Eyes painted on cow butts thwart lion attacks

Image source: Ben Yexly/UNSW

- Lions help maintain balance in their ecosystems, but they also kill cattle.

- The big cats are ambush predators who depend on the element of surprise.

- In an experiment, eyes painted on cow backsides appear to deter lions from attacking.

For cattle-owning subsistence farmers in Botswana, lions pose a threat to the livestock on which they depend. Attempts to keep cattle safe often result in the shooting or poisoning of the big cats. Aside from the obvious moral discussion of what makes the life of one animal more worthy of preservation than another, large predators play a vital role in preventing trophic cascades in which the loss of one species throws an entire ecosystem dangerously out of balance. The African lion population is in decline, with the estimated number of adults ranging from 23,000 to 39,000, as opposed to more than 100,000 lions in the 1990s.

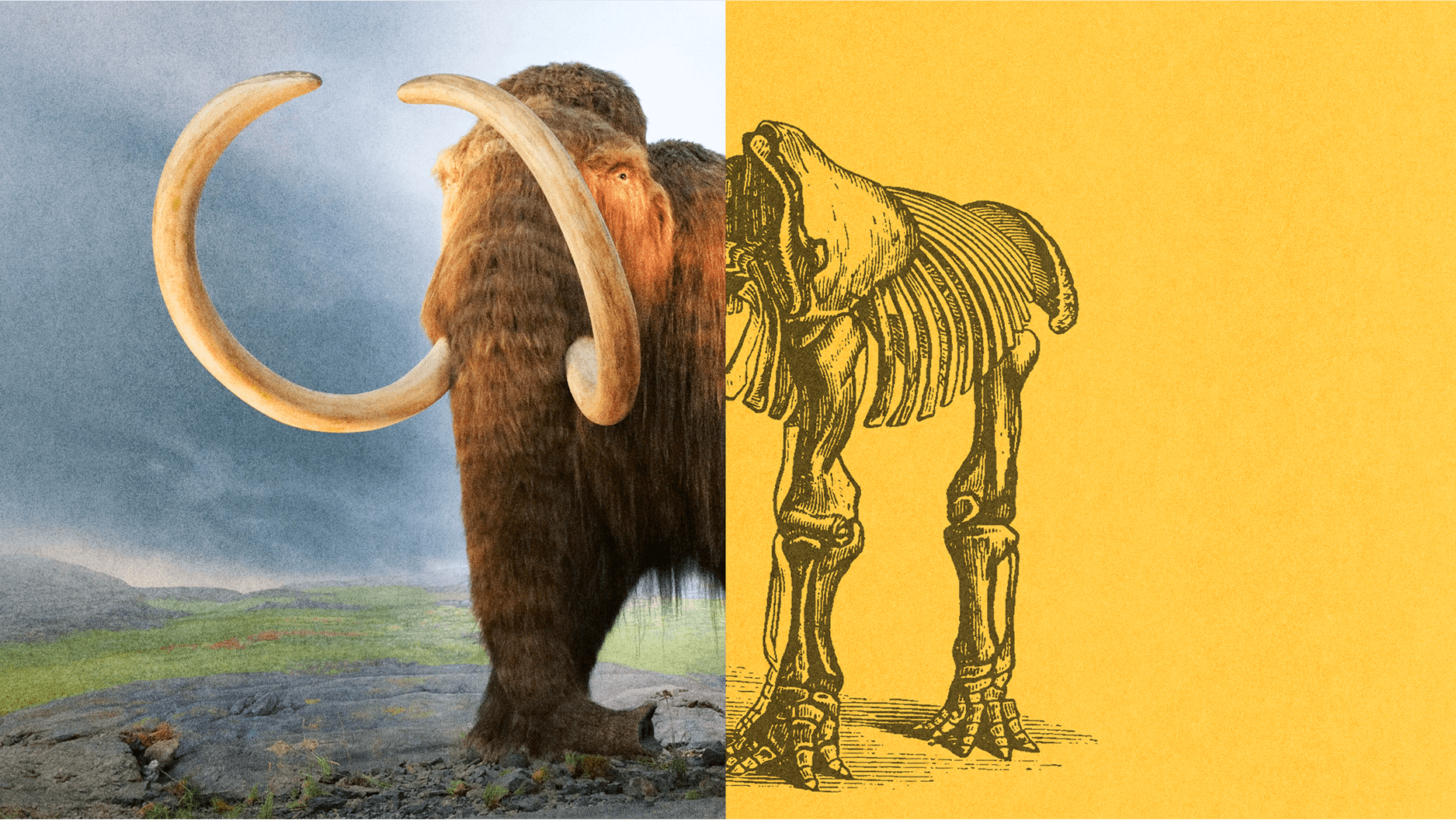

As part of the search for a non-lethal remedy to the farmers’ problem, a collaboration between the Botswana Predator Conservation Trust (BPCT) in Africa and the Centre for Ecosystem Science at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), and Taronga Conservation Society, both in Australia, recently completed a program they called the “i-cow project.” Its tongue in cheek [pun intended] moniker might just as easily be spelled “eye-cow,” since what it involved was painting large eyes on cows’ hind quarters to see if they might deter lion attacks. They did.

Image source: Bobby-Jo Photography/The Conversation

Lions are ambush predators who sneak up on their quarry. Ambush predators are common in nature, on land and sea and in the air. They come in all sizes, from the praying mantis to the orca, and what they have in common is a sit (or swim)-wait-pounce strategy.

The element of surprise is a critical part of an ambush predator’s method, and previous research on lion and leopard behavior in Africa’s Okavango Delta suggested that an attack may be called off when an ambush predator believes it’s lost the element of surprise.

Conservation biologist Neil Jordan of UNSW’s Centre for Ecosystem Science has seen this in action. He tells UNSW Newsroom about how he got the idea for i-cows as he was watching a lion about to attack an impala near a village in Botswana where he was staying. “Lions are ambush hunters, so they creep up on their prey, get close and jump on them unseen. But in this case, the impala noticed the lion. And when the lion realized it had been spotted, it gave up on the hunt.”

There’s also support for this deterrent effect in nature, where having markings that look like eyes staring back at a predator appears to provide a distinct evolutionary survival advantage for a range of species, including butterflies, moths, reptiles, fish, and birds.

No mammals, however, have eyespots, and the i-cow team believes this is the first time that humans have investigated the effect of adding eye markings to them.

Prepping a cowImage source: Bobby-Jo Photography/The Conversation

Jordan and his colleagues painted markings on cattle from 14 herds. 683 cows had eyes painted on their rumps, a cross was painted on the posteriors of 543 cows to learn if a natural eye shape was required to deter predators, and 835 cows were left unpainted.

Most lion attacks occur during that day — cattle are more likely to be securely penned at night — so the test cattle were painted in the morning and released to forage as usual. There were 49 painting sessions with each lasting for 24 days.

While 15 of the unpainted cows were ultimately taken by lions, not a single eye-painted cow was killed. Unexpectedly, a painted cross seemed to help a bit, if not as much as an eye painting — only 4 cross-painted cattle were attacked.

The researchers point out a couple of potential issues with their research.

First, the presence of completely unmarked cows in their experiments may have provided a more obvious target for lions in that they had no potentially off-putting (or even confusing in the case of the crosses) markings.

Second, animals learn. It may be that the area’s lions would eventually habituate to or figure out the humans’ subterfuge. The researchers note in an article for The Conversation noting that this tends to be a problem with non-lethal anti-predator remedies in general.