Invasion biology: Why intelligent alien life is not the biggest threat from space

- A recent paper suggests that the threat of interplanetary biocontamination is one to take more seriously.

- The authors propose using existing quarantine systems to take care of returning spacecraft and samples.

- The odds of any living organism traveling between worlds is low, but not zero.

Imagine one day a satellite falls back to Earth carrying something it didn’t leave with: a microscopic stowaway unlike anything life on Earth has ever encountered. After realizing that Earth can supply it with everything it needs, it rapidly begins a search for the best possible environment to multiply in and food to eat, which could be anything from the bloodstream of the dominant species on the planet to plastics.

This scenario — the plot of The Andromeda Strain by Michael Crichton — reflects a fear that likely dates back, in some form, to the ending of The War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells: that the effects of biological contamination are the real danger in space travel, far more dangerous than the threat of, say, flying saucers.

In a paper recently published in Bioscience, Anthony Ricciardi, of McGill University, and his coauthors discuss the risk of planetary cross contamination. The paper details how the risks of interplanetary cross-contamination don’t just run one way, and how we might come to better understand and handle the problem.

Invasion biology

The authors point to a new interdisciplinary field of study known as invasion biology as a guide to understanding the problems facing us as we begin to venture out into the cosmos with plans to bring objects home with us. It focuses on what happens when an organism moves beyond the area it evolved in and then works forward.

The field, while new, has some interesting ideas about how “invasions” of this kind might play out. For example, it proposes that:

- Insulated environments (e.g., islands, lakes, remote habitats) would be the most at risk of disruption if an alien organism is introduced.

- It is difficult to predict the results of any “invasion” like this.

- Treating it as a disaster that demands a quick response would be the best strategy.

But, what would an extraterrestrial “biological invasion” look like?

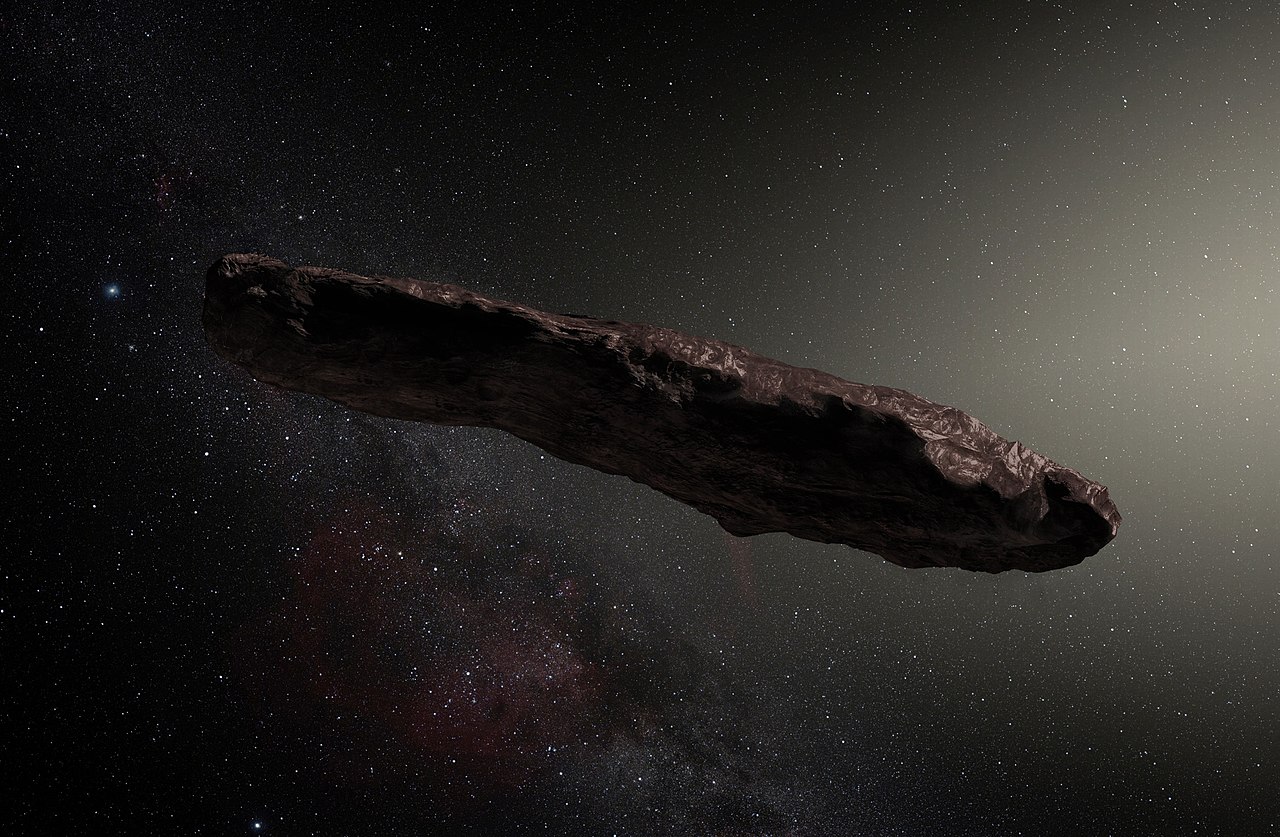

First on most people’s minds is the problem of some kind of space germ getting back here after, perhaps, hitching a ride on rock samples collected from the surface of another world. Such a thing, called forward contamination, could be disastrous if the introduced organism makes its way into an environment where it can thrive.

