Who — or what — would survive an all-out nuclear war?

- Life will survive after a nuclear war, even though humans may not.

- A “nuclear winter” would see temperatures plummet, causing massive food shortages for humans and animals.

- Radiation would wipe out all but the hardiest of species.

Would any life remain on Earth after a total nuclear war? Yes. Life on our planet is extremely resilient. We’ve been through many mass extinctions before, some of which were probably comparable in severity to a nuclear Armageddon. In some of these events, more than 90 percent of terrestrial species died. But life always bounced back.

That doesn’t mean, however, that we Homo sapiens would necessarily survive, let alone our modern technology-dependent civilization. In fact, after a mass extinction event as severe as the one we might expect after a nuclear war, life may need millions of years to recover and regain the level of biodiversity we have today.

The realistic prospect of nuclear war

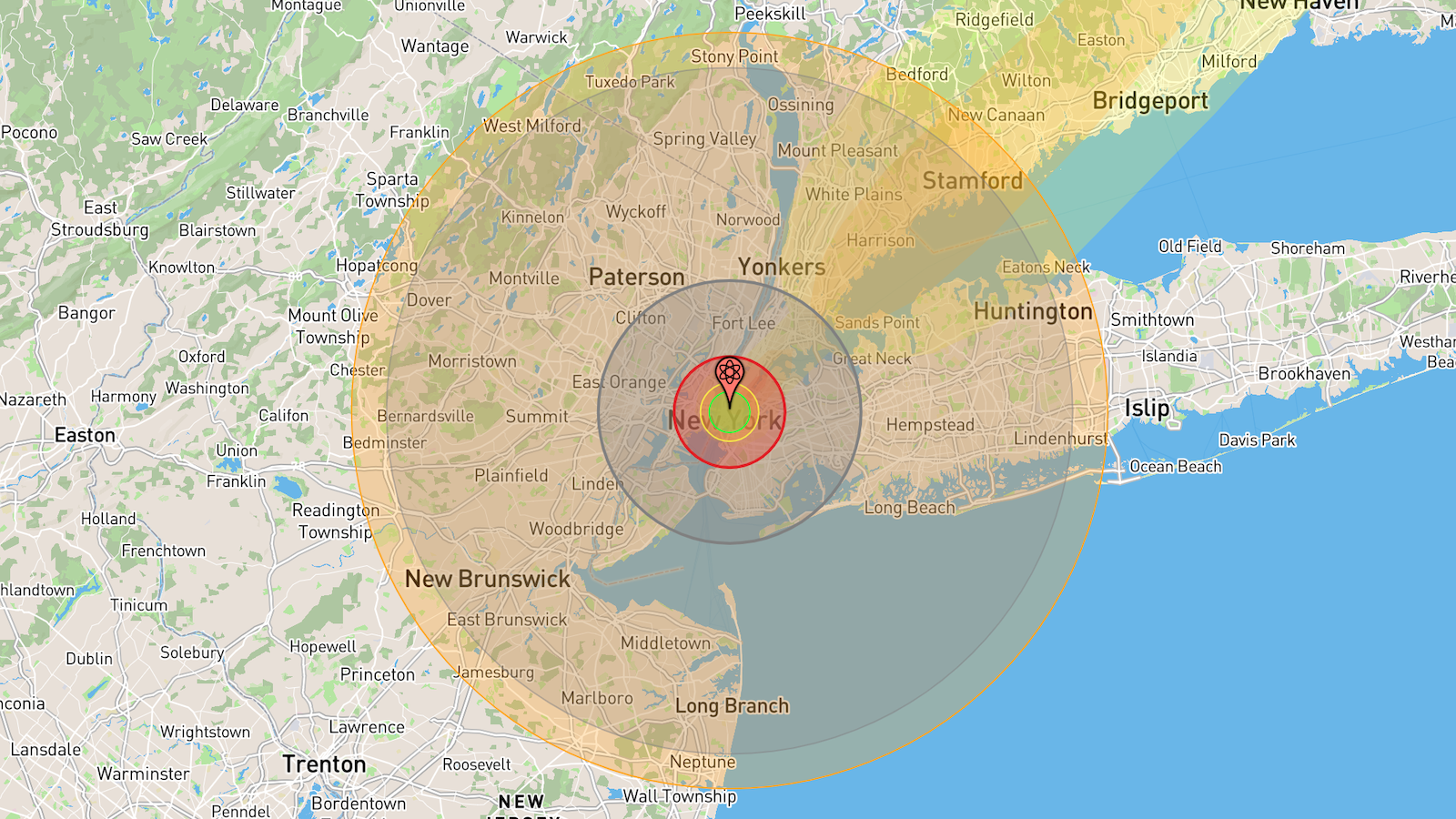

The possible effect of such a conflict has become less hypothetical recently, given the threat that Russia might escalate the war against Ukraine using tactical nukes. A large-scale nuclear war, where significant numbers of warheads are detonated (as of last count, there are more than 13,000 such weapons in the world today) would have many catastrophic consequences. The immediate effect on society was well described in a 1979 study commissioned by the U.S. Senate, which included a fictional account of the impact on one American town, Charlottesville, Virginia.

That’s only part of the picture, however. Let’s consider the long-term effects of a nuclear war on all terrestrial life forms, starting with a so-called “nuclear winter” and radiation poisoning. Recent simulations, plus data from past nuclear disasters in Chernobyl and Fukushima, give us a good idea of what the consequences would be.

Nuclear winter

A 2019 paper by Joshua Coupe of Rutgers University and colleagues, based on their simulation of a nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia, showed that about 150 million metric tons of soot (aerosols of black carbon) would be ejected into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and resulting in a drop in average global temperature of nearly 10° C for many years. Precipitation rates would decrease, and the distribution of rainfall would change drastically. The growing season in mid-latitudes would be cut by about 90 percent, and some places would get snow even in summer. The result: starvation over much of the globe, not only for humans but for many animals.

