Is It Possible To Break Free From Your Political Bubble?

One of the dominant themes emerging from the last election cycle is how divided a nation we really are. Americans aren’t alone, given voter breakdown of Brexit and this weekend’s decision on choosing a new French leader—that nation’s electoral map is indicative of the American landscape as well, with liberal voters concentrated in urban centers.

What has not been clear is how to resolve this problem. Engaging with those who hold different opinions seems impossible, at least online. Add to this trolls that assume dozens of identities to blanket social media posts with incendiary rhetoric. Just last week one of my posts on Obama’s return was plastered with a slew of racist commentary and photos.

Is one “side” more open to conversation than the other? Is this even possible when many dialogues are really only heated monologues lobbed like grenades with no patience to contemplate the artillery being fired back? If helpful conversation is not possible, how much worse will it get?

Like many liberals, I recognize the bubble I exist in simply by scanning my feed and noticing the percentage of news I agree with. I log onto Breitbart regularly to sift through news in attempts of wrapping my head around what’s being presented. Yet I never engage in discussion boards, the comments completely foreign to my experiences as an American citizen.

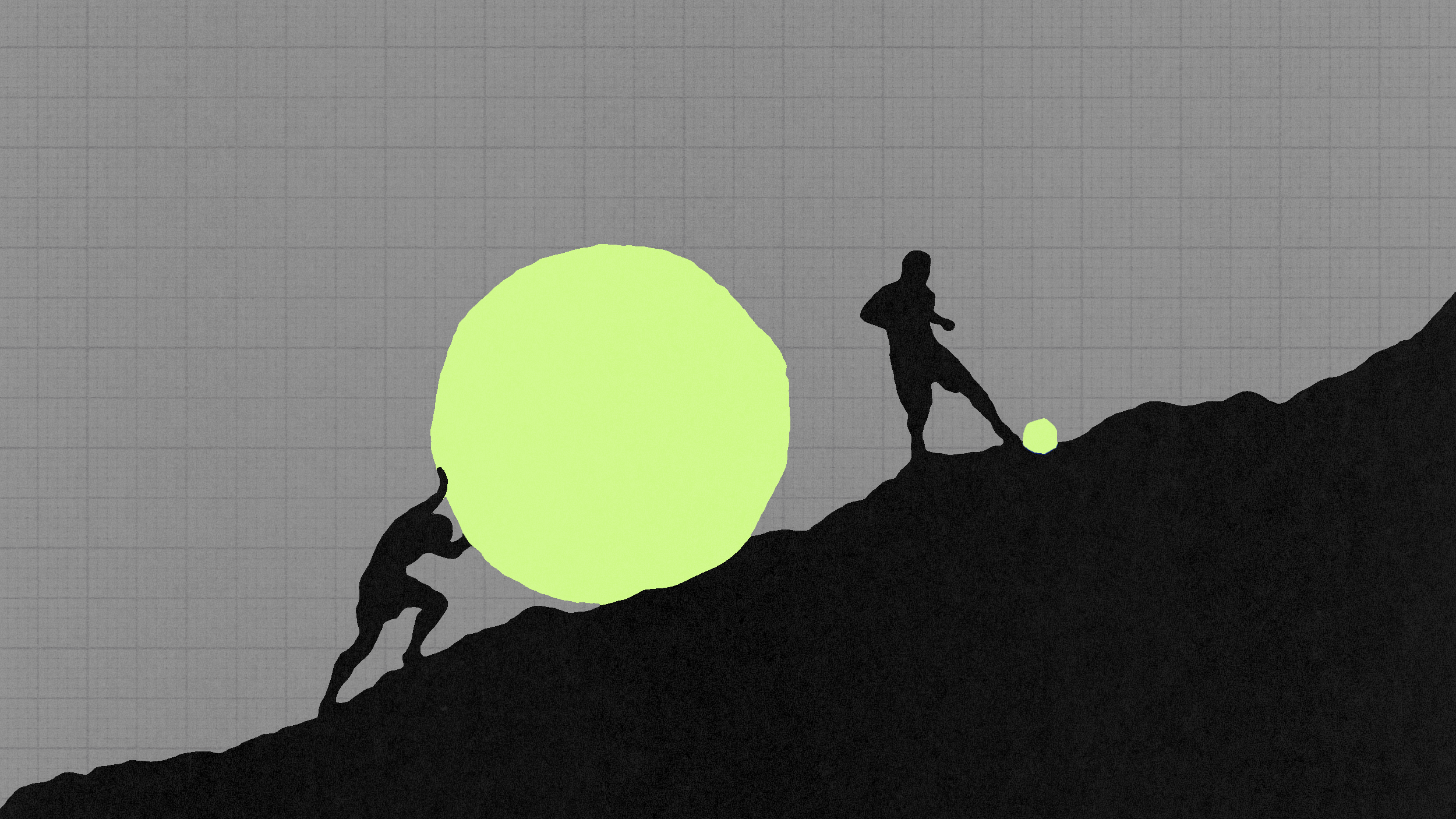

So I took notice when The KIND Foundation, the creators of Kind bars, launched the Pop Your Bubble campaign. It’s a simple extension that suggests ten people on Facebook with opposing ideologies. You can choose to follow them, if you’re so inclined, with the hopes of skewing your feed in another direction.

I’m always wary of companies launching campaigns, so I’m not going to vouch for the actors in the video, or whether or not they’re really actors. Kind has long relied on “every person” marketing, which I’m not criticizing; the company’s messages have always been unifying and culturally progressive, which feeds into my bubble. Since I don’t eat their bars—I wish they would be as wary about sugar as the people eating their candy bars—I have no investment in their product.

The video does show how many of us perceive our supposed open-mindedness, however. Data always trump anecdotes, and I’m sure if most of us saw our own chart we’d be surprised how far in one direction we lean. Which begs the question, does introducing conflicting opinions help?

I added the extension to find out. Unfortunately the first ten suggestions were not exactly conflicting: a surfer who posts about environmentalism; an indigenous woman who repeatedly calls for equal rights; another writer posting about literature and restaurants. All ten were people I’d probably be friends with and certainly agree with. Well, nine: one was a florist who used their account as a business portal, though I certainly have nothing against bouquets.

