Study: Brains replay activities during sleep

Image source: Kinga Cichewicz/Unsplash/Hasbro/Big Think

- Most research in this area is done with non-human subjects, and this study validates earlier findings.

- The brain replays activities that occurred during wakefulness as you doze, or while it’s “offline.”

- Micro electrodes used in BCIs provide unprecedented access to brain functions.

People have probably always wondered what, exactly, is going on in our heads that produces our crazy-quilt dreams. Recent research suggests that it all has to do with memory consolidation as our brains weed through the prior day’s experiences to identify the stuff that merits long-term storage.

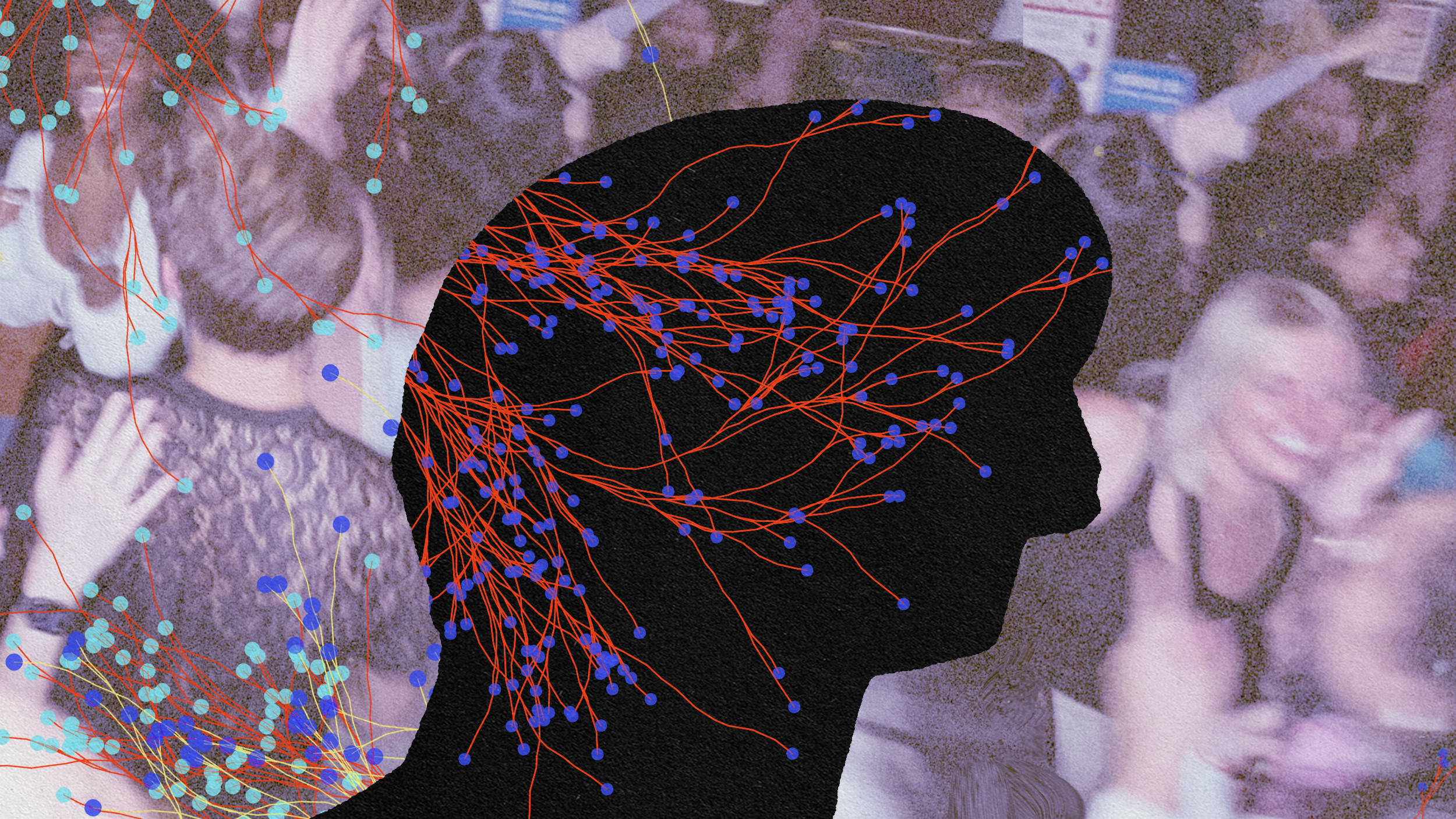

There has been indirect evidence that part of the process involves mentally replaying the day’s activities. A new study involving two subjects with implanted brain-computer interfaces (BCI) provides the most direct proof yet that this is indeed part of what’s going on. “This is the first piece of direct evidence that in humans, we also see replay during rest following learning that might help to consolidate those memories,” says first author of the study Beata Jarosiewicz

