A brief history of personality tests: from creepy images to probing questions

- The thematic apperception test asked people to interpret vague and sometimes disconcerting imagery.

- Though these tests fell out of favor due to their ambiguity, there seems to be some truth to them: Image interpretation might be linked to personality.

- Today, tests are administered to determine how a person scores on the “big five” core human personality traits: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

In an age before brain scanners and a variety of doodads could measure everything from eye twitches to skin conductance, the first psychologists had to be creative when it came to studying the invisible landscape of the mind.

There were two schools of thought in those early days, structuralism and functionalism. The incorporeal nature of consciousness was especially frustrating to the structuralists, who, unlike their functionalist counterparts, wanted to establish a sort of periodic table of intangible phenomena like thoughts and feelings. For example, a typical structuralist might wonder why thinking about pie was a subjectively different experience from actually eating it and whether every person’s pie thoughts were basically the same. A functionalist might wonder why people tended to eat pies on a regular basis but rarely if ever appeared in public wearing one as a hat.

Functionalists contemplated the purpose and usefulness of observable behaviors. Structuralists wanted to understand the anatomy of a person’s inner mental life, and to an outside observer, that life happened behind a bony curtain. Even if you did get a chance to peek at the goopy mess behind, that peek revealed very little.

Thematic apperception test

For many years, frustrated mind explorers in white coats devised increasingly bizarre methods to get at the invisible thoughts lurking in the black box of the skull. It was out of this frustration the projective personality test was born. You have likely heard of one of them, the Rorschach test with its butterfly-or-wolf inkblots, but there was another test invented around the same time that was just as popular, so much so that it is still used by some psychologists today.

The thematic apperception test (TAT) was invented in the 1930s by a team led by Harvard psychologist Henry H. Murray. The test went through several revisions, but the final version began printing in 1943, and in it, a psychologist would find a deck of cards with artwork attached depicting ambiguous, weird, and sometimes creepy moments.

For instance, if you were being tested with the deck, a researcher might ask you to describe what you thought was happening in a scene with four men. In the drawing, a man in the foreground seems to stare into your soul. Behind him another uses a scalpel to carve up a gentleman lying prone, and from the shadows another man watched on without explanation. Your interpretation would be recorded, and after going through a deck of these images, a psychologist would then compare and contrast your stories with those of other people who had taken that same test. The idea in the beginning was that a pattern should emerge in your answers, painting you as a certain type of person, and thus predicting your behavior in the real world.

Apperception, by the way, is different from perception. It means to make sense of novel information by putting it into a context you already understand. For example, on first viewing, you might describe Alien as “Jaws in space,” but, if you saw Alien first, you might describe Jaws as “Alien in the ocean.” In projective personality tests, psychologists were supposed to pay close attention to how you contextualized new things by comparing them to the existing material floating around in your head.

Cecilia Roberts and Christiana D. Morgan helped Murray devise the original thematic apperception test. It was based on a Carl Jung technique called active imagination. Jung encouraged studying the unconscious through something akin to meditation by prompting subjects to recall errant thoughts and visuals from dreams and then asking them to focus on the images and spin a narrative about them in a sort of trancelike, free association, vision quest. Psychologists and psychology students loved it, but getting other people to play along was usually difficult and often awkward.

Roberts, one of Murray’s students, came up with the idea of using pictures from magazines instead. She had first tried with her 4-year-old son, asking him to use his active imagination to explore his daydreams while she wrote them down. When he promptly declined, she asked him to come up with a story to describe some out-of-context photos in a book. This time he was eager to play along, and she told Murray about it who was struck with sudden inspiration for a new kind of personality test. Together, they enlisted the help of Morgan, who was a former nurse and well-known artist in certain psychology circles for providing paintings of her own active imagination adventures which Carl Jung later used in his presentations.

The operation proceeded like so: Roberts cut appropriately ambiguous images out of magazines, Morgan painted them, Murray put them into decks and began using them in the lab, and with a bit of study and analysis the TAT was born. Ambiguity was key, according to Murray, who once explained in an interview that a painting of a child huddled on the floor next to a revolver was one of his favorites, because subjects would sometimes say it was a boy and sometimes a girl, and the stories they told changed dramatically depending on that one interpretation.

Today however, although some psychologists still use them, most are wary of projective personality tests because of something that seems obvious in hindsight but somehow slipped past Murray and his team and the hundreds of people who purchased those TAT decks over the years.

As early as 1953, Murray’s peers began to notice a pernicious problem. Any one psychologist’s interpretation of any one subject’s interpretation of any one ambiguous photo was itself a kind of meta projective personality test. It became clear that in that chain of interpretations, apperception generated ambiguous personality tests all the way down — each one increasingly revealed more about the interpreter than the interpreted. Today, critics claim this trap of infinite recursion prevents psychologists from arriving at a meaningful stopping point where something useful could be derived from all that subjectivity. In fact, in 2004, a meta-analysis of this brand of meta-analyses concluded that they were largely useless when it came to predicting behavior. In time, as better methods for studying and quantifying personality traits emerged, the many forms of projective tests were relegated to the domain of Hollywood props decorating 1950s psychiatrists’ offices.

