Acid rain: Real danger or overhyped doomsaying?

- Decades ago, scientists warned that acid rain could be catastrophic for the environment.

- Since then, some have argued that the worry was overblown and unnecessary.

- There’s no question that acid rain was a problem, even if the degree of damage is open to debate.

Thirty-five years ago, the waters of Lake Colden in New York’s Adirondack Mountains were found to be too acidic to support fish, making the picturesque, high-altitude body of water one of the signature casualties of acid rain. Red spruce trees in New England were also showing signs of strain as the rain leached vital calcium from the soil, severely stunting the trees’ growth. Today, Lake Colden’s trout have returned and the spruce trees are flourishing, tangible signs that the decades-long effort to mitigate acid rain has worked.

Now that sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide emissions — the causes of acid rain — are greatly reduced in Europe and North America, a success based on capstone environmental legislation, it’s easy to look back on the panicked news stories from the 1980s and 1990s and wonder if acid rain was really more of a “nuisance, not a catastrophe,” as William Reville, an emeritus professor of Biochemistry, wrote for the Irish Times. Seeing as how we dealt with the problem, we may never conclusively know the answer.

What we do know is that scientists in the U.S. and Scandinavia originally discovered acid rain in the 1960s and chose to gather evidence for years — more than a decade in some cases — before sounding the alarm in the 1970s and 1980s. American ecologist Gene Likens and his colleagues found that while rainwater was often slightly acidic, with a pH of 5.6, by 1980 the average rainfall in the U.S. was at a pH level of 4.6, about ten times more acidic! And it was getting worse.

In areas downwind of coal power plants — the primary sources of sulfur dioxide emissions — the problem was even more acute. The pH of individual rainstorms sometimes dropped to 3 or below, similar to that of grapefruit juice or soda. These sorts of downpours weathered buildings, dissolved nutrients in the ground that trees need to survive, and caused aluminum to be released in the soil.

Across the Atlantic Ocean in Sweden, scientists warned that half of the country’s lakes and rivers would reach a critical pH level by the early-mid 21st century and cause mass fish die-offs if actions weren’t taken to stop acid rain.

Whether these scenarios constitute “hype,” a “nuisance,” or a “catastrophe” might depend on one’s feelings towards scientific predictions, the environment, and wildlife, but there was no question that acid rain was a growing problem, and one that humans were responsible for.

There was no question that acid rain was a growing problem, and one that humans were responsible for.

That’s why, after years of public debate and amendments to the Clean Air Act in 1990, legislators in the U.S. instituted a bipartisan cap and trade program that capped sulfur dioxide emissions in the power industry at a drastically lower level compared to 1980 and allowed companies to either lower their emissions or buy and trade credits from companies that did. Limits were also placed on nitrogen oxide emissions.

The free-market program was a resounding success. The national average of sulfur dioxide annual ambient concentrations in the U.S. decreased a whopping 93% between 1980 and 2018.

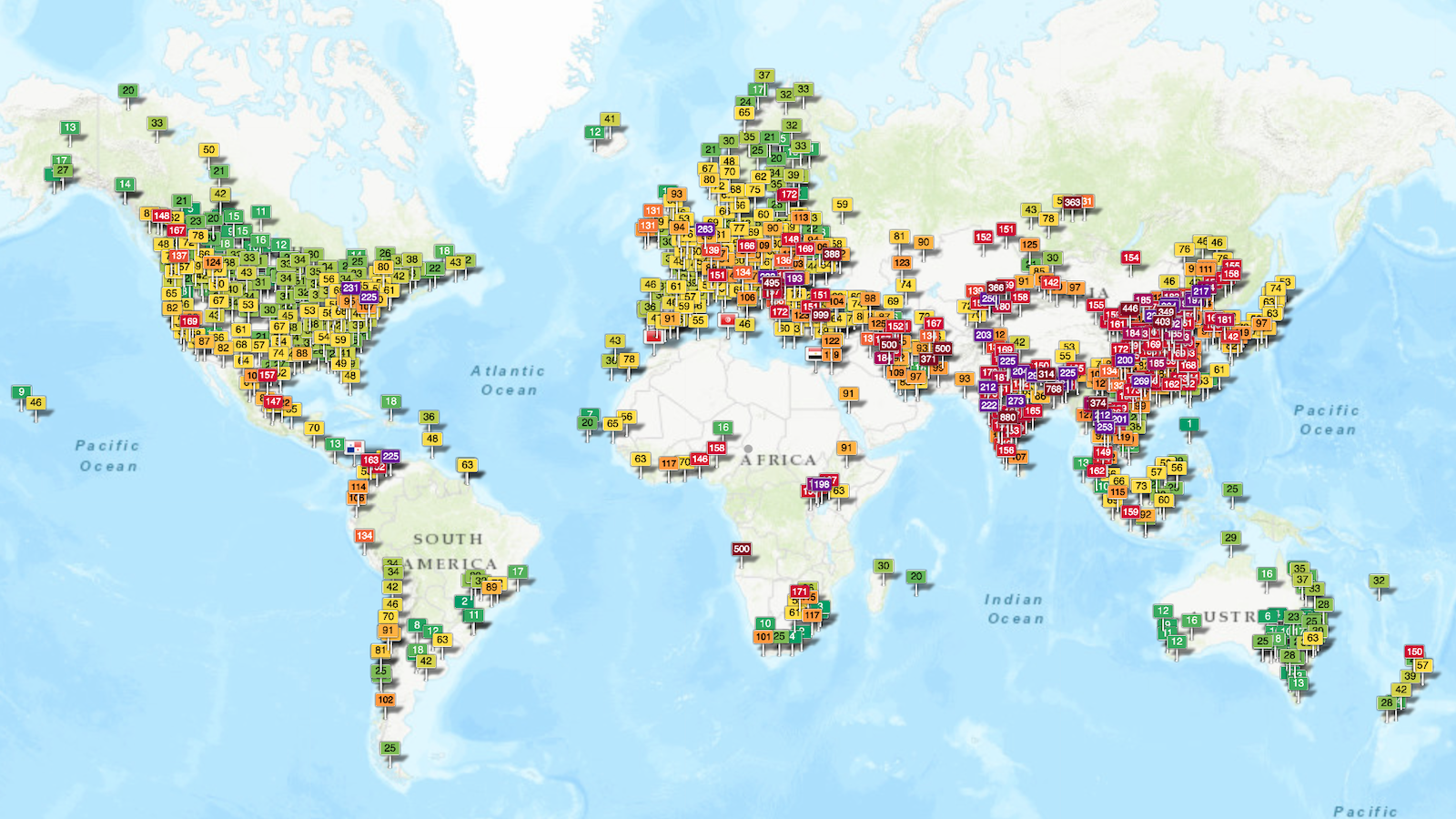

But while the cloud of acid rain has all but vanished from much of Europe, North America, Australia, and Japan, it is a surging problem in places like India and China, where coal power is still widely used. Urbanizing areas of Latin America and Africa are also seeing precipitation grow increasingly acidified.

For these places, reducing noxious emissions that fuel acid rain is a tandem goal with lowering air pollution as a whole. Four million people die prematurely due to outdoor air pollution globally. Making air more breathable and rain less acidic benefits everyone, regardless of whether or not acid rain is a hyped problem or a genuine one.

This article was originally published on RealClearScience. It was written by Ross Pomeroy, a regular contributor to Big Think.