Do all humans feel music the same way?

- There’s copious scientific evidence showing that humans literally feel music, but are the sensations universal?

- Scientists recently presented nearly 2,000 participants from the United Kingdom, the United States, and China with a dozen excerpts from different songs and asked them to describe where they felt the music in their bodies.

- The researchers found that both Western and Chinese participants physically responded to the songs in nearly identical fashions.

Forty-three thousands years ago, our ancestors were making music. We know this because scientists have found unmistakable prehistoric flutes made of bone and ivory in caves nestled within a mountain range in southwest Germany. The discovery clarifies that humans evolved with rhythm and melody for at least tens of thousands of years, possibly far longer. (Alas, anthropologists will never find concrete evidence of singing; vocals don’t fossilize.)

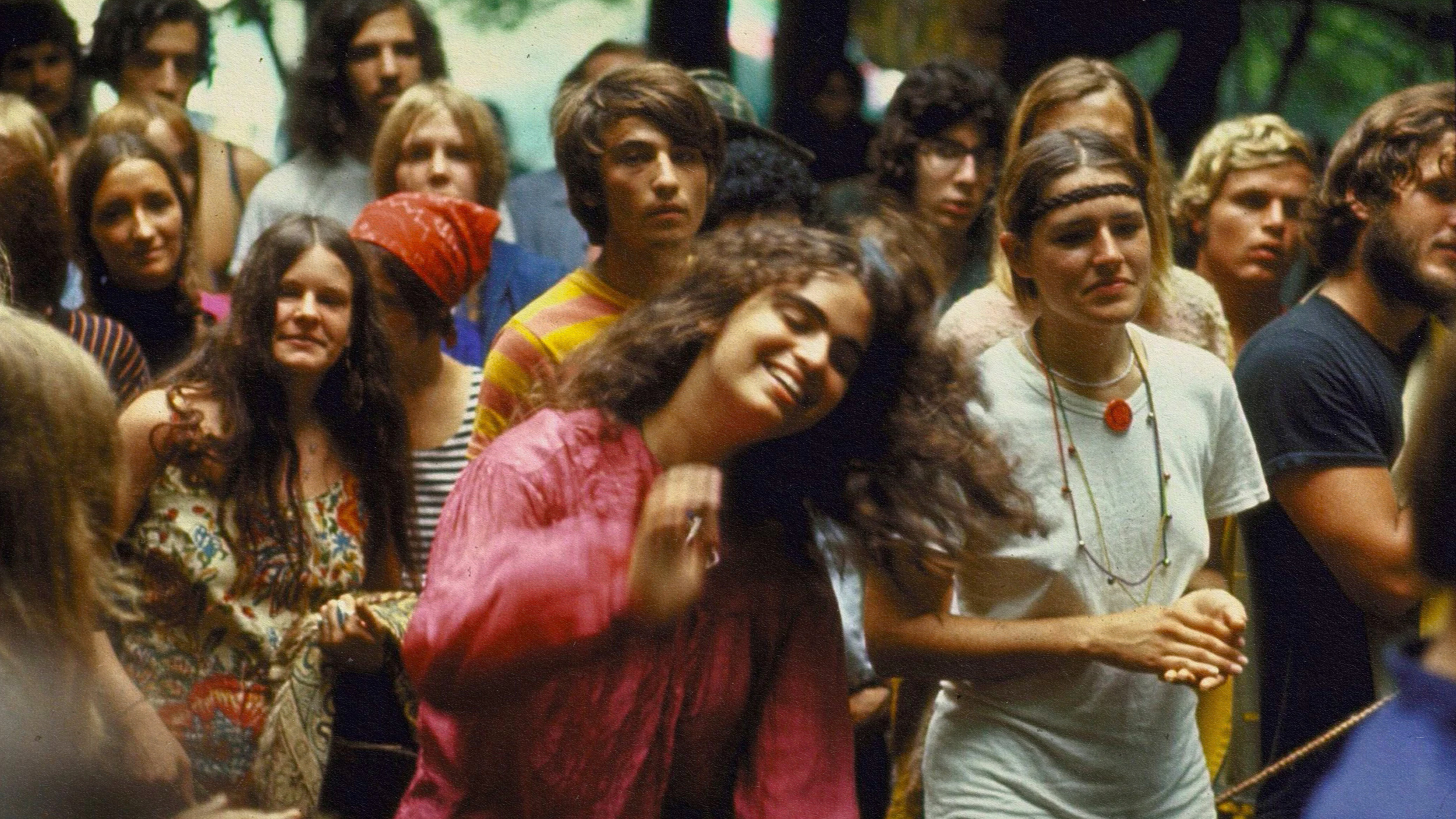

The fact that music has been with us for so long explains why it affects us so profoundly — both mentally and physically. Tears can uncontrollably seep from even the most hardened eyes when Bruce Springsteen sings “The River.” It’s hard not to nod your head with Joan Jett and the Blackhearts’ “I Love Rock ‘N Roll.” And you might not be human if you don’t at least feel an urge to groove while listening to Taylor Swift’s “Shake It Off.” We evolved to feel music.

Even infants will nod their heads and tap their feet when hearing catchy tunes. Scientists armed with fMRI scanners have found that music activates the sensory-motor regions of the brain. Furthermore, music alters heart rate, skin conductance, respiration, and body temperature. It also adjusts the levels of hormones like cortisol, oxytocin, and prolactin.

So, yes, there’s copious scientific evidence that humans literally feel music, but are the sensations universal? If humans from different cultures listen to the same songs, will they physically react in the same way?

Feeling music

That’s what a team of Chinese and Finnish researchers wanted to find out. In an experiment recently described in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they presented nearly 2,000 participants from the United Kingdom, the United States, and China with a dozen excerpts from different songs and asked them to describe where they felt the music in their bodies. For this, the researchers gave each subject blank silhouettes of a human body and asked them to color the regions where they felt changing activity.

