Cats learn the names of their feline friends

- Dogs are well-known for learning a handful of human words. But what about cats?

- Scientists explored this by using a test called “visual-auditory expectancy violation,” which measures how confused an animal behaves when it sees something unexpected.

- The results suggest that cats do indeed know the names of the other cats they live with.

Names are powerful. They make the strange familiar, the unknown known. Learning that names are associated with specific objects demands a considerable amount of practice. Babies, for instance, require up to a year of listening to conversations before they learn to associate the name “daddy” or “mommy” with a specific person. As it turns out, our furry friends can do this, too.

In 2021, scientists who study animal communication (known formally as zoosemiotics) discovered that some “gifted word learner” dogs associate objects and words at a similar level as infants. Of course, we might expect this of a dog, ever the people-pleaser. But what about cats, which have a reputation for being blasé about human affairs?

Saho Takagi, a research fellow at Azabu University, was suspicious of cats’ seeming indifference. “I want people to know the truth. Felines do not appear to listen to people’s conversations, but as a matter of fact, they do,” she said in a recent interview with The Asahi Shimbun.

Cats know more than they let on

Takagi’s wariness was warranted. According to previous research, cats understand human communication better than their reputation suggests. Like dogs, they can use human pointing and gaze to find food. They even can discriminate between human facial expressions and attentional states, according to a 2016 study titled “Cats Beg for Food from the Human Who Looks at and Calls to Them.”

However, feline perception is far more keen than discerning body language. Another study showed that cats can distinguish their human-assigned name from the names of their feline friends (that is, those that live in the same household). Furthermore, they can distinguish names from general nouns, such as “table” or “chair.”

To Takagi and her colleagues, these studies suggested that cats are eavesdropping on our conversations, learning from human speech. The researchers believed it was possible that cats weren’t merely recognizing the names of other cats, but that they were learning what the names correspond to. In other words, it’s one thing to recognize the series of grunts coming from the hairless ape that feeds you, but it is another thing entirely to know that the ape is talking about your friend.

The researchers hypothesized that cats learned to associate names with other cats by observing interactions between their owners and their feline friends.

How to confuse a cat

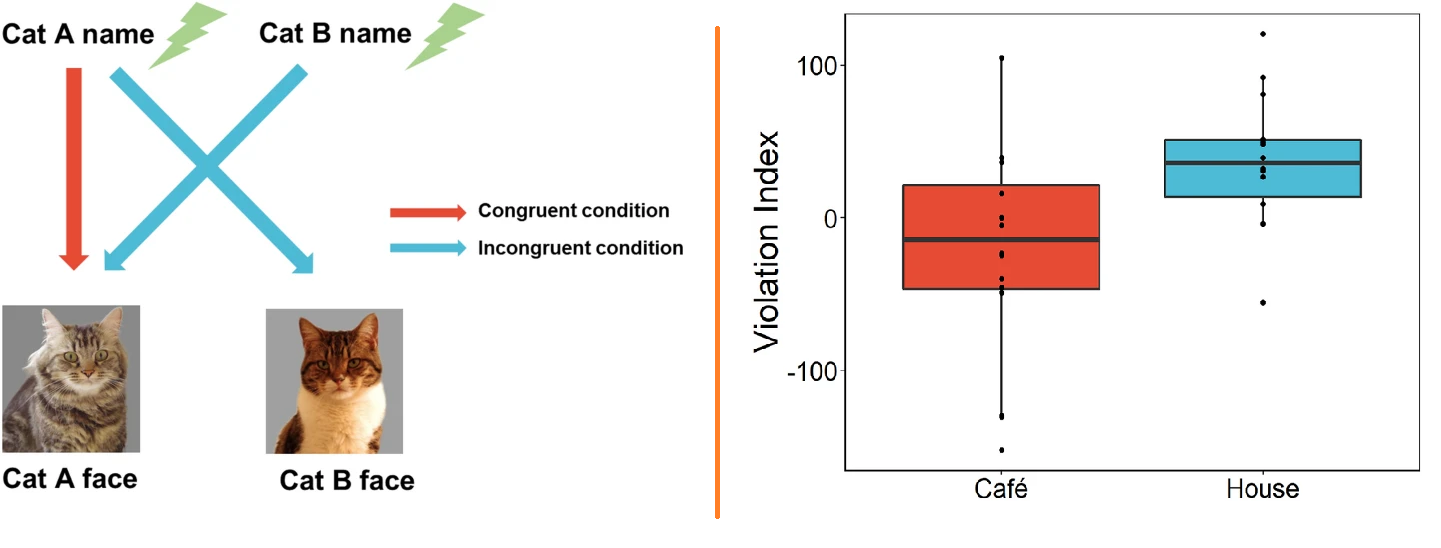

In a recently published study, Takagi and her colleagues explored this hypothesis. They compared two groups of cats: one group consisted of household cats that lived with at least two other cats; the other consisted of cats that lived in “cat cafés,” which had up to 30 cats that visitors could freely interact with. The researchers assumed household cats are more likely to observe a consistent, specific name for a cohabitating cat, whereas café cats would observe a single cat called a variety of names.

They determined whether cats linked human words (cat names) with their corresponding objects (other cats) using a simple, two-phase test called visual-auditory expectancy violation. During the name phase, the study participant was softly restrained by a scientist in front of a laptop computer. When the participant was calm and oriented toward the monitor, the researcher played a recording of its owner saying the name of one of its kitty companions.

Immediately after the name phase, the face phase began. The researcher released the cat, and a cat’s face appeared on the monitor. Sometimes, the cat that appeared on the screen matched the name spoken; other times the name and the image did not match, which would trigger a visual-auditory expectancy violation.

When animals experience the expectation violation, they investigate by staring or sniffing suspiciously at the monitor. The researchers converted this behavior into a violation index (VI). The greater the VI, the longer a cat investigated the monitor when the name and image did not align. House cats had a significantly greater VI than café cats. This indicates that only household cats anticipated a specific cat’s face upon hearing the cat’s name, suggesting that they know the names of their cat friends.

“This is the first evidence that domestic cats link human utterances and their social referents through every day experiences,” write the authors of the study. “However, we could not identify the mechanism of learning. It is still an open question how cats learn the other cats’ names and faces.”