But this effect could go both ways. In 2019, the Israeli lunar lander Beresheet crashed on the Moon with cargo that contained, among other things, dormant tardigrades. Tardigrades, also known as “water bears,” are tiny organisms that are able to endure extremely inhospitable conditions, including the vacuum of space. While their arrival on the Moon was caused by an accident, the risk of such accidents can never be lowered to zero.

Now, imagine that happening but on Mars, where there is still some discussion about the ability of bacterial life forms to survive under its surface, or on Europa, whose subterranean sea may be home to multiple forms of life. The effects of an invasive species from Earth could be catastrophic on these alien ecosystems.

Avoiding cross-contamination

Luckily, concerns about biohazards in space have existed for decades and were considered in the 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies. One clause of that treaty instructs parties to “be guided by the principle of cooperation and mutual assistance and… conduct exploration of them so as to avoid their harmful contamination and also adverse changes in the environment of the Earth resulting from the introduction of extraterrestrial matter and, where necessary, shall adopt appropriate measures for this purpose.”

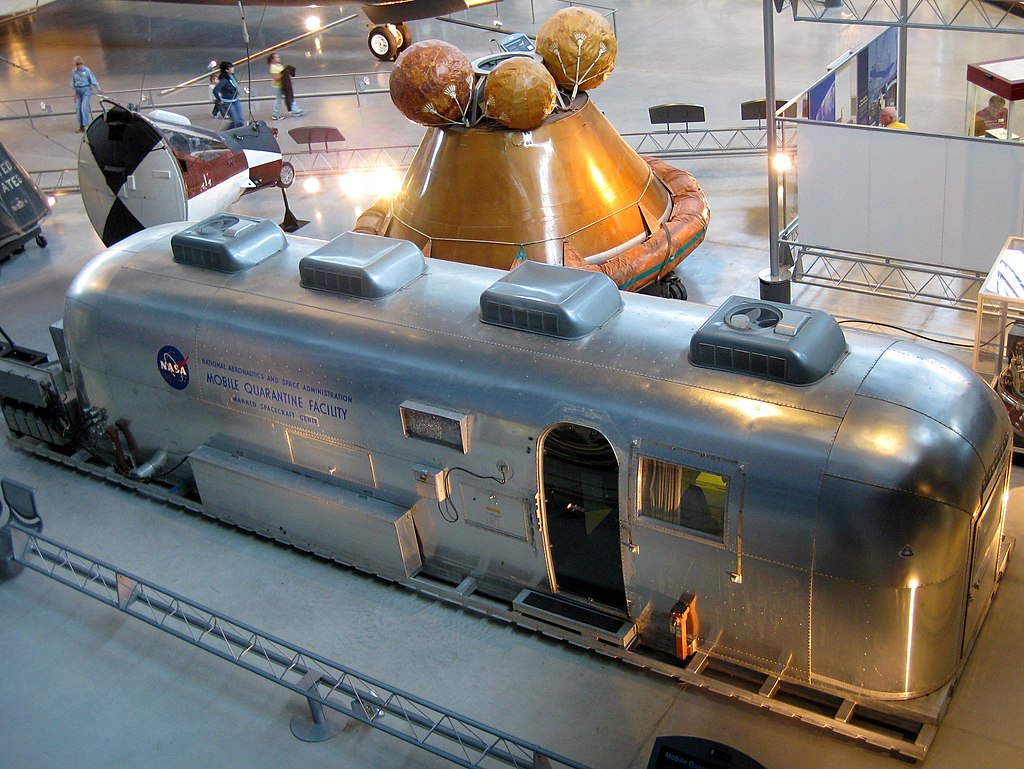

Space agencies have adopted precautions since that was signed. The Apollo 11 astronauts famously were unable to enjoy a cake prepared for their return to Earth because they had to quarantine in a specially built trailer. NASA was so concerned about the possibility of “Moon germs” that the trailer had a lower pressure than the building around it — to ensure that air, and any bacteria, would flow into the trailer rather than out of it.

It has been proposed that we know a bit more about biohazard control than we did in 1969, though there is room for doubt. The authors of the paper suggest that “protocols for early detection, hazard assessment, rapid response, and containment procedures currently employed for invasive species on Earth could be adapted for dealing with potential extraterrestrial contaminants.”

And before you worry too much about an invasion of little green microorganisms, the odds of any contamination of this kind are thought to be very low, because the distances and extreme conditions of the travel from one astronomical body to another are likely to kill off most stowaways. But “very low” isn’t zero: The authors suggest that, as space travel becomes more common, our standards for biological security should be improved.

So, while the problem of keeping contaminants away from Earth and any place we decide to travel to in the near future is being addressed, there is more we can do to keep everything where it belongs. Until tickets to Europa start going on sale, you don’t have too much to worry about.

Maybe wash your hands extra long after a trip to space to be safe, though.