Rats ‘feel the distress’ of other rats, Dutch neuroscientists say

Image source: Ukki Studio/Shutterstock

- A new study demonstrates that a rat will respond to another’s pain.

- Freezing in place as another rat is shocked is one of empathy’s visible indicators.

- The rats’ mechanism for feeling the distress of others seems to be similar to our own.

When we feel pain, an area of our brain, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), becomes active. And interestingly, it also activates when we observe someone else’s pain. While we don’t literally feel their pain physically, we do feel it emotionally. It’s believed that this is due to “mirror neurons” in our cingulate cortex.

A new study from Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience, published in Current Biology on April 11, has found that rats also react to others’ experiences, and that this is also due to mirror neurons in their ACC (area 24). While it’s interesting and potentially helpful for research that rats experience this via a similar mechanism to ours, the more powerful finding is that rats feel for one another, the latest sign that animals have capabilities we often neglect to give them credit for.

It also calls into question the empathy of human researchers conducting experiments such as these that deliberately and repeatedly inflict pain in laboratory animals.

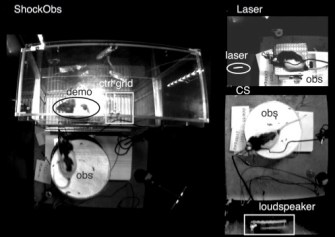

Image source: study

How scientists prepared the observer rats

In the study, the researchers utilized rats’ tendency to freeze in place when confronted with a perceived risk.

To train the “observer” rats, silicon probes for fMRI monitoring of electrical activity were surgically implanted in the rats’ heads. They were then pre-conditioned for 2–3 weeks during which electrical shocks were applied to their paws sufficient to cause them to freeze up in pain. Eventually, the scientists trained the rats to associate a particular audio tone with electroshocks as a fear-conditioned sound (CS). Finally, to establish baseline readings of mirror neurons’ response to being shocked, they applied a CO2 heat laser in place of electroshock so as not to corrupt the monitored electrical signals.

The electroshock voltages and laser heats were pretty low by human standards — 1.5mA and 0.4mA — and the lasers aa well — 7W and 5.5W — but then, we’re much bigger than rats.

Image source: study

Watching another rat suffer

Five weeks after the start of the experiment, one observer rat watched a “demonstrator” rat being shocked. A laser was directed near, but not touching, another rat, and a third was monitored as it froze in response to the CS.

The bottom line is that when the demonstrator experienced pain, its observer reacted, even though it was not itself receiving any kind of shock, laser, or hearing the CS at the time.

The response of the area 24 mirror neurons was remarkably similar to those produced earlier when the observer rats had themselves been shocked or lasered.

Image source: study

Turning off the mirror neurons

To verify the role of the area 24 neurons, the researchers injected a pharmacological analgesia that kept the neurons from firing, and the rats’ empathetic freezing also ceased as they observed demonstrators, thus confirming that the neurons play a part in the rats being able to relate to one another’s suffering.

Given the technical difficulties of testing our own mirror-neuron circuitry, this study’s result is a close as we can get for now to confirmation of our own empathy mechanism.

Thought subjecting research animals to similar pain and discomfort is not uncommon, it’s especially ironic here, since the same experiments that confirm rats’ ability to feel others’ pain seems to cast researchers’ own empathy in doubt.