Surprising behavior of bees during total solar eclipses discovered

- Scientists recorded the activities of bees during the 2017 total solar eclipse.

- They found that bees completely stopped flying and buzzing.

- A team of professional and citizen scientists was involved.

There is good science to be done in the unusual. Case in point – researchers just demonstrated the existence of a strange phenomenon, proving that during the solar eclipse of August 21st, 2017, bees did not buzz at all.

The research team based their hypothesis on a few previous reports which indicated that bee activity drops during eclipses. But the scientists did not expect the bees to completely stop doing everything.

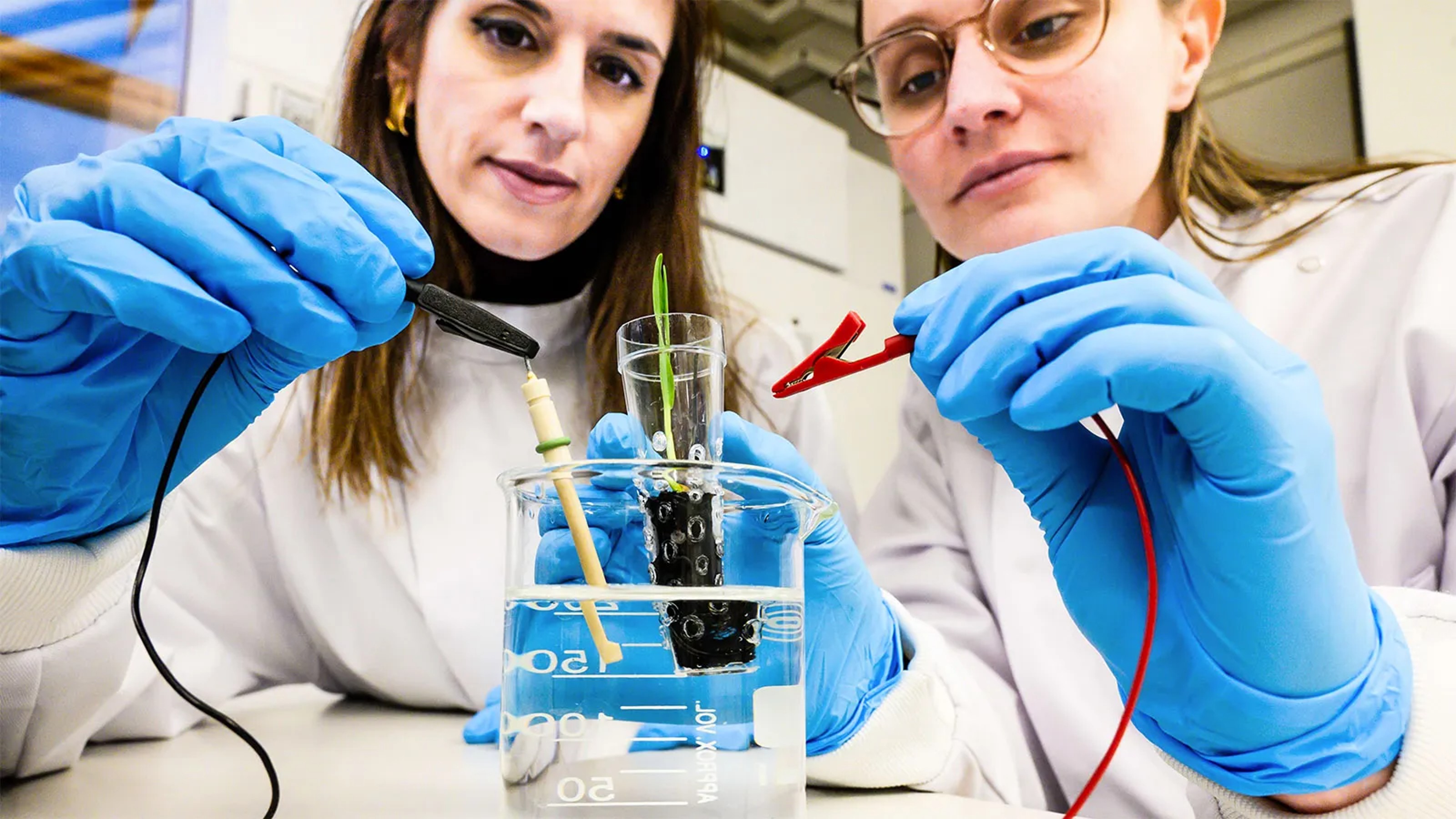

To study the question, researchers from the University of Missouri recruited a team of citizen scientists and elementary school teachers and students to set up 16 acoustic monitoring stations across Oregon, Idaho and Missouri.

Originally field-tested for remotely tracking bee pollination remotely via soundscape recordings, the stations were adapted to listen to the bees during the 2017 eclipse. They used tiny USB microphones and temperature sensors placed near flowers to record what transpired. What the devices reported is that when total darkness hit, the bees entirely ceased to buzz. As that sound is just the noise made by the bees beating their wings at 200-230Hz (cycles per second), the lack of buzzing also meant the lack of flying.