Mass starvation and worldwide fatalities also were predicted in another 2019 paper by Owen Toon and colleagues, who simulated a nuclear war between Pakistan and India in the year 2025. Even this regional conflict produced a decline of global surface temperatures of up to 5° C.

Such simulations are still very speculative, as it’s difficult to factor in all the complex environmental interactions that would follow a nuclear war. The only thing for sure is that we cannot fathom all the misery the biosphere would suffer. The effects of nuclear winter can be understood partially by comparing it to supervolcano eruptions or large asteroid impacts, although the soot from nuclear fallout would block more sunlight than an equal amount of volcanic ejecta.

Radiation

We can get a glimpse of the likely radiation effects of a nuclear war from data gathered after the Chernobyl accident of 1986 and the Fukushima accident in 2011, plus our knowledge about certain radiation-tolerant species on Earth (which, sorry to say, don’t include humans).

Radiation exposure caused considerable genetic damage and increased mutation rates in many species around Chernobyl. Mammals and birds experienced cataracts and smaller brains. But much of the original wildlife around Chernobyl has returned, and faster than expected. Plants have been shown to be more resilient than animals to radiation because they can more easily replace dead cells or tissue. Over the long term, radiation produces tumors in animals, but in plants, cancer cells typically cannot spread from one part of the plant to another, so tumors are rarely fatal.

Notably, due to the lack of human interference in the radiation-affected area of Chernobyl, the number of plant and animal species is actually greater than before the accident. Some birds have even adapted to the higher radiation levels. Several species have shown higher levels of antioxidants in their blood, which they use to mop up detrimental free radicals produced by radiation exposure.

A wasteland of microbes and scorpions

But let’s not kid ourselves. An accidental meltdown in a single nuclear power station hardly compares to a full nuclear war. Should such a catastrophe occur, people, animals, and even plants would die by the millions. What kinds of life would survive that disaster?

