Even cats probably find “cat people” disturbing

- There are a few best practices for interacting with cats, including allowing them to decide when to be pet, refraining from picking them up, and generally touching them less.

- In a new study, researchers found that people who rate themselves as more knowledgeable about cats were no more likely to follow these best practices, and actually were slightly more likely to pet cats in ways they generally find unpleasant.

- It’s possible that cat peoples’ cats actually love all that extra attention they’re getting, but it’s more likely that cat people are blinded by their affection for their furry friends.

Whether earned or unearned, there’s a general stereotype in Western societies that “cat people” — you know, the ones who really like cats — are weird and even a little unsettling. A recent study published in the journal Scientific Reports hints that cats might feel the same way.

In research published last year, Dr. Lauren Finka, a feline welfare and behavior scientist at Cats Protection and a Visiting Fellow at Nottingham Trent University, characterized how to interact with our feline friends in ways that they actually enjoy. Allowing cats to decide when to be pet, refraining from picking them up, generally touching them less, and — if they show interest in being touched – focusing on the base of their ears, cheeks, and under the chin while avoiding the belly and root of the tail, are a few best practices.

Do touch, don’t touch

Finka, along with nine other UK-based colleagues, have now followed up that study with another, trying to ascertain whether people actually follow this advice. Paradoxically, they discovered that people who rate themselves as more knowledgeable of and experienced with cats are more likely than others professing less experience to disregard the best practices. “Cat people” don’t follow cat rules.

Finka and her colleagues recruited 119 participants to complete a personality assessment and answer questions about their experiences with cats. Subjects were then invited into a laboratory setting and filmed as they interacted with three different adult cats previously screened for friendliness. Each session lasted five minutes.

“Participants were instructed to quietly enter the cats’ pen and to sit in the corner nearest to the entrance…” Finka and her colleagues described. “Participants were encouraged to interact with the cat as they normally would, with the exception of picking them up. Participants were also asked to remain in their seated position for the duration of the test, which effectively enabled cats to avoid human-interactions if they desired.”

The researchers reviewed and scored all of the individual participants’ feline interactions based upon the aforementioned best practices, then checked how those scores lined up with subjects’ survey responses. “The best predictor of ‘best practice’ scores was number of years living with cats,” the researchers found. That certainly makes sense; people who spend more time with felines should be more accustomed to their behavior.

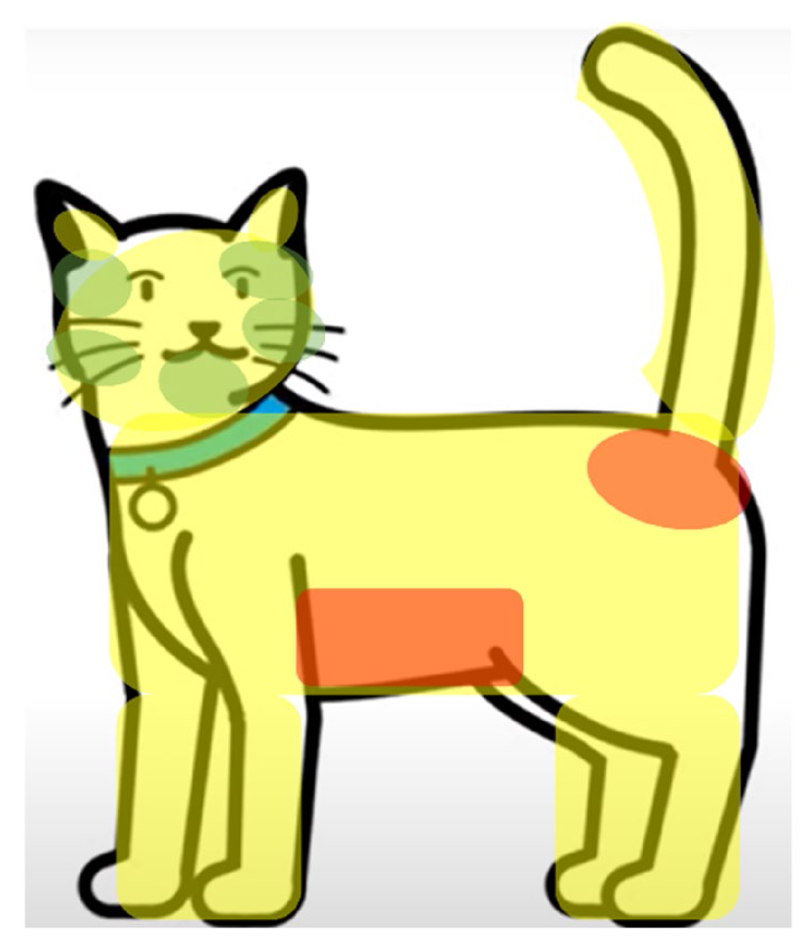

However, participants who rated themselves as more experienced and knowledgeable (a.k.a., “cat people”) were no more likely to follow best practices than others. In fact, they were more likely to be overly touchy, petting cats a lot more in both their favored (green) areas but also slightly more often in their disliked (red) areas.

“The lack of positive relationships between ‘best practice’ handling styles, ownership experiences, and self-evaluations of knowledge appears consistent with previous literature in domestic dogs, where similar variables were not strongly associated with increased animal empathy or more accurate interpretations of dog behavior,” the authors noted.

Cat people

Moreover, lending further credence to the “wacky, older cat person” stereotype, Finka and her colleagues also found that people aged 56 to 75 and those who scored higher in neuroticism were more likely to hold and restrain felines in the sessions, something that most cats absolutely do not enjoy.

“Of course, every cat is an individual and many will have specific preferences for how they prefer to be interacted with,” the researchers said in a statement.

So, it’s possible that cat peoples’ cats actually love all that extra attention they’re getting. Their affectionate owners almost certainly think so.