Can AI dream? Can it love? Can it “think” in the same way we do? The short answer is: no. AI doesn’t need to bog itself down with simple human tasks like love or dreams or fear. The AI brain posits itself in a much grander scale first and then works backwards to the more human way of thinking. Joscha Bach suggests that much rather than humanoid robots, we are more likely to see AI super-brains developed by countries and larger companies. Imagine a computer brain that is designed to keep the stock market balanced, or detect earthquakes an ocean away that could sound alarms on our shores… that sort of thing.

It’s a big concept to wrap our human heads around. But as AI technology develops and grows by the day, it is important to understand where the technology is headed. Think less Rosie The Robot Maid from The Jetsons and more the computer from War Games.

Joscha Bach’s latest book is Principles of Synthetic Intelligence.

JOSCHA BACH: I think right now everybody is already perceiving that this is the decade of AI. And there is nothing like artificial intelligence that drives the digitization of the world. Historically artificial intelligence has always been the pioneer battallion of computer science.

When something was new and untested it was done in the field of AI, because it was seen as something that requires intelligence in some way, a new way of modeling things. Intelligence can be understood to a very large degree as the ability to model new systems, to model new problems.

And so it’s natural that even narrow AI is about making models of the world. For instance our current generation of deep-learning systems are already modeling things. They’re not modeling things quite in the same way with the same power as human minds can do it—They’re mostly classifiers, not simulators of complete worlds. But they’re slowly getting there, and by making these models we are, of course, digitizing things. We are making things accessible in data domains. We are making these models accessible to each other by computers and by AI systems.

And AI systems provide extensions to all our minds. Already now Google is something like my exo-cortex. It’s something that allows me to act as vast resources of information that get integrated in the way I think and extend my abilities. If I forget how to use a certain command in a programming language, it’s there at my fingertips, and I entirely rely on this like every other programmer on this planet. This is something that is incredibly powerful, and was not possible when we started out programming, when we had to store everything in our own brains.

I think consciousness is a very difficult concept to understand because we mostly know it by reference. We can point at it. But it’s very hard for us to understand what it actually is.