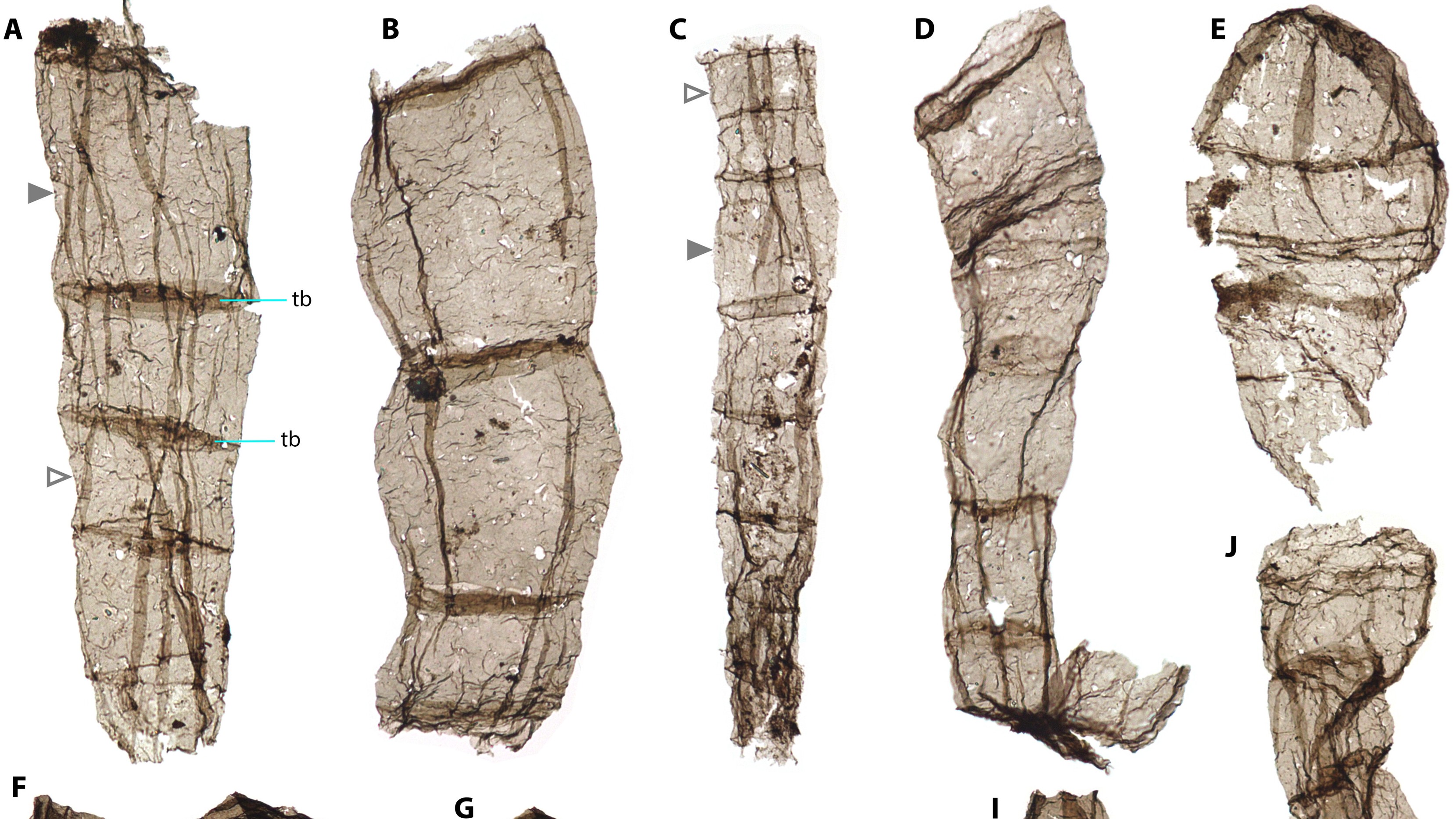

Different habitat sites of bees monitored during the total eclipse of August 21, 2017.(Candace Galen, Ph.D., University of Missouri)

Different habitat sites of bees monitored during the total eclipse of August 21, 2017.(Candace Galen, Ph.D., University of Missouri)

The study’s lead researcher, Candace Galen, professor of biological sciences at the University of Missouri, explained that the team thought there’d be differences in the bees’ behavior come the eclipse, but they had “not expected that the change would be so abrupt, that bees would continue flying up until totality and only then stop, completely.” He compared it to suddenly having ‘lights out’ at summer camp.

The research team used a grant from the the American Astronomical Society to engage more than 400 participants in the study. Members of the team hung the recording devices on lanyards next to bee-pollinated flowers, then sent the devices back to Galen’s lab for analysis.

The data showed that bees were active before and after the total eclipse but stopped all flying during the event. Of additional note is the fact that right before and after the totality, the bee flights were longer in duration. This could be due to less available light, according to the scientists. Bees tend to fly slower at dusk, returning to their colonies at night. The eclipse could have caused a similar response, suggest the researchers.

“The eclipse gave us an opportunity to ask whether the novel environmental context—mid-day, open skies—would alter the bees’ behavioral response to dim light and darkness. As we found, complete darkness elicits the same behavior in bees, regardless of timing or context. And that’s new information about bee cognition,” said Galen.

Most of the bees involved in the study were bumble bees (genus Bombus) or honey bees (Apis mellifera).

Check out the new study published in the Annals of the Entomological Society of America.