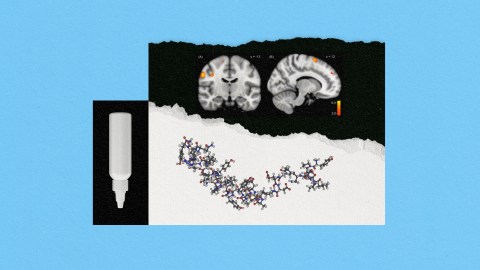

Nasal drops might prevent PTSD

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized by intrusive fear memories that do not diminish, or “extinguish,” over time.

- A small protein called neuropeptide Y is known to play a role in PTSD.

- New research shows that nasal drops of neuropeptide Y triggers extinction of fear memories in an animal model of PTSD. Combined with pre-existing data from a clinical trial in humans, this suggests that these nasal drops could prevent the development of PTSD.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized by an exaggerated fear response to stimuli related to a traumatic event, which persists long after the event has taken place. Normally, learned fear responses gradually diminish over time, but research suggests that this process, called extinction, is impaired in PTSD.

Neuropeptide Y

Research also shows that neuropeptide Y (NPY) plays a role in PTSD. This small protein has anti-anxiety and neuroprotective properties, and various studies show that PTSD is associated with reduced concentrations of NPY in the brain. Research just published in the Journal of Neuroendocrinology now shows that an NPY nasal spray prevents PTSD-like behaviors in mice by triggering extinction of fear memories.

NPY is a 36-amino acid protein that is usually highly concentrated throughout the brain and peripheral nervous system, where it plays a role in multiple processes, including appetite, energy homeostasis, pain processing, and stress regulation. In humans, genetic variations in NPY expression affect emotions and the stress response, and combat veterans with PTSD have significantly lower levels of the peptide in their blood and cerebrospinal fluid than those without PTSD. In animals, administration of NPY into the brain inhibits different kinds of stress-induced behaviors.

How to give a rat PTSD

Esther Sabban of New York Medical School and her colleagues investigated the effects of a nasal NPY spray on the learning, retention, and extinction of fear memories in rats after exposure to a traumatic event. The researchers immobilized rats for two hours then forced them to swim for 20 minutes. After a brief recuperation period, they anesthetized the animals with ether vapor and put pairs into cages. This so-called “single prolonged stress” procedure has been used as an animal model of PTSD for 25 years.

While under anesthesia, some of the animals were given NPY, delivered as drops into their nostrils. One week later, all the animals were placed into a chamber, where they received mild electric shocks to their feet, paired with a sound, so that they learned to associate the sound with the shocks.

The next day, they were placed in another chamber, where they heard the same sound again repeatedly, without receiving electric shocks. Normally, this would cause gradual extinction of the learned fear memory, so that the initial fear response to the sound diminishes over time. In the animals subjected to prolonged stress a week earlier, this fear extinction did not occur, and they continued to exhibit fear behaviors in response to the sound. And when placed on an elevated maze, they behaved anxiously and froze instead of exploring the environment.

But the rats given nasal drops of NPY after exposure to prolonged stress behaved differently. Their fear responses did extinguish with repeated exposure to the sound in the absence of electric shocks, and they also explored the elevated maze without displaying anxiety-like behavior. Their behavior resembled that of control animals that were handled gently for several minutes instead of being subjected to the stressful procedure.

Clinical trials in humans

A small trial published in 2018 showed that intranasal NPY is well tolerated by PTSD patients, and may have anti-anxiety effects. These latest results suggest that intranasal NPY has potential as an early, non-invasive intervention that could prevent development of the condition in the first place.