- A new species of “pumpkin toadlet” is discovered skittering along the forest floor in Brazil.

- It’s highly poisonous and brightly colored, and some if its bones glow under UV light.

- An analysis of the toadlets’ chirp song helped scientists establish that it’s something new.

It’s tiny, just a little bigger than a thumbnail. It’s partially fluorescent. It’s orange. And it’s very poisonous.

Led by herpetologist Ivan Nunes, scientists have reported in the journal PLOS ONE the discovery of a new “pumpkin toadlet” species of the genus Brachycephalus. Found in the Mantiqueira mountain range along Brazil’s Atlantic coast, it joins 35 other Brachycephalus species. The newcomer’s official name is Brachycephalus rotenbergae, named after Brazilian conservationist Elise Laura K. Rotenberg.

Distinguishing one Brachycephalus species from another isn’t straightforward, as there’s no telltale identifying mark. Instead, a more holistic profile has to be developed to tell one species from another.

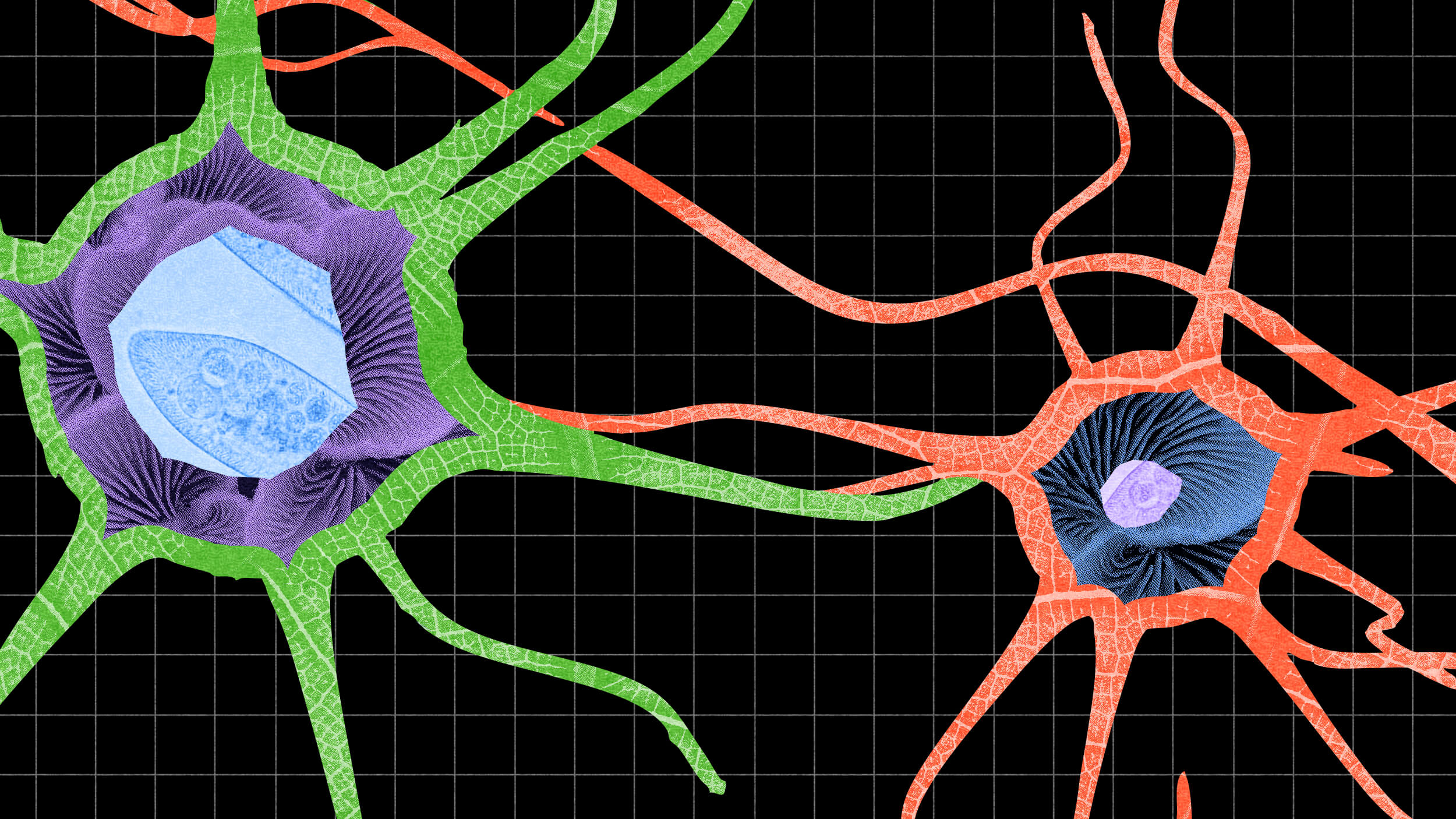

In this case, scientists considered the toad’s genes, natural history, gross anatomy (including its skeletal structure), and even its songs. Brachycephalus toadlets emit what’s considered an “advertisement call” — as in “Hey, I’m here!” — consisting of long sequences of chirps.

A find on the forest floor

Between October 2017 and September 2019, 76 field surveys were conducted in Brazil’s Atlantic forests as researchers studied B. rotenbergae, whose turf is the forest floor in the São Francisco Xavier Government Protected Area. Among the new species’ distinguishing features are a rounded snout and dark spots on its head. Additionally, it’s a bit smaller than its similar-looking cousin B. ephippium, and its chirps are not quite like those of any other Brazilian pumpkin toadlet.

Glow-in-the-dark bones

When B. rotenbergae is exposed to UV light, some of the bones just underneath their skin emit a green glow. “There’s an idea,” Nunes tells Smithsonian Magazine, “that fluorescence acts as signals for potential mates, to signal to rival males or some other biological role.”

As for the brilliant orange color, it may be one of nature’s warnings, a “don’t eat me” signal of extreme toxicity. Indeed, other Brachycephalus toadlets have tetrodoxins in their skin, and the researchers suspect this toadlet does, too. (Pufferfish and blue-ringed octopi also carry tetrodoxins.) Ingestion of these neurotoxins can cause a number of progressively nasty things, from a pins-and-needles sensation to convulsions, heart attacks, and even death.

Currently, there is neither an indication that the species is endangered, nor is it especially rare. The only concern the researchers have for the species’ survival is the growing population of wild boars in the area. The boars are tearing up the habitat of B. rotenbergae, rooting around for tasty seeds, nuts, acorns, and roots.

However, accidentally gobbling up a toadlet probably would be bad news for the boar.