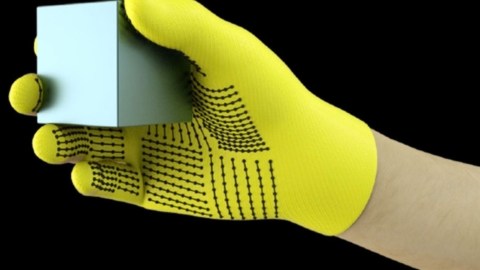

New MIT-developed glove teaches A.I.-based robots to ‘identify’ everyday objects

Image source: MIT

- MIT-affiliated researchers develop a hypersensitive glove that can capture the way in which we handle objects.

- The data captured by the glove can be “learned” by a neural net.

- Smart tactile interaction will be invaluable when A.I.-based robots start to interact with objects — and us.

Our hands are amazing things. For sighted people, it may be surprising how good they are at recognizing objects by feel alone, though the vision-impaired know perfectly well how informative hands can be. In looking to a future in which A.I.-based robotic agents become fully adept at interacting with the physical world — including with us — scientists are investigating new ways to teach machines to perceive the world around them.

This said, researchers from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have hit upon a cool approach: Tactile gloves that can collect data for A.I. — similar to how our hands feel. It could be invaluable to designers of robots, prosthetics, and result in safer robot interaction with humans.

Subramanian Sundaram, the lead author of the paper, which was published in Natureon May 29,says, “Humans can identify and handle objects well because we have tactile feedback. As we touch objects, we feel around and realize what they are. Robots don’t have that rich feedback. We’ve always wanted robots to do what humans can do, like doing the dishes or other chores. If you want robots to do these things, they must be able to manipulate objects really well.”

Image source: MIT

The STAG

The “scalable tactile glove,” or “STAG,” that the CSAIL scientists are using for data-gathering contains 550 tiny pressure sensors. These track and capture how hands interact with objects as they touch, move, pick up, put down, drop, and feel them. The resulting data is fed into a convolutional neural network for learning. So far, the team has taught their system to recognize 26 everyday objects — among them a soda can, pair of scissors, tennis ball, spoon, pen, and mug — with an impressive 76 percent accuracy rate. The STAG system can also accurately predict object’s weights plus or minus 60 grams.

There are other tactile gloves available, but the CSAIL gloves are different. While other versions tend to be very expensive — costing in the thousands of dollars — these are made from just $10 worth of readily available materials. In addition, other gloves typically sport a mingy 50 sensors, and are thus not nearly as sensitive or informative as this glove.

The STAG is laminated with electrically conductive polymer that perceives changes in resistance as pressure is applied to an object. Woven into the glove are conductive threads that overlap, producing comparative deltas that allow pairs of them to serve as pressure sensors. When the wearer touches an object, the glove picks up each point of contact as a pressure point.

Image source: Jackie Niam/Shutterstock

Touching stuff

An external circuit creates “tactile maps” of pressure points, brief videos that depict each contact point as a dot sized according to the amount of pressure applied. The 26 objects assessed so far were mapped out to some 135,000 video frames that show dots growing and shrinking at different points on the hand. That raw dataset had to be massaged in a few ways for optimal recognition by the neural network. (A separate dataset of around 11,600 frames was developed for weight prediction.)

In addition to capturing pressure information, the researchers also measured the manner in which a hand’s joints interact while handling an object. Certain relationships turn out to be predictable: When someone engages the middle joint of their index finger, for example, they seldom use their thumb. On the other hand (no pun intended), using the index and middle-fingertips always means that the thumb will be involved. “We quantifiably show for the first time,” says Sundaram, “that if I’m using one part of my hand, how likely I am to use another part of my hand.”

Feelings

The type of convolutional neural network that learned the team’s tactile maps is typically used for classifying images, and it’s able to associate patterns with specific objects so long as it has adequate data regarding the many ways in which an object may be handled.

The hope is that the insights gathered by the CSAIL researchers’ STAG can eventually be conveyed to sensors on robot joints, allowing them to touch and feel much as we do. The result? You’ll be able to vigorously shake hands with an automaton without getting your hand crushed.