One of the world’s most inbred animals lives in Death Valley

- The Devils Hole pupfish lives in one of the most extreme, isolated environments in the world — a sweltering, 200-square-foot, water-filled cavern on the outskirts of Death Valley.

- The tiny fish’s resilience and underdog character have won the hearts of conservationists, who keep close tabs on the population.

- They have defied the odds for millennia, but new research shows the pupfish face yet another threat — severe inbreeding at a level never seen before.

Death Valley derives its fame from extremes. The 3.3 million acre-park is among the hottest and driest places in the world. Yet the park is not so one-dimensional — it has much more depth to it than you may think.

A vast network of water systems snakes below the surface of Death Valley, taking shape as a warren of subterranean caverns and lakes. When rain or snowmelt percolate through the ground, water enters an aquifer and eventually pools in the underground waterway. The process is slow. It takes approximately 10,000 years for a single molecule of water to reach these caverns from the surface, according to the National Park Service.

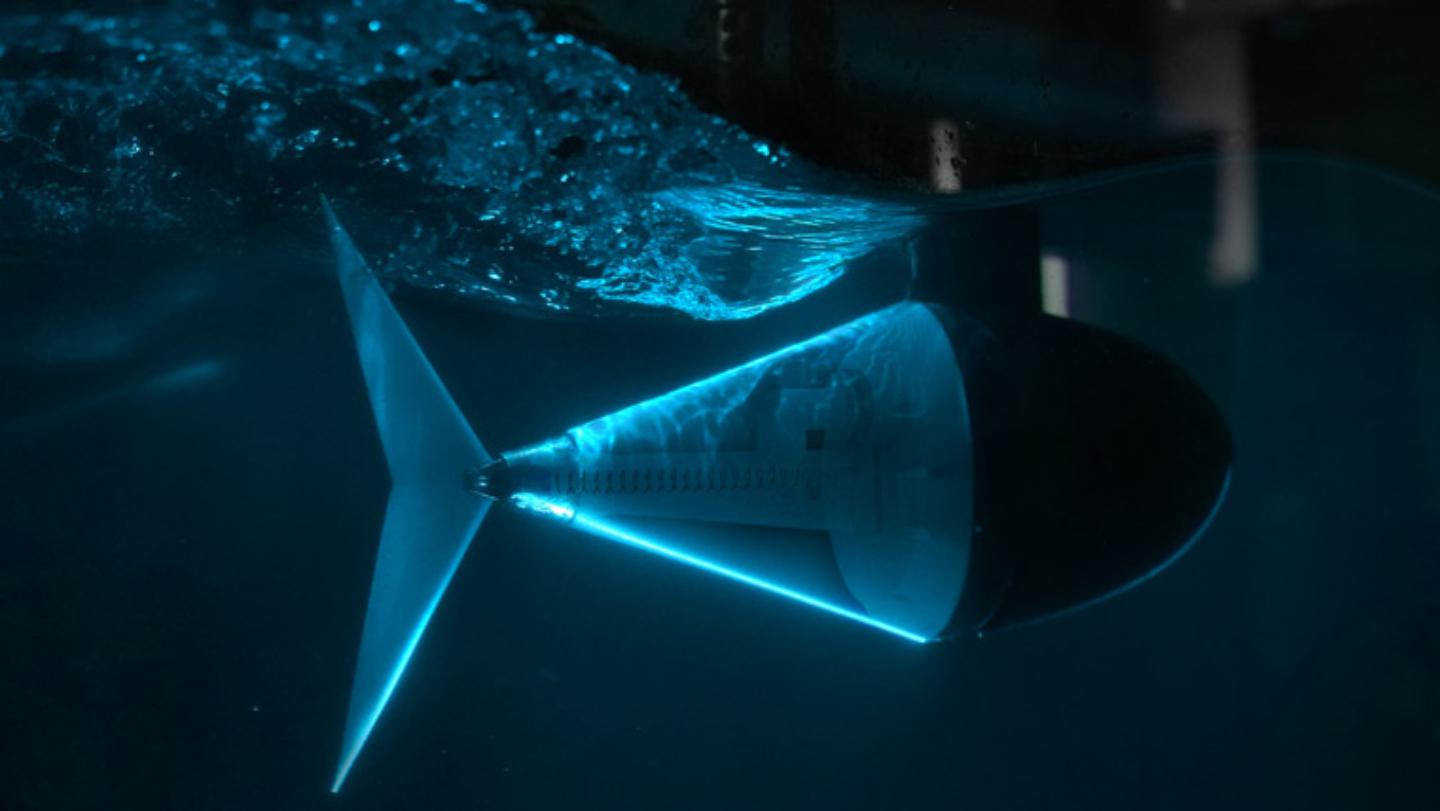

The entrance to this abyss is called Devils Hole, and the name fits the place. Go to this part of Death Valley, and you will encounter a hole in the Earth with water hot enough for the devil himself. The narrow passageway drops into cavernous, seemingly unreachable depths. Divers have explored as low as 500 feet below the surface, and they still have not hit the bottom.