Nearly a year ago I wrote an article about why unfriending is immature. It ended up one of my most popular posts in 2016, which gives me hope that people are wary of ending conversations before they’ve had the chance to begin. A number of emails and comments about that piece brought up the fact that people are stressed by what they read. I’m not convinced running into a digital safe space is a proper response to the fact that not everyone believes the same things you do, though I do agree that outright racism and bigotry can be intolerable.

Perhaps the problem is exacerbated by the medium itself. Cal Newport, author of Deep Work, does not use social media and is barely online at all, save his blog. The associate professor of computer science at Georgetown believes these distraction technologies don’t allow you to think critically about complex subjects. The more you become accustomed to quick dopamine hits provided by novelty-inducing mediums, the less likely you’re going to put in the time and effort required for sustained, nuanced thinking. This becomes especially problematic as your social media feeds become more accustomed to your likes:

They offer personalized information arriving on an unpredictable intermittent schedule—making them massively addictive and therefore capable of severely damaging your attempts to schedule and succeed with any act of concentration.

It’s easy to understand how an impatient social media surfer will immediately lash out at any perceived transgression to their moral views. This lack of depth does not have a political “side,” either. Liberals and conservatives are equally likely to scan a headline, make an assumption, and then attack (or at least formulate one in their head) without reading the entirety of what’s being discussed.

This has led me to install one simple rule regarding my own online habits: I don’t post or comment on anything I haven’t read. If an article appears on my feed, it’s been consumed. If I reply to someone about what they posted, I gave it my time before hitting enter. I’ve read too many comments on my posts asking questions that were answered in the article itself. But, as stated, the medium doesn’t allow for deep thinking, and many of us have quick trigger fingers.

Perhaps that needs to be addressed before we discuss “sides.” It’s like someone who wants to write a book but never reads. They want “their story” to be heard yet have no time to listen to others. Maybe the bubble to be popped is our own sense of self-importance. Listening is a valuable first step. Tuning down the noise in our heads to make space for others to enter might not change our overarching problem, but it is a start.

—

Derek’s next book, Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health, will be published on 7/4/17 by Carrel/Skyhorse Publishing. He is based in Los Angeles. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.