Chimpanzees understand the difference between malice and inability

- Humans judge behavior not only by outcome but by motivation or intent.

- Chimpanzees can do the same thing. Notably, they can tell when a human is unable to give them a treat that they want.

- However, in this particular experiment, chimps do not seem to grasp the concept of knowledge or ignorance.

“It’s the thought that counts.” We’ve all said it, and we’ve all heard it. The proverbial phrase lets others know that we appreciate their efforts, and it gives voice to a quintessentially human trait: the ability to consider the context of another’s actions when deciding whether or not they treated us fairly.

The response is so ingrained in our societies that it shows up in the fabric of our legal system. We tend to punish people less severely for a crime committed by accident than we punish those who deliberately sought to do harm.

These traits are indispensable to humans because we live in and depend on collective groups of peers. It remains unclear whether other social animals, such as chimpanzees, possess the same cognitive ability to distinguish ignorance from choice when evaluating social actions.

In two recent studies published in the journal Biology Letters, a research group led by Dr. Jan Engelmann at UC Berkeley investigated which variables chimpanzees consider when evaluating social behavior. The researchers wondered: When reacting to the outcome of a social interaction, did chimpanzees consider whether their peers did the best they could, given the circumstances?

According to Engelman and his colleagues, the answer is “probably.” The researchers found that chimps did not fuss when offered sub-par help if it was the only option. In this way, chimps act like humans and evaluate the situational context of an action before passing judgment on how they were treated. Questions remain, however, concerning how much reasoning chimps use in more muddled social contexts, when the line between altruism and malice is not clearly defined.

Evaluating freedom of choice

When evaluating an action, we all inadvertently consider freedom of choice. Did our friends choose to be an hour late because it was easier, or were they stuck in unpredictable traffic? According to researchers, two main factors lead individuals to act outside of their choice — constraint and ignorance.

In constrained action, someone is aware of an alternative but cannot pursue that path due to physical psychology or social constraint. Our hypothetical friends cannot, for example, start driving on the side of the highway. They would be breaking social rules and would receive a hefty fine. On the other hand, sometimes we act against our own wishes because we are ignorant that another option exists. In the case of traffic, maybe our friends did not realize there was an alternative route.

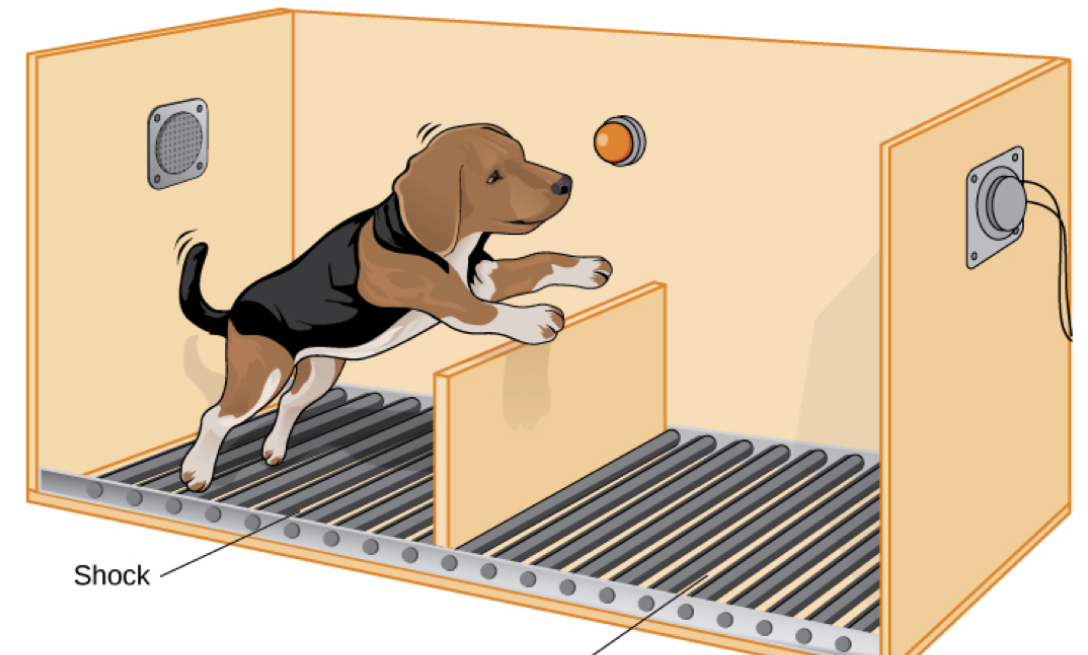

Engelmann and her colleagues wanted to know whether chimpanzees also consider freedom of choice when evaluating actions. The researchers crafted a social interaction to study this. First, researchers loaned chimpanzees a tool. When the subject returned the tool, a human would give them some food. Before the experiment, the researchers determined the preferred food choice of each subject. In the experiment, the chimps could see two types of food on display — their favorite treat or a different, less tasty snack.

In every case, the researchers did the opposite of what the chimps wanted: they gave them the non-preferred food. However, researchers manipulated the social history behind this outcome by creating experimental situations where humans either chose to give the chimps mediocre food, or were apparently forced to because of constraint or ignorance.

How chimpanzees judge a social interaction

In the first experiment, researchers displayed two food items to a chimp, one of which was the individual chimp’s preferred food choice. However, the preferred food was locked in a box. In half of the trials, the researchers showed the chimps that they could open the box, yet they only offered the other non-preferred food item. In the other half, the researchers created a situation of constraint: the experimenters demonstrated that they could not open the locked box and then offered the non-preferred food item to the hungry chimps.

Chimpanzees who believed the experimenter had no choice but to give them the less desirable food were more likely to return the tool and accept the food without any aggression. Essentially, they realized that the researcher tried to help, failed, and offered the next best option. On the other hand, when experimenters deliberately chose not to share the better food, the chimps behaved aggressively, spitting at the experimenter and physically posturing to demonstrate their dissatisfaction.

Do you get where I’m coming from?

In the second experiment, a researcher hid the preferred food somewhere the chimp could see it. In half of the trials, the researcher offering food could not see the chimp’s favorite snack and therefore did not realize it was available. In another group, researchers demonstrated to the chimps that the human did know where the hidden snack was. In neither case did the chimps receive what they wanted.

This time, the chimps were less forgiving. In both situations, the chimpanzees behaved aggressively and were less likely to trade the tool when they perceived that the researchers were holding out. It seemed that the less forgiving chimpanzees probably could not understand that in some cases, the humans only offered sub-par food out of ignorance, not malice.

The pair of experiments revealed that chimpanzees do not judge a social interaction solely on its outcome — what type of food they received. They also considered the context of the situation. However, they only considered freedom of choice when it was constrained physically, not when it was limited by lack of knowledge. This puzzled the researchers, since chimpanzees have been shown to understand the knowledge of their peers in the past. The extent to which chimps can evaluate the behavior of others based on their knowledge or personal desires remains unanswered.

So, to all the experimenters who got spit on by seemingly ungrateful chimps, remember: they might have tried their best to be empathetic, given the circumstances.