Why You Shouldn’t (Always) Trust Your Gut

He hasn’t shot an episode of Let’s Make a Deal for decades, but Monty Hall’s name still graces a statistical brouhaha from the early 1990s, and the drama he cultivated on air holds enduring lessons for all of us.

You probably remember how it worked: Monty would choose a member of the audience and then offer him a choice of three doors. One door concealed a fabulous prize: a load of cash or a car. The other two doors hid dud prizes, or “zonks” — disappointments like a goat or a pair of old shoes. So the chances of winning were pretty good — 1 in 3 — and definitely better than a scratch-off lottery ticket or slot machines. But here is where the wrinkle comes in: After you chose a door, Monty would typically open one of the other two doors, revealing a zonk. He would then give you a chance to switch from your first choice to the other unopened door.

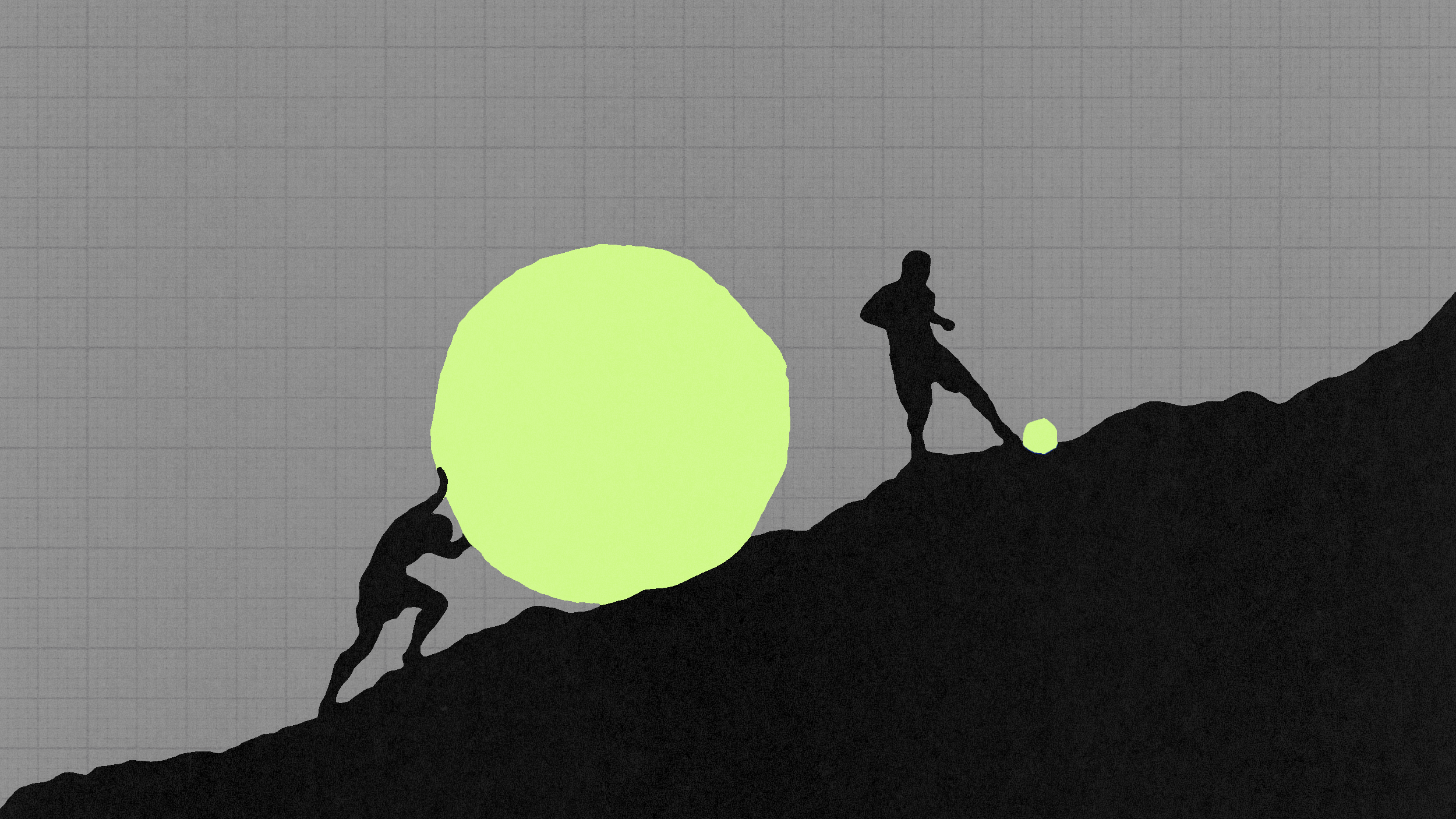

Casual statisticians — that is, normal people — assume that chances are even (1 in 2) at this stage. So it becomes a question of “sticking to your guns” or having a wandering eye and abandoning your first choice for another.

In 1990, a columnist in Parade magazine, Marilyn vos Savant, wrote an article explaining why it always makes sense to switch from your initial choice. Sticking to your guns, she tried to explain, is, statistically, a failing strategy. This position earned her a heap of vitriol. Here is John Tierney writing about the affair in The New York Times in 1991:

Since she gave her answer, Ms. vos Savant estimates she has received 10,000 letters, the great majority disagreeing with her. The most vehement criticism has come from mathematicians and scientists, who have alternated between gloating at her (“You are the goat!”) and lamenting the nation’s innumeracy.

Her answer — that the contestant should switch doors — has been debated in the halls of the Central Intelligence Agency and the barracks of fighter pilots in the Persian Gulf. It has been analyzed by mathematicians at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and computer programmers at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. It has been tested in classes from second grade to graduate level at more than 1,000 schools across the country.

There are some excellent resources for understanding why, as Mr. Tierney put it, all these Ph.D.s in math were “dead wrong.” This clear explanation from the Khan Academy will set you straight in seven minutes: