Blocking a single gene awakens same-sex behavior in male fruit flies

- Same-sex sexual behavior is incredibly common. It has been observed in about 1,500 species.

- The biological mechanism underpinning the behavior remains elusive.

- Now, researchers have identified a gene that prevents male-male sexual behavior in fruit flies.

A long-standing conundrum in biology is explaining why so many animal species engage in same-sex behavior. From an evolutionary perspective, it appears counterproductive, since same-sex behavior does not produce offspring.

Yet, same-sex behavior is incredibly common. So far, about 1,500 species have been reported to partake in same-sex courtship, pair bonding, and copulation. Among them are mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, insects, mollusks, and nematodes. In French-Alpine goats, for example, one study found that female-female sexual behavior functions as a sexual stimulant for males. (Yes, you read that correctly: Scientists observed that female-female sexual behavior makes male goats horny.)

Another study, focused on pigeons, found that when males were removed, females paired and successfully raised chicks. The same pairing occurred with males when the females were removed, but things went less smoothly: The association was short-lived, as they couldn’t stop bickering with each other.

Genetics of same-sex behavior

Despite its widespread occurrence, the biological mechanisms driving same-sex sexual behavior have, so far, been elusive. However, a new study published earlier this year in the EMBO Journal offers an unexpected insight.

While a team of Chinese researchers was studying the role of a gene called “Myc” in the development of cancer in fruit flies, they noticed an unusually high level of male-male sexual behavior. But this only occurred among males that carried mutations in the Myc gene.

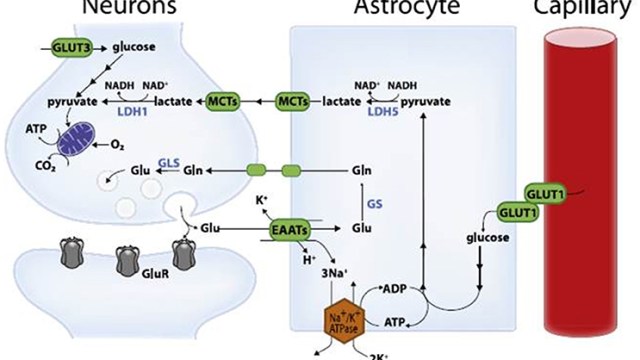

Under normal circumstances, the protein produced by the Myc gene blocks the expression of another gene called Ddc. This blocks the formation of dopamine, a neuromodulatory molecule known to facilitate courtship behavior in different species, including fruit flies and humans. Dopamine also inhibits male-male courtship in fruit flies. But when Myc is missing, dopamine is produced, and males start courting each other.

Mysteries in the genome

The authors note that the Myc gene is part of a family of genes also present in mammals, including humans, where they are called cMYC, LMYC, and NMYC. According to the authors, cMYC likely does not have the same function as Myc in fruit flies, but it is not yet known if the other two genes, LMYC and NMYC, are involved with male-male courtship. Further research is needed to fully understand the function of these genes — which may have nothing to do with sex in humans. A recent study, for example, found that Myc can increase longevity in mice by providing resistance to various age-associated pathologies, such as osteoporosis, cardiac fibrosis, and immunosenescence.

Other studies have identified potential genetic links with same-sex behavior. A 2019 study found that a mutation in a single gene led to primates losing the ability to process pheromonal signals, which might have facilitated same-sex behavior. Another recent study analyzed human genome data from 477,522 individuals from the UK and the U.S. The study found statistically significant correlations between multiple genes and different aspects of same-sex behavior, such as attraction and fantasizing.

There is a long way to go before scientists fully understand the role of genetics in sexual behavior. Unexpectedly, fruit flies are lighting the path forward.