David Ropeik

Retired Harvard Instructor, Author

David Ropeik is an award-winning broadcast journalist, a Harvard instructor, and an international consultant in risk communication and risk perception. He’s also the author of How Risky Is It, Really? Why Our Fears Don’t Always Match the Facts.

There are fair quarrels with the details of the Obama Administration plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. But beyond the details, the fact that such a major step is being taken in the first place is a hopeful sign that our leaders can lead with reason and wisdom, and not just follow public opinion and emotion, as we try to find a more sustainable path to the future.

A decision requiring cellphone retailers to warn customers of possible radiation risk typifies the emotion-based way that democracy can supersede intelligent government risk policy-making.

A terrific story about the physical threat of a major earthquake in the Pacific Northwest fails to explain why people don’t seem alarmed. That lack of alarm puts the public at risk as much as the shaking Earth itself, and should be part of the story.

Most reporting about risk hypes the danger but doesn’t provide all the information the reader needs to put the actual threat in perspective. So when balanced risk reporting shows up, it should be praised.

Public apprehension about the health effects of mercury FAR exceeds the actual danger. Why, and what are the health impacts of that fear!?

There is no clearer teaching example of the emotional nature of the way we perceive risk than the annual Summer of the Shark feeding frenzy of fear in the media when a few shark attacks grab the headlines.

With angry tribal polarizing language, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia challenges the very right of the Supreme Court to judge cases that require interpretation of Constitutional Law.

The pope laments the state of the environment, but he also decries the naive central environmentalist belief that humans are separate from nature and the villain in a simple myth of US (humans) against True Nature.

Pope Francis’ message on the environment is actually a radical call for humans to accept a more modest material lifestyle, and for a major redistribution of the world’s wealth and power. That’s great stuff for a sermon, but not so helpful as a practical guide for achievable change.

Pope Francis’s moving plea to save life on Earth from a dystopian future calls on people to sacrifice some material comfort, live more modestly, and recognize that we share a common home and have a responsibility to the future. Given the nature of the human instinct to survive and prioritize ourselves over others and the immediate over the future … good luck with that, your Holiness.

The hope that humans can use wisdom and technology to prevent a bleak future for life on Earth is overly optimistic. It falsely presumes that we can use wisdom to overcome instincts.

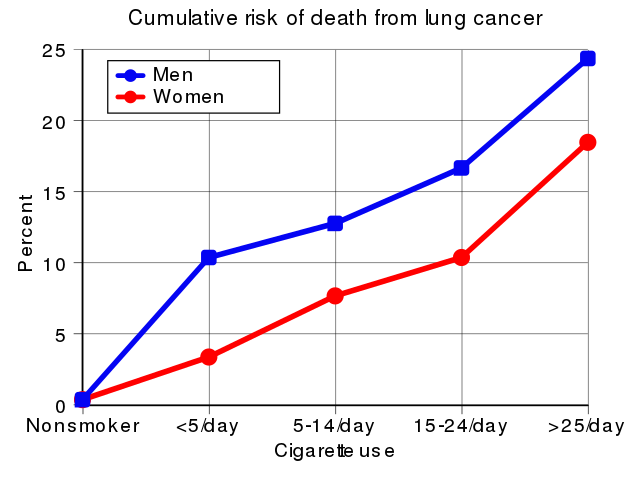

The number of new cases of cancer worldwide is rising. The death rate from cancer worldwide is dropping. What do these conflicting numbers tell us about the challenge of making sense of just how risky it is out there?

Journalists often hype the most alarming aspects of the news. In the process, they sometimes create and reinforce common fears that far exceed the actual danger.

Common assumptions about the dangers of radiation are excessive. Journalism plays a huge role in creating and feeding these fears.

GMO opponents hope labels will scare customers away and kill the technology. New evidence suggests that labels are more likely to encourage sales than reduce them.

Harsh criticism of Chipotle’s marketing ploy to eliminate some genetically modified ingredients is part of a growing movement to stand up to advocates on many issues who promote fear that flies in the face of the evidence.

News coverage of risk that plays up how scary things sound and plays down or leaves out anything that moderates the fear does real and serious harm.

How a liberal community recently voted for reason over emotion and values-based decision-making on two hot-button environmental issues.

Recent reports about radiation from the Fukushima nuclear disaster in ocean water off Canada reported the risk responsibly. At low doses, the risk is infinitesimal. More news coverage of radiation needs to say so.

We instinctively feel safer about anything natural and more worried by anything human-made, but instincts may not lead to choices that do human or environmental health the most good.

Two recent examples from The New York Times, one from a columnist and one in an editorial, illustrate the danger of news media coverage of risk that is alarmist, incomplete, and inaccurate.

Proposals to completely eliminate parental choice over whether their kids will be vaccinated can backfire and drive more parents into the anti-vaccination camp.

The massive damage humans have done to the natural world has provoked a backlash that could be just as dangerous, or more. There is a growing global rejection of technology and almost anything human-made in favor of whatever is more ‘natural’. But a simplistic rejection of modern technologies eliminates many of our best options for solving the problems we’ve created.

The massive damage humans have done to the natural world has provoked a backlash that could be just as dangerous, or more. There is a growing global rejection of technology and almost anything human-made in favor of whatever is more “natural.” But a simplistic rejection of modern technologies eliminates many of our best options for solving the problems we’ve created.

