Depression linked to disrupted circadian rhythms, UK scientists find

What causes a mood disorder like major depression or bipolar disorder? Psychiatrists say a combination of genetics, trauma, and a neurochemical imbalance. Now we find another aspect, which carries significant weight. A new study finds that disrupted circadian rhythms—our natural internal body clock, can contribute to these conditions. Researchers at the Institute of Health and Wellbeing at the University of Glasgow, in the UK, conducted the study. Their results were published in the journal The Lancet Psychiatry.

Sleep disruption is a common symptom among those with a mood disorder. There’s a chicken and egg thing going on here. Does a mood disorder disrupt sleep or does disrupted sleep cause (or worsen) a mood disorder? Most previous studies have looked at the connection subjectively.

Researchers in this study climbed through the data of 91,100 participants’ from the UK, each ages 37-73. The volunteers were part of the UK Biobank and took part between 2006 and 2010. This is a long-term research project in the UK, which according to their website investigates the “…contributions of genetic predisposition and environmental exposure to the development of disease.”

Each person involved in the study wore an AX3 triaxial accelerometer. An accelerometer tracks a person’s movement and activity. Participants wore one on their wrist 24-hours a day for one week. Later on, researchers looked at how active, intensely active, or passive each participant was during the day, at night, or at both times. Note that those who reported sleep apnea or a sleep disorder were filtered out. Each participant was also given a mental health questionnaire. The accelerometer data was cross-referenced with that from the questionnaire, to give researchers their results.

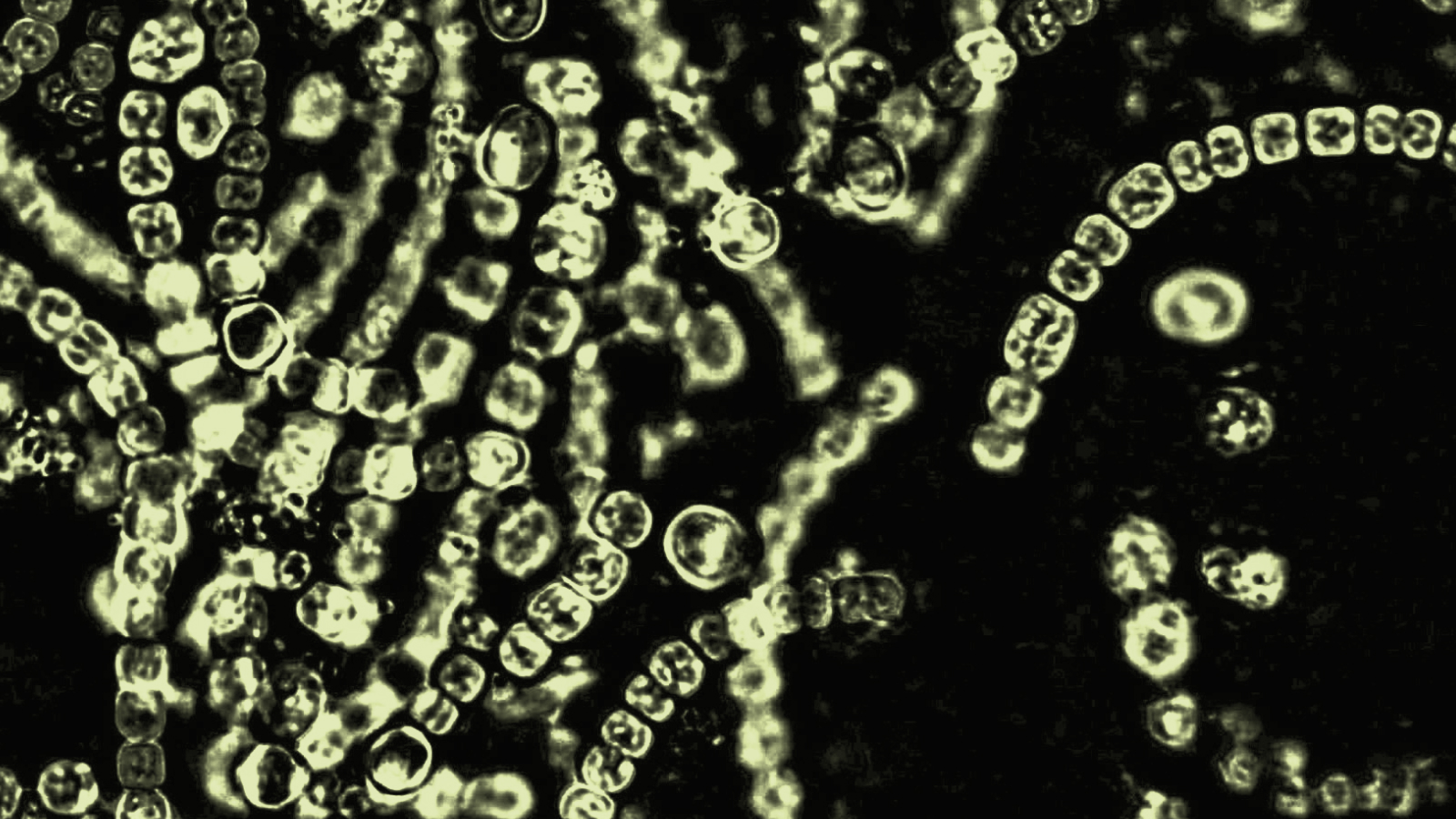

Those with a mood disorder were more likely to be active at night. Image credit: Japanexperterna.se, Wikipedia Commons.

What they found was those participants who were more active at night and less so during the day, tended to have a higher risk for lifetime bipolar or major depressive disorder. They were also lonelier, less happy, more neurotic, and had greater mood instability. Those with mood disorders and up at night tended to be men, have a higher BMI, a lower education level, and were likely to have experienced childhood trauma. There has been strong indications for some time of an association between depression and circadian rhythm disruption, so much so that some experts suggest replacing the term depression with depression-insomnia complex.

A 2010 study for instance, found that children with bipolar had a mutated RORB gene—which is responsible for one’s circadian rhythms, while a 2013 study showed depression disrupted the part of the brain that controls such rhythms. Even so, this latest study is the first to prove a direct link through actual behavioral data. Although that’s quite a step forward, causality has still not been proven.

The UK study had a pretty big limitation as well, it only monitored participants for one week. Do these same people display similar circadian patterns throughout the month, or over the course of a year? Further research will likely find out. In the future, recalibrating one’s circadian rhythms or finding proper ways to help mood disorder patients sleep, may be included in their therapy and could reap significant benefits.

To learn more about circadian rhythms and their impact on health, click here: