An American Idea: The Separation of Church and State

“Whereas Almighty God hath created the mind free; that all attempts to influence it by temporal punishment or burdens, or by civil incapacitations, tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness, and are a departure from the plan of the Holy author of our religion, who being Lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate it by coercions on either, as was his Almighty power to do .”

-Thomas Jefferson’s opening lines to the Virginia Statue for Religious Freedom, 1786

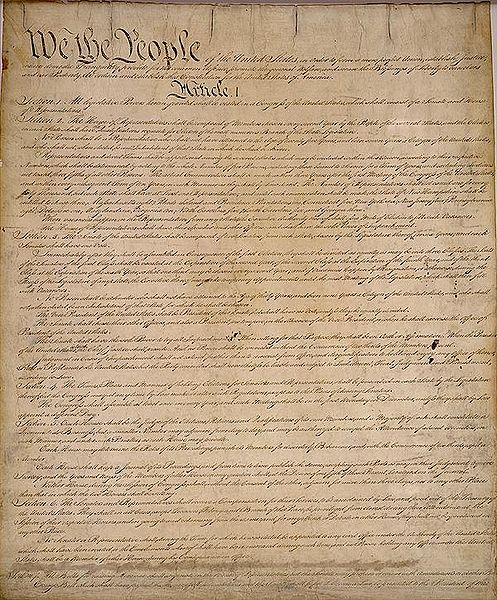

The lines above are from the document that would set the precedent for the religious freedom guarantees in The First Amendment. They also represent the first legally binding protection against tithes and and the legislation of religious prohibitions and the other trappings of that most wicked and un-American brand of dictatorship, theocracy.

It is easy to forget from the perspective of today’s political climate that the argument for “a wall between church and state” was originally supported by the religious, rather than against them.

Jefferson had first hand experience, from his political career in Virginia, of results of the dissenting views of Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians. He was not merely guessing at the pernicious effects of religion on government, and vice versa.

The idea of one “Christianity” is a modern conceit, and it was widely understood by religious sects of Jefferson’s time that each differing religion necessarily implied something that Stephen Colbert once expressed with characteristic panache: “It is a part of my religion that your religion is wrong.”

Habits of hypocrisy and meanness indeed.

The beauty of the separation of church and state is really best encapsulated in its original formulation; in The Virginia Statute, Jefferson argues not against religion, but, rather, for humanity. He uses reasoning that parallels some of Christianity’s nicer claims, based largely on his own Deism.

He forcefully asserts the truth of his claim that government-sponsored religion is wrong, while also leading by example: He allows for the possibility of future repeal of this manifestly good law because he does not wish to lay down dogmatic prescriptions. To do that would be to embrace the very power which he wishes to deny.

The free will of man, and the ability to express that free will both individually and to collectively legitimize a government, was to Jefferson an inarguable fact of life. It is no wonder, then, that he ended The Statute with these words: “we are free to declare, and do declare, that the rights hereby asserted are of the natural rights of mankind, and that if any act shall be hereafter passed to repeal the present, or to narrow its operation, such as would be an infringement of natural right.”

If we wish to argue that America was truly founded on the principles of The Enlightenment, then this is surely our finest evidence.