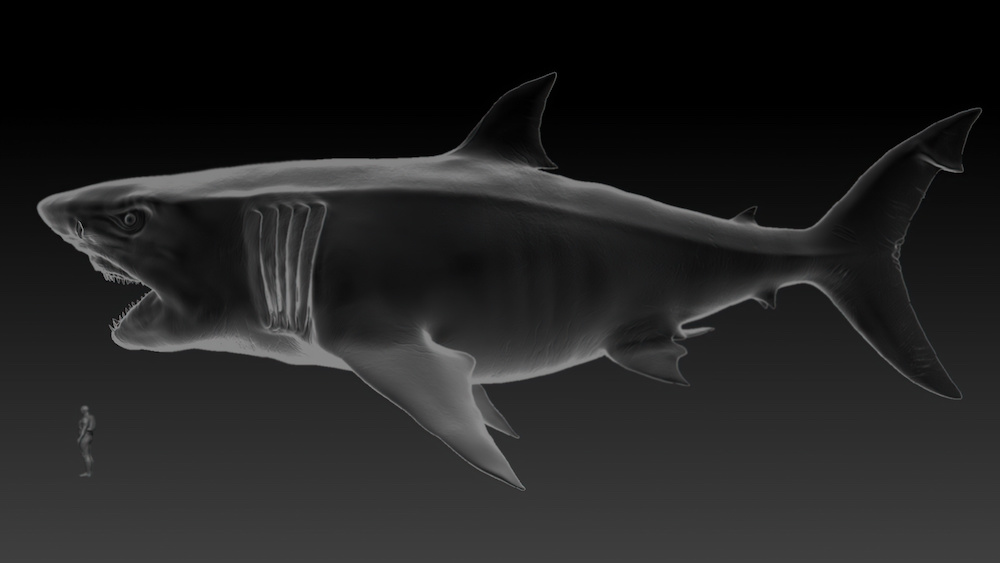

The great white shark has surprising dining habits

Photo by Gerald Schömbs / Unsplash

- A University of Sydney research team found that the great white shark spends an unexpectedly large amount of time feeding close to the sea bed.

- The group examined the contents in the stomachs of 40 juvenile white sharks and found the remains of a variety of fish species that typically inhabit the sea floor or are buried in the sand.

- The scientists hope that the information gained from this research will assist conservation and management efforts for the species.

In the first-ever study detailing the eating habits of great white sharks, researchers found that the predator spends an unexpectedly large amount of time feeding close to the sea bed.

black shark in blue waterPhoto by Gerald Schömbs on Unsplash

A research team from the University of Sydney looked at sharks off the east coast of Australia and found that in their stomachs were remains from a variety of fish species that typically inhabit the sea floor or are buried in the sand. Specifically, the group examined the contents in the stomachs of 40 juvenile white sharks, scientifically known as Carcharodon carcharias, who were caught in the NSW Shark Meshing Program.

“This indicates the sharks must spend a good portion of their time foraging just above the seabed,” explained lead author Richard Grainger, a Ph.D. candidate at the Charles Perkins Centre and School of Life and Environmental Sciences at the University of Sydney, in a press release. “The stereotype of a shark’s dorsal fin above the surface as it hunts is probably not a very accurate picture.”

The study was published on June 8, World Oceans Day, in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science. It’s an important step forward for scientists trying to better understand the great white’s diet and migratory behavior.

“We discovered that although mid-water fish, especially eastern Australian salmon, were the predominant prey for juvenile white sharks in NSW, stomach contents highlighted that these sharks also feed at or near the seabed,” said Vic Peddemors, Ph.D., a co-author from the NSW Department of Primary Industries (Fisheries).

The research team compared this new dietary information with published data on great white feeding habits from other parts of the world where the sharks make home, mostly South Africa. From there they were able to establish a nutritional framework for the species.

According to the research, the juvenile great white sharks’ diets relied primarily on pelagic — mid-water ocean swimming — fish, such as Australian salmon. This made up 32.2 percent of the shark’s diet. Bottom-dwelling fish like stargazers, sole or flathead made up 17.4 percent; batoid fish such as stingrays 14.9 percent; and reef fish, like eastern blue gropers, 5 percent.

The remaining species eaten by the sharks were unidentified fish or less abundant prey. Grainger pointed out that other marine mammals, sharks, and cephalopods — squid and cuttlefish — were eaten at lower rates.

“The hunting of bigger prey, including other sharks and marine mammals such as dolphins, is not likely to happen until the sharks reach about 2.2 meters in length,” Grainger said.

Another discovery was that bigger sharks tended to have diets that were higher in fat. Similarly to other animals, this is likely an adaptation to their higher energy needs for migration. Great white’s migrate seasonally along Australia’s east coast, traveling from southern Queensland to northern Tasmania. The range of distance covered increases with age.

“This fits with a lot of other research we’ve done showing that wild animals, including predators, select diets precisely balanced to meet their nutrient needs,” said co-author Professor David Raubenheimer, Chair of Nutritional Ecology in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences.

Great White Shark | National Geographicwww.youtube.com

Ultimately, the scientists hope that the information gained from this research will assist conservation and management efforts for the sharks, who are considered a vulnerable and declining species due to overfishing and accidental catching in gill nets.

Of particular interest to scientists is better management of relations between humans and great whites. According to National Geographic, of the over 100 annual shark attacks that happen worldwide, a whopping one-third to half can be attributed to great whites. Yet, research has found that the sharks, who tend to have a curious disposition, are often just taking sample nibble before releasing their human prey. So, at least we know humans aren’t a great white delicacy.