It’s hard to scare people without a visual imagination

Credit: mimadeo/Adobe Stock

A strong imagination is generally viewed as being a good thing, even if at times an over-active one can result in self-induced terror as you repeat to yourself, “Just because I can vividly picture something terrible happening doesn’t mean it will.”

A study from researchers at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, Australia suggests that a visual imagination may actually be a requirement for experiencing fear. It suggests some people are less likely to be frightened simply because they lack the imagination it requires. This also means visual stimuli have a special connection to fear and perhaps other emotional experiences.

The study is published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Credit: Martin Villadsen/Adobe Stock/Big Think

It’s known that some people have trouble picturing things in their minds. This is called “mind-blindness,” or more clinically, “aphantasia.” The UNSW Sydney researchers conducted experiments to see if people with aphantasia were harder to scare.

It’s believed that aphantasia affects between two and five percent of people, and science is just beginning to understand it. Says the study’s senior author Joel Peterson of UNSW Science’s Future Minds Lab, “Aphantasia is neural diversity. It’s an amazing example of how different our brain and minds can be.”

Previous research on aphantasia at UNSW found that it’s associated with a general widespread pattern of altered cognitive process, including memory, imagination, and dreams.

Pearson says, “Aphantasia comes in different shapes and sizes. Some people have no visual imagery, while other people have no imagery in one or all of their other senses. Some people dream while others don’t.”

The new research connects aphantasia for the first time to skin conductivity, a worthy finding all by itself. “This evidence further supports aphantasia as a unique, verifiable phenomenon,” says co-author Rebecca Keogh. “This work may provide a potential new objective tool which could be used to help to confirm and diagnose aphantasia in the future.”

The current study was prompted by comments made on an aphantasia message boards expressing a disinterest in fiction for people with the condition.

Credit: pure julia/Unsplash/Big Think

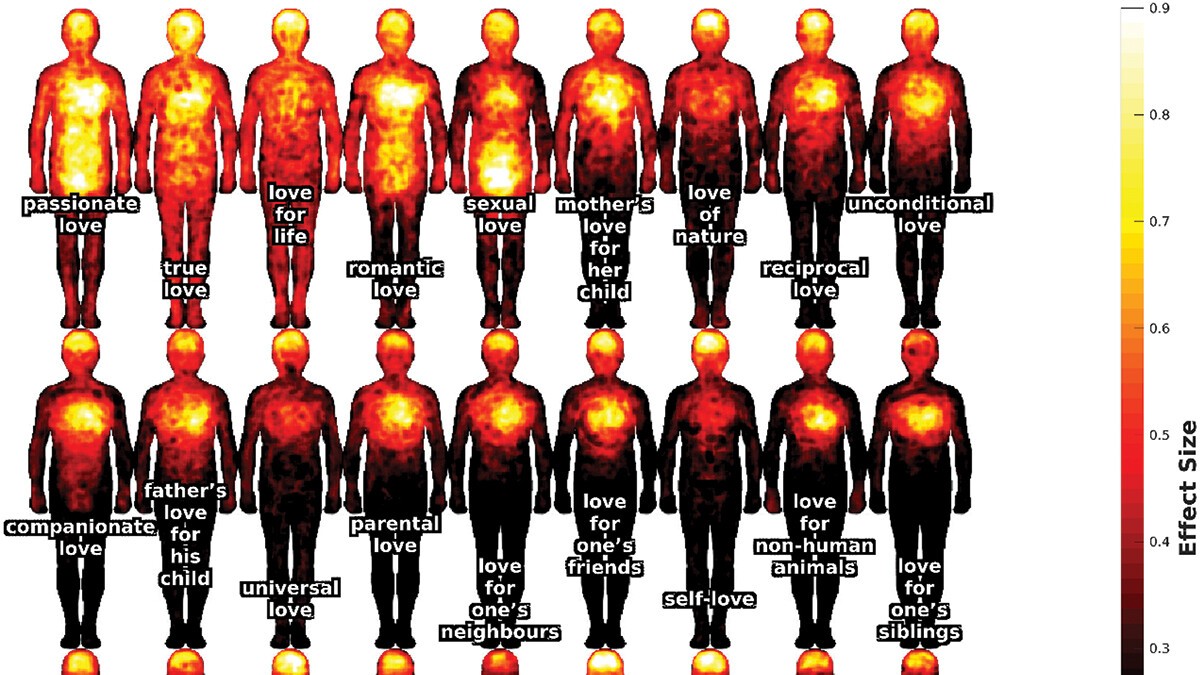

The experiments involved 22 people with aphantasia and 24 people with normal visual imaginations. Individuals were seated alone in a darkened room with electrodes attached to their skin to measure electrical conductivity. Conductivity increases when a person experiences strong emotions. Subjects were shown a succession of 3- to 7-word phrases immediately following one another, with each displayed for two seconds as they developed a frightening narrative.

The stories started innocently enough: “You are at the beach, in the water” or “You’re on a plane, by the window.” Little by little, unsettling elements were introduced — a mention of a dark flash among distant waves, or people standing on the beach pointing, or the plane shaking as the cabin lights dim.

Pearson reports, “Skin conductivity levels quickly started to grow for people who were able to visualize the stories. The more the stories went on, the more their skin reacted.”

Not so for the aphantasic participants, of whom he says: “the skin conductivity levels pretty much flatlined.”

Credit: Mark Kostich/Adobe Stock

The researchers confirmed that it was the aphantasia which accounted for the different reactions between the two groups by running the experiment again, but this time with pictures instead of words. Visual imagination wasn’t necessary — all the disturbing imagery, which included a dead human body and a snake bearing its fangs in threat, were supplied.

This time, both groups of people became similarly unnerved. “The emotional fear response was present when participants actually saw the scary material play out in front of them,” says Pearson.

“The findings suggest,” Pearson says, “that imagery is an emotional thought amplifier. We can think all kind of things, but without imagery, the thoughts aren’t going to have that emotional ‘boom.'”

It also suggests a couple of things about telling scary stories. First, the importance of visual imagination suggests that providing lots of visual details will give a scary story more oomph. Second, people with aphantasia are probably lousy campfire audiences.

Next, the researchers plan to investigate the ways in which disorders such as PTSD might be different for people with aphantasia.