A Simple Principle of Educational Psychology Has Been Massively Misunderstood

A couple of years ago on this blog, we discussed at length the importance of a “growth mindset” for education, in a piece (wryly) titled: “How being called smart can actually make you stupid.” This refers to Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck’s guidance to teachers and parents to praise effort rather than talent, advice that is based on consistent evidence that doing the latter leads to drastically worse performance over time.

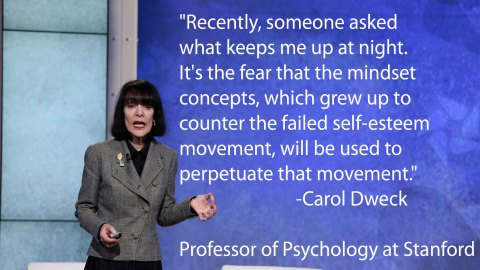

The movement, which urges teachers and parents to cultivate a “growth mindset” rather than a “fixed mindset,” has since become immensely popular with educators. Her TED talk alone has been viewed nearly 4 million times, but now Dweck believes that the message has been overcooked by some. Writing in Education Week, she explains:

“Too often nowadays, praise is given to students who are putting forth effort, but not learning, in order to make them feel good in the moment: ‘Great effort! You tried your best!’ It’s good that the students tried, but it’s not good that they’re not learning. The growth-mindset approach helps children feel good in the short and long terms, by helping them thrive on challenges and setbacks on their way to learning. When they’re stuck, teachers can appreciate their work so far, but add: ‘Let’s talk about what you’ve tried, and what you can try next.’”

Tongue firmly in cheek, Dweck writes: “If you want to make students feel good, even if they’re not learning, just praise their effort! Want to hide learning gaps from them? Just tell them, ‘Everyone is smart!’ The growth mindset was intended to help close achievement gaps, not hide them.” Dweck continues (emphasis mine): “It is about telling the truth about a student’s current achievement and then, together, doing something about it, helping him or her become smarter.”

“If you catch yourself saying ‘I’m not a math person,’ just add the word ‘yet’ to the end of the sentence.”

Dweck also raises concerns that some people now mistakenly believe that students either possess a growth mindset or a fixed mindset, resulting in a student’s mindset being blamed when in the past it would have been their environment or ability. The goal is not to just replace one prejudice with another. Instead Dweck argues that mindset itself isn’t something that is fixed, nor is it straightforward: “The path to a growth mindset is a journey, not a proclamation.”

Particularly concerning for Dweck is the idea that we could create “false growth mindsets” by trying to ban the fixed mindset outright or by trying to use mindset measures for accountability, which she warns “will create false growth mindsets on an unprecedented scale.” Dweck takes some responsibility for this risk herself, lamenting “maybe we originally put too much emphasis on sheer effort. Maybe we made the development of a growth mindset sound too easy. Maybe we talked too much about people having one mindset or the other, rather than portraying people as mixtures. We are on a growth-mindset journey, too.”

Instead, Dweck urges teachers to be careful with their use of language, which can be as simple as adding the word “yet” to a statement, for example: “If you catch yourself saying ‘I’m not a math person,’ just add the word ‘yet’ to the end of the sentence.” Ultimately, Dweck’s message is that we can’t just adopt a growth mindset and forget about it, and simply praising effort regardless of actual progress is completely counterproductive. Successfully cultivating a growth mindset is an ongoing process that consists of teaching strategies for growth and praising effort thoughtfully, rather than regardlessly.

Follow Simon Oxenham @Neurobonkers on Twitter, Facebook, RSS or join the mailing list, for weekly analysis of science and psychology news.

Hat tip: Quartz. Image Credit: NBC/Getty