Neuroscientists identify a brain pathway for overcoming fear

- Mice taught to anticipate an electric shock eventually “unlearn” this fear over time.

- However, mice that lack the gene for serotonin 2C receptor forget their fear even quicker.

- The results identify a fear pathway in the brain, which might be useful for treating conditions like PTSD.

New research shows that mice lacking one subtype of serotonin receptor rapidly forget learned fear responses due to altered activity of nerve cells in the brain’s fear circuitry. The findings, published recently in the journal Translational Psychiatry, provide clues about how Prozac and related antidepressants exert their effects, and could aid the development of more effective treatments for conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Serotonin and fear

Serotonin plays a role in a wide variety of neuropsychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety. There are at least 14 different subtypes of receptor for this neurotransmitter, but the serotonin 2C receptor is known to play a crucial role in these disorders. Sandra Süß of Ruhr-University Bochum and her colleagues examined “knock-out” mice that had their serotonin 2C receptor gene deleted.

They first subjected the animals to a classical conditioning procedure. This involved administering brief, mild electric shocks to their feet, each paired with a specific sound. After repeated pairings, the animals learned to associate the two. When they heard the sound alone, they froze in place, a behavioral response indicative of fear.

In normal, “wild-type” mice, repeatedly hearing the same sound without also receiving a shock leads to “extinction” — that is, the gradual unlearning of the conditioned fear. In the knock-out mice, fear extinction occurred at a much quicker pace.

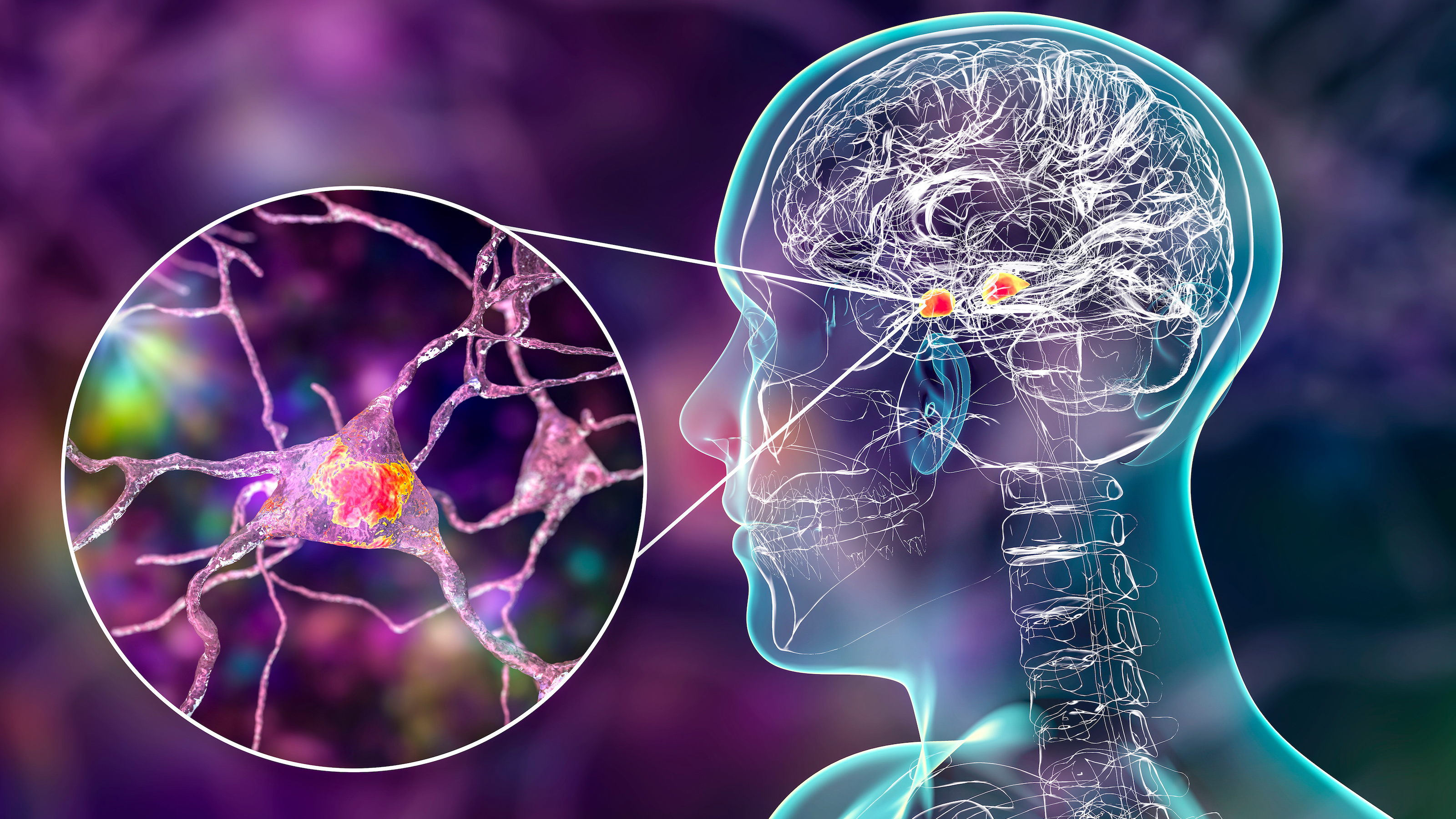

The researchers then examined neuronal activity in the animals’ fear circuitry by measuring activation of cFos, a so-called “immediate early” gene that is transiently expressed when nerve cells fire in response to a wide variety of cellular stimuli. Examination of brain tissue slices 90 minutes after extinction revealed increased activity of serotonin-producing cells in a region called the dorsal raphe nucleus, known to be involved in processing fear and anxiety, in the knock-out but not wild-type mice.

The knock-outs also exhibited altered activity in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, which mediates responses to aversive stimuli. Injection of a fluorescent tracer further showed that this is reciprocally connected to the dorsal raphe nucleus.

The fear pathway

Overall, the study showed that mice lacking the serotonin 2C receptor exhibit increased activity in a serotonin pathway connecting the dorsal raphe nucleus and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. In the dorsal raphe nucleus, serotonin 2C receptors are expressed by inhibitory neurons, which are thought to regulate stress and anxiety by a negative feedback loop. Absence of this negative feedback may be why mice lacking the serotonin 2C receptor exhibit less fear.

Long-term use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) is known to reduce anxiety, due to desensitization of serotonin 2C receptors, and the newly described mechanism may help to explain this effect.

The findings are also relevant to the treatment of PTSD. This disorder is often treated with extinction-based therapies, but the relapse rate for these techniques is high. Targeting serotonin 2C receptors with drugs could thus make the therapies more effective.