The study is the work of researchers from BrainGate, an academic research consortium involving scientists from Brown University, the Providence VA Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Case Western Reserve University, and Stanford University. “Replay of Learned Neural Firing Sequences during Rest in Human Motor Cortex” is published in the May 5 issue of Cell Reports.

Image source: National Cancer Institute/Unsplash

Scientists’ suspicion

Our senses stay busy, pulling in new information all day. In addition to the events to which we pay attention, sights, sounds, smells, and so on are being received continually. From this barrage of stimuli we learn to recognize the things that require our attention, but even the things we barely notice consciously don’t escape notice by our brains.

Those of us intrigued by our dreams find that most of what appears scrambled into them has made some sort of appearance in our waking lives over the last day or two. Sometimes it’s those things directly, sometimes they’re represented by some sort of symbolic stand-in — that movie star in your dream may be playing the part of someone actually in your life, for example — but the odd little bits that pop up make it clear that even the most casual inputs throughout the day stick, at least temporarily. But which stuff deserves remembering for a long time?

According to “Memory, Sleep and Dreaming: Experiencing Consolidation“:

“There is strong evidence that at least one function of sleep is to ‘consolidate’ fragile new memory traces into more permanent forms of long-term storage, integrating key features of recent experience with existing remote and semantic memory networks.”

The same article notes, “Behavioral studies in humans have clearly demonstrated that post-learning sleep is beneficial for human memory performance in a variety of learning domains.”

Previous, non-human research

The earliest research suggesting that the brain replays recent experiences as we sleep — when our brains are “”offline,” so to speak — showed that hippocampal “place cells” of rodents re-fired in sleep in the same order as they had when the animals ran along a track just prior to sleeping. (The hippocampus is a brain region associated with memory.)

Since then, activity replays while offline have been observed in various cortical and subcortical areas in non-humans. Non-invasive evidence from humans has also provided further, albeit indirect, evidence, suggesting replays of cerebral activity during sleep for:

- odors to which the subjects had been previously exposed

- leaning-related brain activity

- motor areas following movement learning.

Image source: Cash, et al

The new study

Lacking has been direct evidence of such replays in humans. Jarosiewicz points out, “There aren’t a lot of scenarios in which a person would have a multi-electrode array placed in their brain, where the electrodes are tiny enough to be able to detect the firing activity of individual neurons.” Electrodes approved for human implantation, such as those used in treating Parkinson’s or epilepsy, aren’t sensitive enough.

The solution was the brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) developed by BrainGate. These are intracortical micro electrode arrays that allow patients with severe motor disabilities to regain a measure of control by moving mouse cursors and operate robotic arms and assistive devices with their mind, or more specifically, brain waves. (We’ve written before about the powerful potential of BCIs before at Big Think.) BCIs had already been implanted in the study’s two participants as part of clinical trials for the device.

For the study, they took naps both before and after playing a version of the popular game Simon as brain activity was monitored through their BCIs. The researchers observed the same neuronal patterns firing off as the game was played and then again during the post-play nap.

The authors report, “We compare the firing rate patterns that caused the cursor movements when performing each sequence to firing rate patterns throughout both rest periods. Correlations with repeated sequences increase more from pre- to post- task rest than do correlations with control sequences, providing direct evidence of learning-related replay in the human brain.”

Jarosiewicz enthuses, “All the replay-related memory consolidation mechanisms that we’ve studied in animals for all these decades might actually generalize to humans as well.”

While the exact mechanisms the brain uses to sort and consolidate memories during sleep remain unknown, this study nonetheless supports the notion that answers derived from animal studies may turn out to be applicable to human beings as well, something that can’t be assumed. It’s an impressive testament to the use of human microscale neural recording systems in research.

For now, Jarosiewicz says we can probably take for granted conventional wisdom that getting a good night’s sleep “before a test and before important interviews” can genuinely help. At the very least, now “we have good scientific evidence that sleep is very important in these processes.”