The songs were randomly selected — one from each of six categories — from Western and Chinese cultures. The categories were aggressive, dance, happy, sad, scary, and tender. Western song selections included music from Wiz Khalifa, Rihanna, ABBA, and Slayer, among many other artists.

The researchers found that both Western and Chinese participants physically responded to the songs in nearly identical fashions.

“Across both cultures, happy and danceable songs activated the arms, legs, and the head. In contrast, sad, tender, and scary songs activated mainly the chest and head regions while for the aggressive songs, the activation was mostly focused on the head,” the researchers described. “Given the cultural consistency of these effects, the results suggest similar embodiment of musical emotions across distant cultures and point toward a biological component in music-induced bodily sensations.”

Furthermore, the results show that humans feel music in the same way regardless of language and familiarity. Participants from both Western and East Asian cultures were not very familiar with the other’s songs. Instead, their bodies were responding to specific acoustic and structural cues.

What accounts for the different ways humans feel music? Sensations in the chest could reflect changes in heart rate and respiration, the researchers say. Meanwhile, the urge to move to a steady beat could be from the brain making predictions about the musical pulse.

The authors caution that their experiment only analyzed two cultures, meaning it’s possible that a disparate group of humans living in a remote part of the world would react to music very differently.

A few years ago, scientists with the Durham University Music & Science Lab ventured to the Hindu Kush mountains of Pakistan. Their goal was simple: play various types of music for the tribal peoples there and gauge their reactions and thoughts. Lacking stable access to electricity, the tribes’ connection with the outside world was tenuous at best. So, these groups had little to no experience with other kinds of music. Would their emotional responses be drastically different from those of humans living in connected societies?

The researchers uncovered broad commonalities but also several subtle, yet intriguing differences. While music is universal, culture can — to an extent — affect our emotional responses to it.