A tiny underwater world

Despite its great depths, many biologists focus their attention on the first 80 feet of Devils Hole, where a compact shelf of shallower water lies. Here, the Devils Hole pupfish (Cyprinodon diabolis) makes its home. Its 10-by-20-foot area (3-by-6 meters) gives it the smallest known range of any vertebrate species.

Along with cramped quarters, this part of Devils Hole presents other challenges to aquatic organisms. It holds a nearly constant temperature of 34° C (93° F), and it gets no direct sunlight during the winter (limiting the growth of algae, which the pupfish eat). For most fish, living in a pitch-black hot tub would already be intolerable. Add in the poor concentration of dissolved oxygen, which would be lethal to many underwater organisms, and you can see why the Devils Hole pupfish does not need to worry about anyone else moving in.

In fact, you will not find the Devils Hole pupfish anywhere else. The 30 known species of pupfish, so named for their playful, puppy-like movements, share a general ability to withstand harsh living conditions. But even among this rugged group, the Devils Hole pupfish takes extreme lifestyle to a new level. Their mere existence is tantamount to a miracle. In 2013, their numbers plummeted to just 35 individuals. Today, the number of Devils Hole pupfish individuals hovers around 263, the highest recorded population in 19 years.

There are a lot of reasons why this pupfish may be doomed: Climate change, habitat decline, lower water levels, and human activity all threaten this isolated population. But we have never really been confident that the Devils Hole pupfish would stick around. Scientists and policymakers chose to list the species as endangered in 1967, almost immediately after the Endangered Species Act — at the time called the Endangered Species Preservation Act — took effect.

Many empathize with the pupfish as an underdog who was slated to lose but kept fighting. You may have even heard of them on the famed podcast Criminal, which documented the public outlash that resulted when a few people unwittingly partied a little too hard near Devils Hole. People really care about these fish.

A shallow genetic pool

Now, new research has identified another obstacle to their survival — incest.

The isolation of Devils Hole makes finding a new mate challenging. It’s a bit like constantly bumping into your ex at the store, if your ex was also your cousin. Earlier this month, scientists reported results in Proceedings of the Royal Society from a genetic analysis done on the Devils Hole pupfish. The researchers found that the species’ sequences are 58 percent identical on average, which is “the equivalent of five to six generations of full sibling matings,” according to Christopher Martin, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, and co-author of the paper. The researchers estimate that the Devils Hole Pupfish is the most inbred species in the world.

In this study, the researchers sequenced the entire genome of eight Devils Hole Pupfish, and one preserved specimen from the 1980s. They also sequenced genomes of related species in surrounding areas.

Specimens from the 1980s helped the researchers determine that the population was highly inbred even prior to population bottlenecks in 2013 and 2017. This finding suggests that the pupfish has a history of repeated population contractions. Unsurprisingly, the Devils Hole pupfish harbor significantly greater mutational load than any of the other desert pupfish in the study.

Pupfish mutations

The researchers found some serious deleterious genetic mutations. For example, the eight specimens had mutations in a gene associated with sperm morphology. This makes it surprising that the fish can reproduce at all. They also found five genetic deletions associated with hypoxia, or low oxygen conditions. Changes to these genes are not surprising, given that Devils Hole is a highly hypoxic environment.

Paradoxically, though, the deletions suggest that the Devils Hole pupfish could be poorly equipped to physiologically deal with the stress of a low-oxygen environment. This might explain why they tend not to reproduce as successfully as other pupfish.

The authors caution that it would be rash to immediately start managing for these deleterious variants. First we need to link these genetic changes to decreases in survival or reproduction.

The study suggests that the Devil’s Hole pupfish remains in severe danger. Climate change will add to the peril by shortening the seasonal period where conditions are optimal for hatching on the shallow shelf where the Devils Hole pupfish spawns. Because environmental stress tends to exacerbate the problems created by inbreeding, we know the Devils Hole pupfish faces interacting threats that make survival a tougher prospect. Like many of the other threats predicted to wipe out these thumb-sized creatures, it seems like the Devils Hole pupfish has taken their genetic situation in stride. No one can ignore how their population has continued to grow.

We might even be able to help. Integrating genome sampling with conservation efforts is a new and promising scientific enterprise. Once we link a mutation to a change in survival or fecundity, we can monitor that gene closely and spot mutations as they occur. This foresight gives scientists a better chance to try using captive breeding programs to improve genetic diversity before populations plummet beyond recoverable levels.

That is the crux of endangered species management — you have to stop a species crossing that finish line. There is no turning back once a species goes extinct.