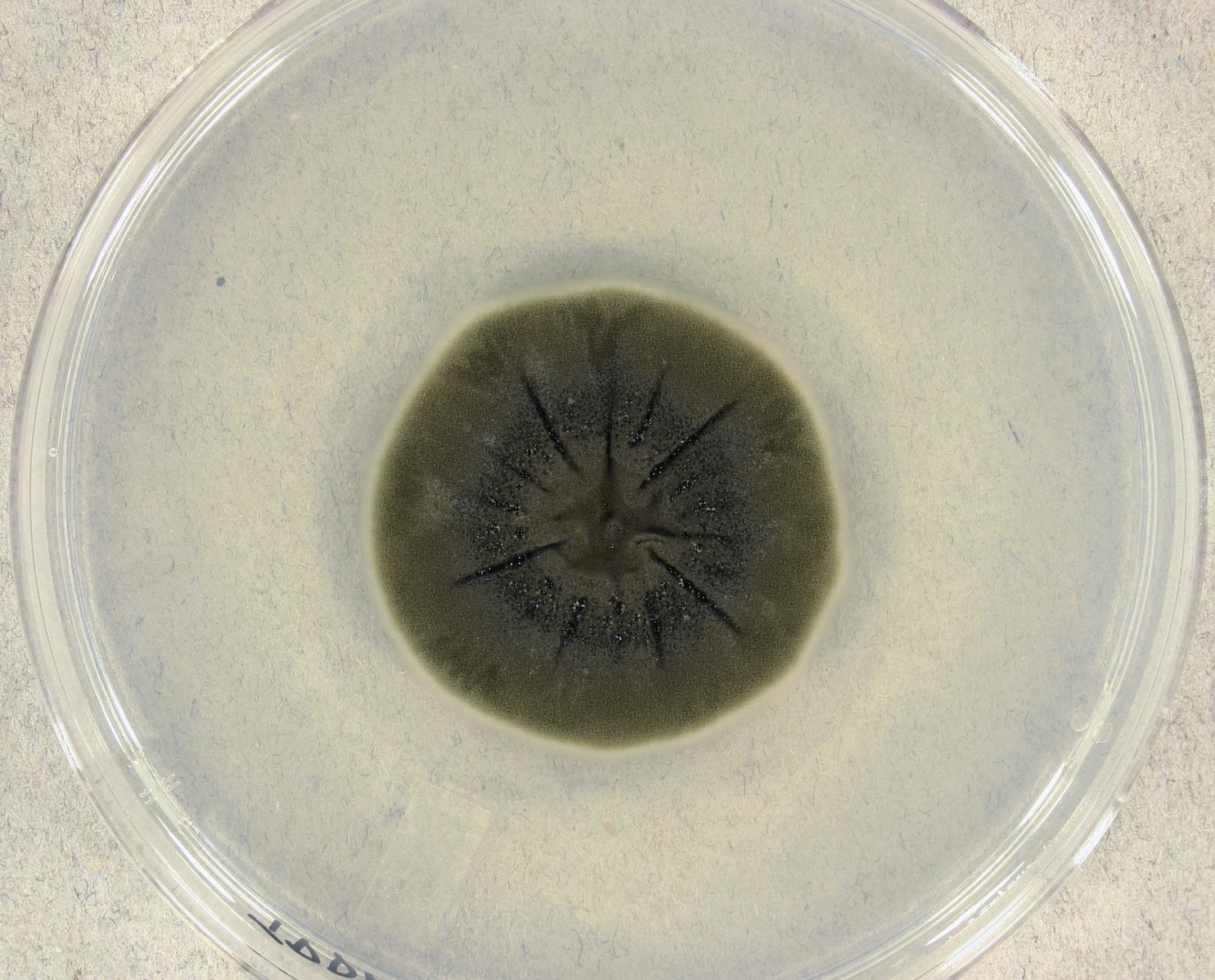

Many microbes can handle amazingly high amounts of radiation, particularly those that live in deserts. The extreme stress of living in such a harsh environment, where desiccation and higher levels of ultraviolet radiation are a constant threat, would seem to give these microbes an advantage in surviving a nuclear war. The same goes for certain large desert animals, such as scorpions.

In general, the smaller you are, the better. Possibly the most radiation-resistant organism yet discovered is Deinococcus radiodurans, which is famous for its ability to quickly repair damage due to radiation. These hardy microbes can easily take 1,000 times the radiation dose that would kill a human. As far back as 1956, it was shown that when ionic radiation was used to sterilize canned food, Deinococcus radiodurans, astonishingly, still lived on.

A type of wheel-shaped microscopic animal called bdelloid rotifers also have been found to be extremely resistant to radiation. So have tardigrades, also known as water bears or moss piglets. Some fish, like goldfish or the mummichog, are quite hardy when it comes to withstanding radiation. And the discovery of cockroaches crawling in rubble following the Hiroshima atom bomb led to the common saying that cockroaches will inherit the Earth.