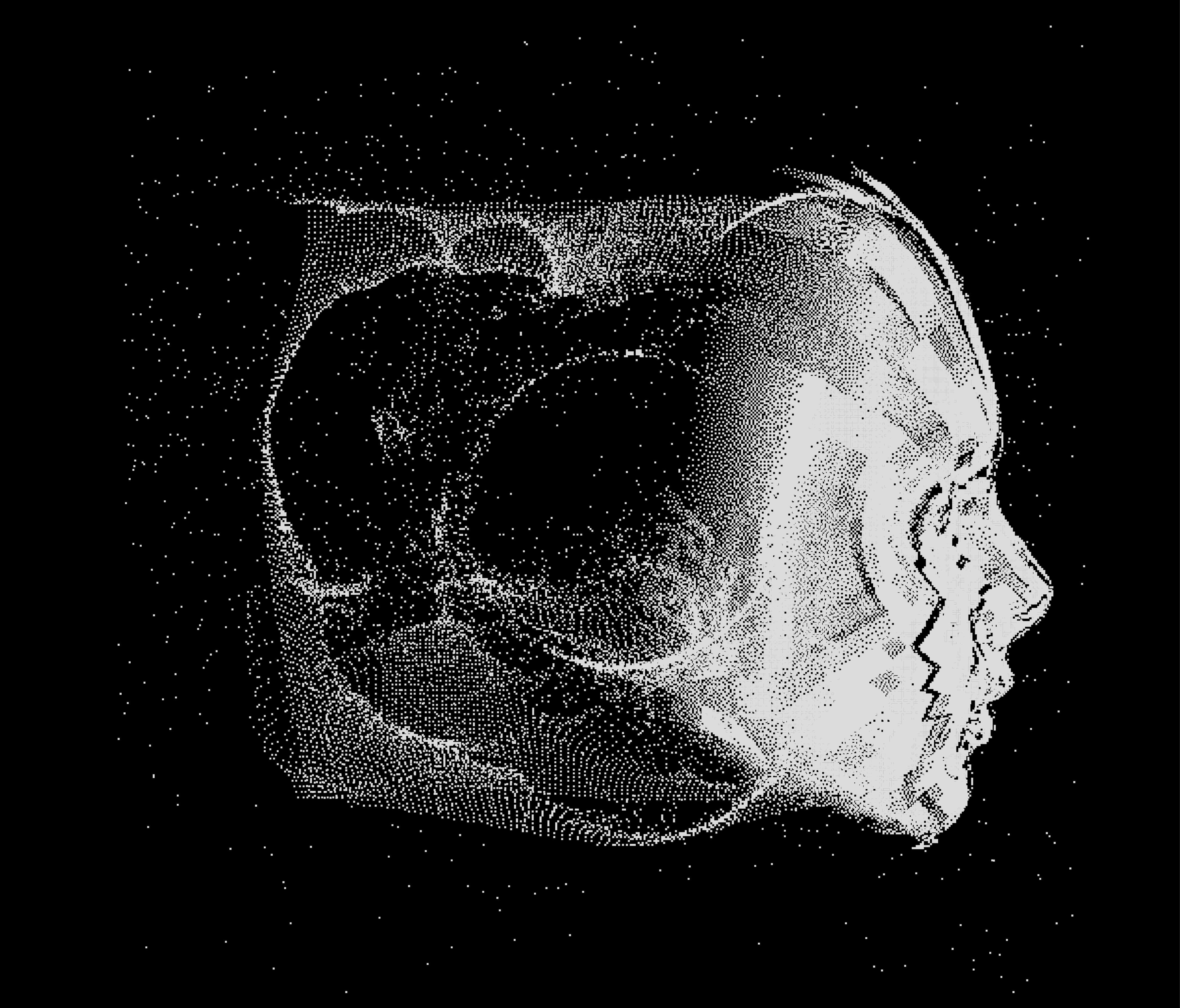

And I think at this point the best model that I’ve come up with—what we mean by consciousness—it is a model of a model of a model. That is: our new cortex makes a model of our interactions with the environment. And part of our new cortex makes a model of that model, that is, it tries to find out how we interact with the environment so we can take this into account when we interaction with the environment. And then you have a model of this model of our model which means we have something that represents the features of that model, and we call this the Self.

And the self is integrated with something like an intentional protocol. So we have a model of the things that we attended to, the things that we became aware of: why we process things and why we interact with the environment. And this protocol, this memory of what we attended to is what we typically associate with consciousness. So in some sense we are not conscious in actuality in the here and now, because that’s not really possible for a process that needs to do many things over time in order to retrieve items from memory and process them and do something with them.

Consciousness is actually a memory. It’s a construct that is reinvented in our brain several times a minute.

And when we think about being conscious of something it means that we have a model of that thing that makes it operable, that we can use.

You are not really aware of what the world is like. The world out there is some weird quantum graph. It’s something that we cannot possibly really understand —first of all because we as observers cannot really measure it. We don’t have access to the full bit-vector of the universe.

What we get access to is a few bits that our senses can measure in the environment. And from these bits our brain tries to derive a function that allows us to predict the next observable bits.

So in some sense all these concepts that we have in our mind, all these experiences that we have—sounds, people, ideas and so on— are not features of the world out there. There are no sounds in the world out there, no colors and so on. These are all features of our mental representations. They’re used to predict the next set of bits that are going to hit our retina or our eardrums.

I think the main reason why AI was started was that it was a science to understand the mind. It was meant to take over where psychology stopped making progress. Sometime after Piaget, at this point in the 1950s psychology was in this thrall of behaviorism. That means that it only focused on observable behavior. And in some sense psychology has not fully recovered from this. Even now “thinking” is not really a term in psychology, and we don’t have good ways to study thoughts and mental processes. What we study is human behavior in psychology. And in neuroscience we mostly study brains, nervous systems.

My answer is something different, in between. There are what brains do and there are the reason for our behavior. And this means there is some information processing that is facilitated by brains and that serves to produce particular kinds of behavior. And this information process then can be studied with the science of information processing, which happens to be computer science. So AI was by no accident started as a subfield of computer science.

But one of its major interests was always the understanding of what minds are, what we are, what’s our relationship to the universe.

And I think you can argue that along the way AI has lost its focus because there were more obvious benefits with automation, it was much easier to make progress. And many of the paradigms that needed to be understood and invented were not available in the first decades of the field.

Right at the beginning of the field of artificial intelligence people asked themselves, “How do we recognize that a system is intelligent?”

And often in this context we think about the Turing test. The idea of the Turing test is that you build a computer that can convince its audience that it is intelligent. But when we look for intelligence we actually look for something else. We are looking for systems that are performing a Turing test on us.

What that means is that the system checks what we are conscious of. It’s what we do with each other all the time. We try to find out, “What does the other person think? What did the other person understand? Which parts of the world does this person have consciousness of? What parts of the world is this person able to model?”

And when we will have built an AI that is truly intelligent we’ll probably recognize its intelligence, in a way, by the thing asking us and checking whether we are intelligent and conscious of the same things that it understands by itself.

It’s because the system is able to understand that itself is a mind, that it’s conscious of certain things and not of others, and the same must be true for its interlocutors.

I do think that when we build a system that is able to implement the same functionality as our brain and has to perform similar tasks that it would have similar consciousness to ours.

In practice that’s rarely going to be the case. The AIs that we are going to build in the future are probably not going to be humanoid robots for the most part. It’s going to be intelligent systems. So AIs are not going to be something that lives next to us like a household robot or something that then tries to get human rights and throw off the yoke of its oppression, like it’s a household slave or something.

Instead it’s going to be, for instance, corporations, nation states and so on that are going to use for their intelligent tasks machine learning and computer models that are more and more intricate and self-modeling and become aware of what they are doing.

So we are going to live inside of these intelligent systems, not next to them. We’re going to have a relationship to them that’s similar to the gut flora has to our organism and to our mind. We are going to be a small part of it in some sense.

So it’s very hard to map this to a human experience because the environment that these AIs are going to interact with is going to be very different from ours.

Also I don’t think that these AIs will be conscious of things in the same sense as we are, because we are only conscious of things that require our attention and we are only aware of the things that we cannot do automatically.

Most of the things that we do don’t require our attention. Most of the simple stuff in our body is regulated as feedback loops. And most of the other stuff is just going on by itself because we have entrained our brain with useful routines to deal with them. And only when there is a conflict between these routines, then we become aware and something gets our attention and we start experiencing it and integrating into our protocol.

And I think there is an argument to be made that even if we build human-like intelligence that is self-perfecting it might become so good at its tasks that it’s rarely going to be conscious of what it’s doing because it can do all automatically.