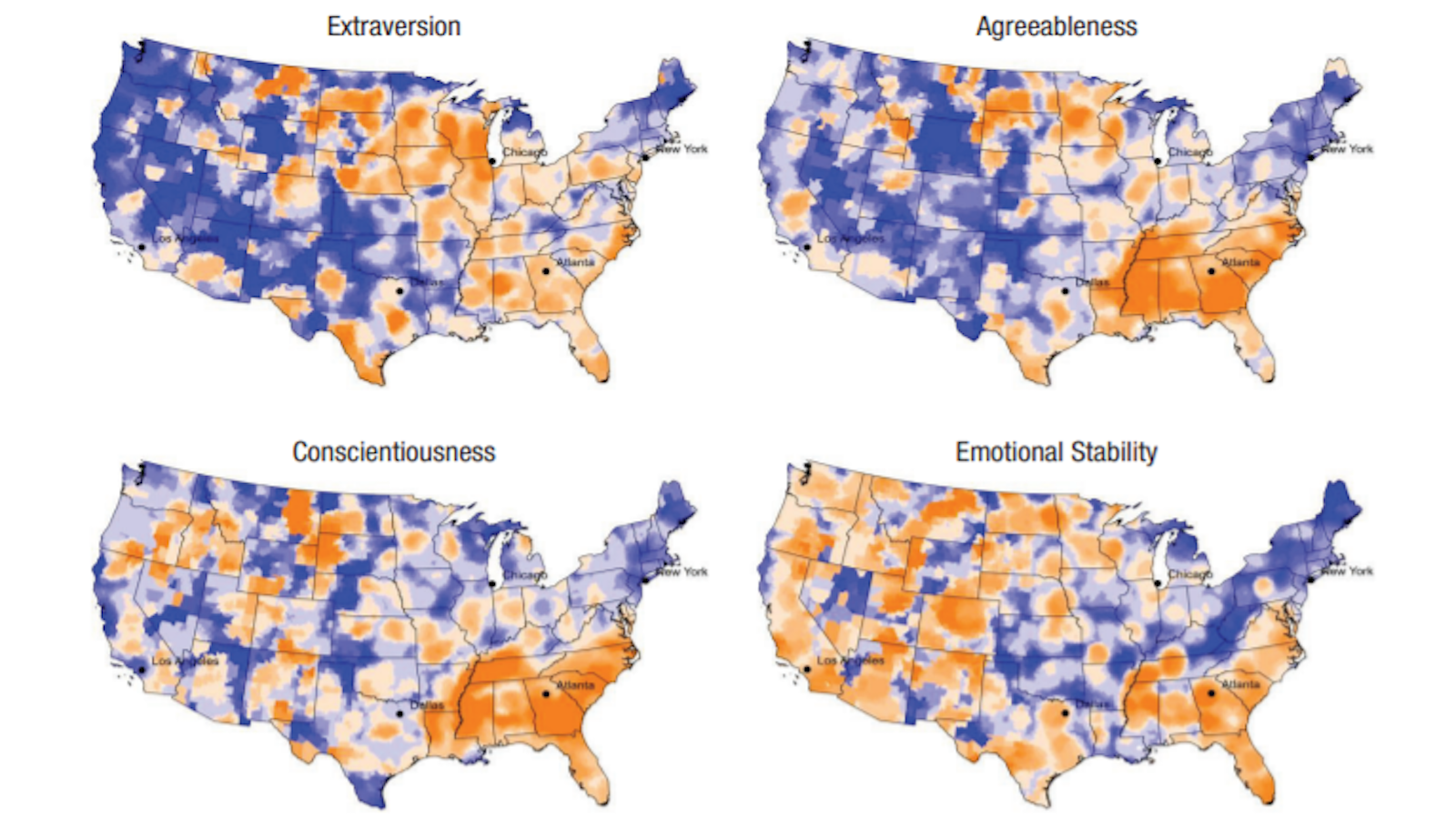

The big five personality test

Today, when it comes to understanding your personality, you are much more likely to go through a battery of questions meant to suss out where you fall on each of the traits in the five-factor model. The big five, as they call it, was developed in the 1960s and popularized in the 1980s and is now a widely adopted framework in psychology for understanding the current bestiary of agreed-upon, core human personality traits: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. The big five, unlike the TAT, has stood the test of time and replication, mostly because research using that model focused on how a person’s answers correlated with their responses in other psychological research.

For instance, recent research has shown that you can reliably determine where a person lies on the five-factor model just from the movies they consider their favorites. In a study titled, “We Are What We Watch,” researchers found that a high openness to experience correlated strongly with a preference for films like Being John Malkovich and The Darjeeling Limited, while a low openness to experience correlated with preferences for Shrek Forever After and Step Up 3D. If you love Friday Night Lights, there’s a good probability you are high in extraversion. If you’d rather watch Howl’s Moving Castle, you are likely low.

Images and personality

But there are still some echoes of Murray’s intuitions about a connection between how one reacts to images and that person’s personality. In the movie preference study, the researchers noticed some specific imagery seemed to correlate with aspects of the big five. People who gravitated toward movies with wedding scenes, for example, also scored high on openness and agreeableness. Rocket launchers: neuroticism. Hairy chests: conscientiousness.

Still, it seems the promise of peering into the mind through dream analysis, ink blot exposition, and ambiguous photograph interpretation was just a dream, for now. The academic descendants of the structuralists will need tools more powerful and more accurate than introspection alone if we can ever hope to directly observe the private subjective realities through which we make sense of the world.

But that is not to say those strange tests in the early days of psychology didn’t lead to progress. Scientists identified an important pitfall when it comes to analyzing the narrative output of brains disambiguating the ambiguous: when minds study other minds, researchers must be careful to avoid the psychological equivalent of putting a mirror in front of a mirror. (At least that’s my interpretation of their interpretation of the interpretations of interpretations.)