The massive damage humans have done to the natural world has provoked a backlash that could be just as dangerous, or more. There is a growing global rejection of technology and almost anything human-made in favor of whatever is more ‘natural.’ But a simplistic rejection of modern technologies eliminates many of our best options for solving the problems we’ve created.

A newly released series of anti-nuclear videos demonstrates just how blind to the evidence our underlying values can make us… and how that blindness can make it harder to solve the huge and complex problems facing modern society.

On a wide range of contentious issues, academics and researchers publish work that pretends to offer objective evidence, but which on closer inspection turns out to be advocacy masquerading behind intellectualisms, scientific methodology, footnotes and citations, and erudite language. A recent example is a paper by Nassim Nicholas Taleb and colleagues arguing that genetically modified foods pose such a risk to life on Earth that agricultural biotechnology should be banned under a strict application of the Precautionary Principle.

Designers of the new federal system for sending emergency alerts to our cellphones devoted a lot attention to setting up the technical aspects, but not enough to figuring out what the messages should say. Research suggests those messages don’t say enough to keep us safe.

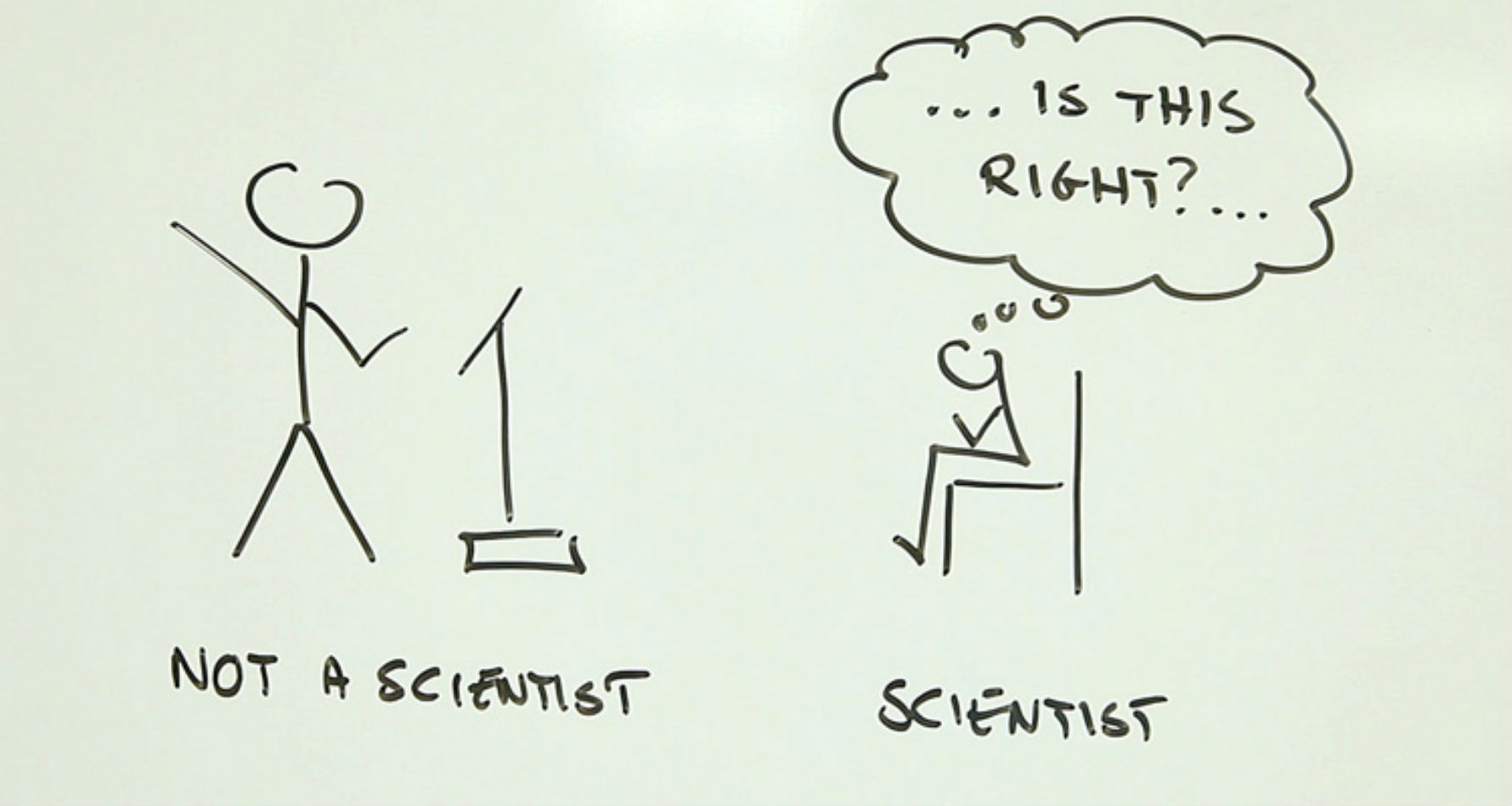

A new survey confirms that the lay public trusts science and scientists, but that scientists and the public have different views on specific issues. Unfortunately, the survey tells us how people feel, but not why, which we have to understand if we’re going to try and narrow the perception gap between what the public believes and what the bulk of the scientific evidence indicates, a gap that cause all kinds of harm.

Public opinion surveys are often cited as evidence of how people feel. What they really demonstrate is how human cognition is more a matter of emotion than reason.