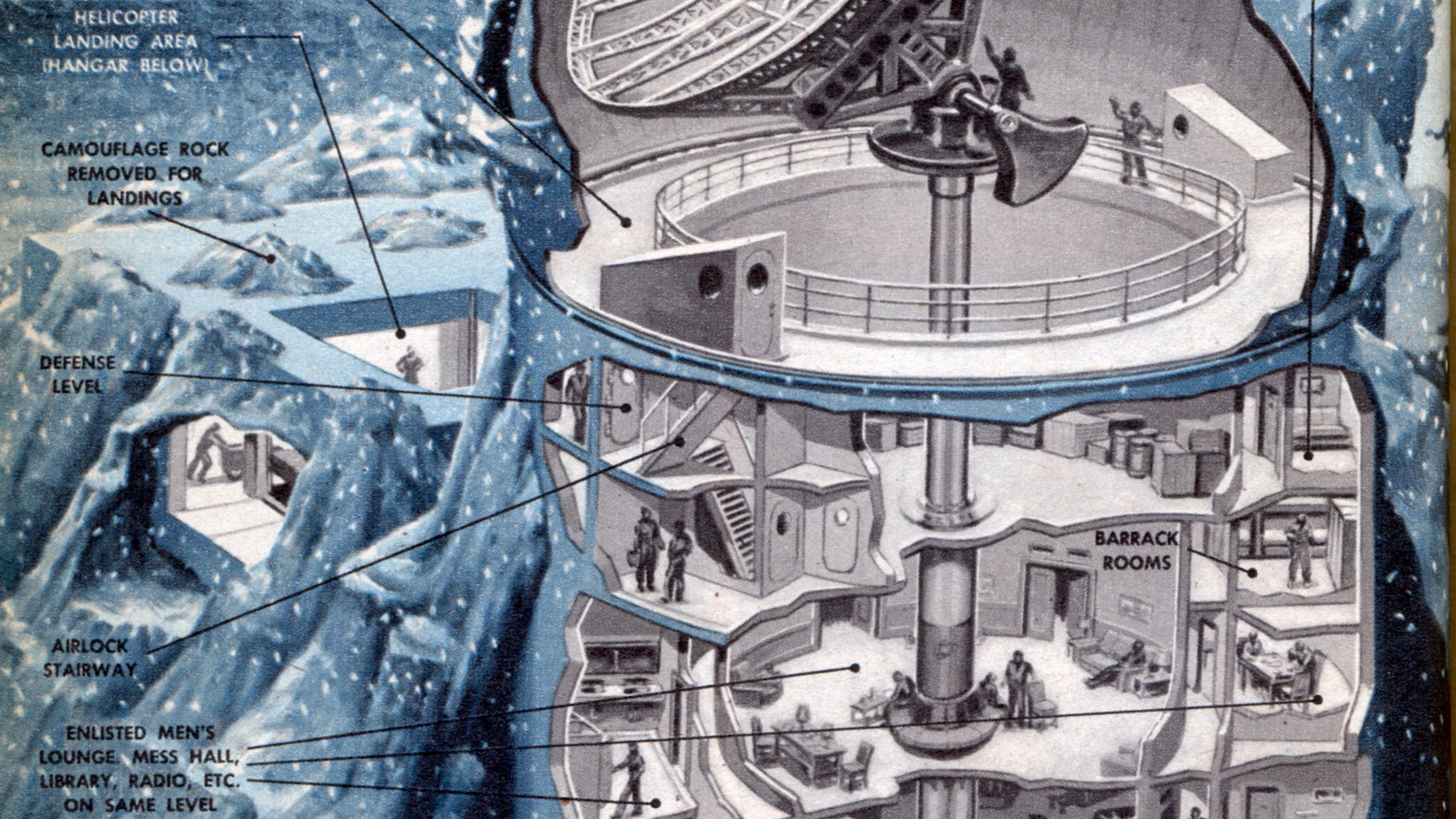

When trying to predict what types of species would survive a nuclear war, we need to consider not only radiation resistance but lifestyle. Tardigrades, for example, could survive nearly any type of radiation fallout in their dormant stage. But that wouldn’t help them much if all their food was gone when they woke up. Survival also will depend on where you live. Birds would be particularly vulnerable, as would any surface dwellers. But animals that live below ground, including one of my favorites, the naked mole rat (it may not be beautiful, but hey, beauty is in the eye of the beholder), would have a better chance of pulling through.

Rats, in general, are quite a bit more resistant to radiation than humans. Our rat-like ancestors, in fact, survived a previous extinction event — the asteroid impact that did in the (non-feathered) dinosaurs, along with many other species. These creatures lived underground, fed off of carcasses, and ushered in the age of the mammals. Is that our future? Let’s hope we have the sense to avoid nuclear war, and that we don’t end up ceding Earth to the cockroaches and scorpions.