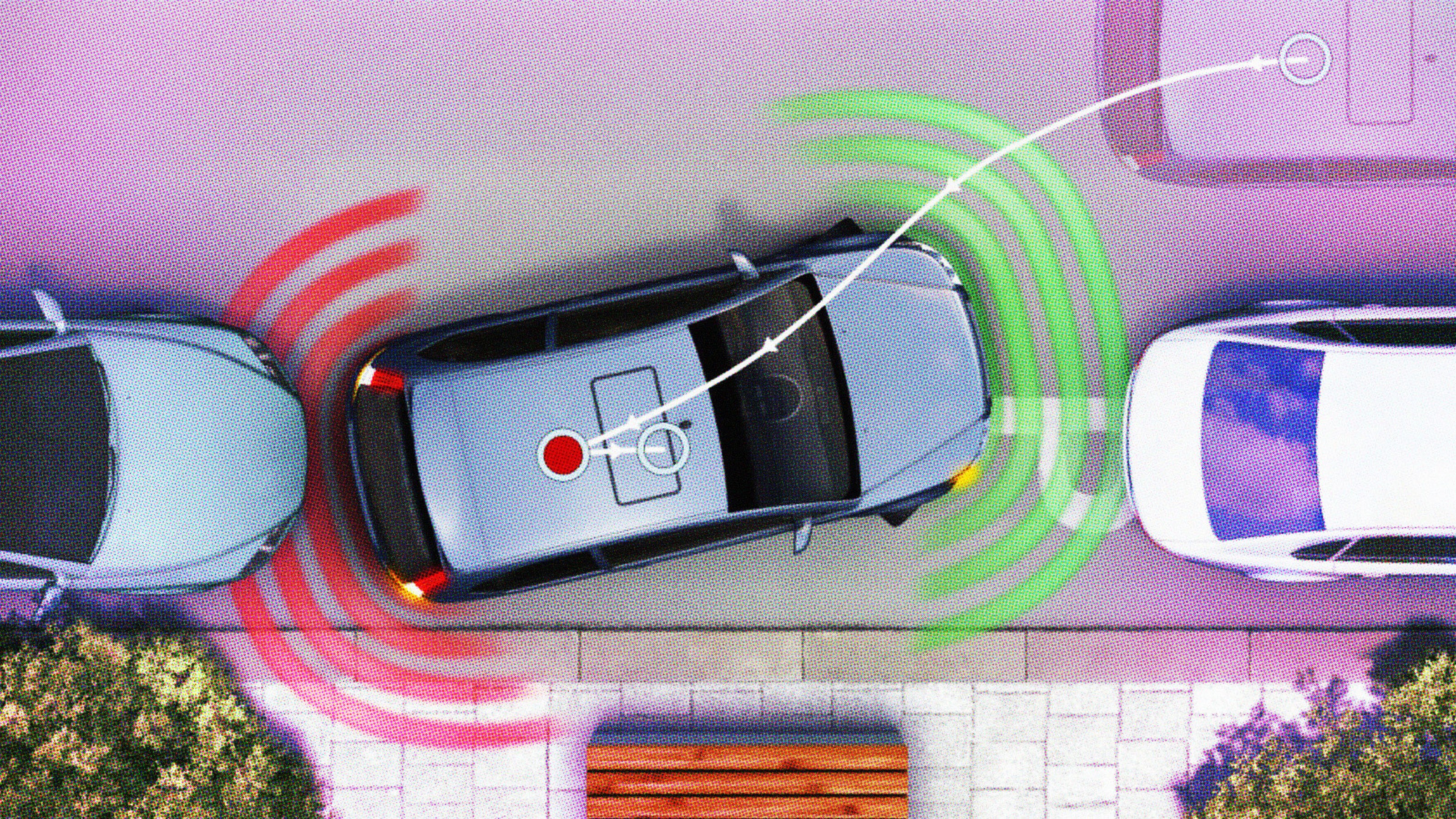

Photo credit: GLENN CHAPMAN/AFP/Getty Images