Chicago 50 years later: a city looks back and disagrees on what happened

1968 was a tough year for the United States and the rest of the world. Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. were assassinated, Czechoslovakia tried to break free from Russian domination, the Vietnam war dragged on, French youth and blue-collar workers rose against the government, the Cultural Revolution carried on in China, and unrest raged on in every major nation on Earth.

Perhaps one of the most memorable events in that year were the riots in Chicago during the Democratic National convention which saw peace protesters, countercultural leaders, the Yippies, SDS, and more than a few people there for kicks beaten by policemen trying to keep order in the streets while the Democratic Party struggled in the International Amphitheatre.

It was, perhaps, the entire year compressed into a single event. The forces of youth raging against the establishment while that establishment tried to carry on with the same activity that caused the rage in the first place.

So much tear gas was used by the Chicago Police that Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic Nominee for president, was made sick in his hotel room. The whole world was watching, and several political careers would be influenced by it. So horrifying were the images on the TV screens that it was said that this was “the night America voted for Richard Nixon.”

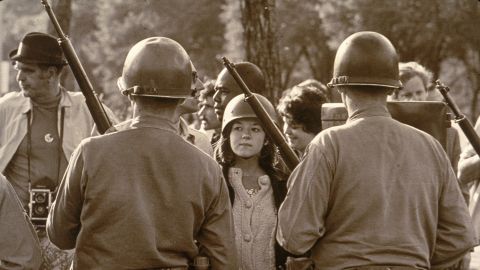

For those of you who haven’t seen the images, here is a video of what was later called the “police riot.”

But, as a city looks back on the 50th anniversary of the events, differing recollections suggest we haven’t even decided what it was about.

On the fiftieth anniversary of the start of the convention, a panel discussion was held about the events of late August 1968. It featured such names as the Chicago Alderman Ed Burke, former Alderman and professor Dick Simpson, Professor Bernie Sieracki and newspaper reporter and author Taylor Pensoneau; all of whom were at the convention or the riot in some capacity.

The event took place in the auditorium of the illustrious Harold Washington Library in downtown Chicago, a mere half mile from where the riots took place.

Professor Sieracki was a student at the time. He was not directly involved in any of the events but saw a great deal of the events by happening to be downtown.

He argued that the riots were caused in part by “lunatics” who had no intention of making progress that day. Mentioning the application submitted to the city by the Yippies for a festival in the park; he pointed out that the various requests, including one for non-enforcement of drug laws, were designed to be rejected.

He claimed that bags of excrement were thrown at the police by some protesters[i] and that the taunts and threats of harm would have been too much to bear for most people.

Professor Simpson, who was a Eugene McCarthy volunteer, saw The Battle of Michigan Avenue as a clash between the forces of old and new. A fight between people who held radically different views of society squaring off in the streets after the Democratic Primary, which was controlled by party insiders, prevented a meaningful clash from occurring inside the convention hall.

He recalled that he and his wife took the L-train down to the station nearest the rioting to help, but were prevented from getting closer by policemen and barbed wire. He mentions participating in the peaceful marches the day before in his autobiography.

He mused that the same battles which were fought in ’68, ones for peace, changes to the primary system, racial equality, the structure of society, and the eternal issue of law and order versus utopian ideas of a new world remain unsettled.

Alderman Burke was a plainclothes policeman in the convention hall. He recalled that the events of the convention are often misremembered, and testified that Daley didn’t say the racial slurs he is often accused of[ii] towards Senator Ribicoff.

He also, however, claimed that Dan Rather was the aggressor in the famous scuffle where he was manhandled by security on the convention floor and that Rather admitted as much, and that the authors of the Walker Report, who coined the term “police riot” to describe the events on Michigan Ave, later regretted the use of the word[iii].

Reporter Taylor Pensoneau was assigned to cover the convention and found himself having to go in and out of the Conrad Hilton hotel downtown frequently. He saw the rioting first hand and claimed to have been shoved into poet Allen Ginsberg during a struggle.

Recalling the horrors downtown during the riots, he explained the utter chaos in the streets. He described seeing a protester beaten by several policemen on one street while on the next the youths got the better of the policemen, chasing them up the street with truncheons in their hands.

He related the sight of the national guard following orders while a group of policemen broke ranks and rioted. He confirmed a few stories of protesters purposely trying to provoke the officers.

They all agreed, for the most part, that the events are often misremembered and that both sides shared blame for the riot. They further suggested that many protesters were strictly there as troublemakers without real interest in working for the cause of peace. The narrative remained the same for all of them; they differed only in details.

Things got out of control in a hurry, what started with peaceful protests and the nomination of a pig for president ended up in riots. Here a group of protesters tries to tip over a paddywagon. (APA/Getty Images)

But in a smaller venue, the stories changed.

A few days previously, a small discussion about the life of a Chicago-based activist had taken place on the North Side. I found myself in the cramped office it was shoved into by happenstance. Before the discussion began, aged locals recalled where they were during the convention; many of them remembered being at Grant Park, where the protests were centered.

Not one of them regretted it, several of them proudly pointed out where they were in pictures taken during the event, and none of them mentioned anything about throwing bags of waste at the riotous policemen. For at the least the people I heard and spoke to, nobody went there to cause trouble for the sake of it. They all went to fight against a war they detested, they said. They left no doubt that they’d go again in an instant.

As Chicago looks back to a darker moment in its history and disagrees about what happened, why, and what it meant, the same questions which plagued the late sixties loom over us today. As we try to edify ourselves for the future by looking to the past, we find conflicting narratives, stories, and recollections about who threw what getting in the way.

It all brings to mind a quote by poet William Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” It sure isn’t in Chicago.

[i] I have seen contradictory evidence on if this occurred or not. The panel couldn’t agree either.

[ii] Mr. Pensoneau also supported this.

[iii] I can find nothing to support either of these statements, the second one was all but refuted by Mr. Pensoneau; who the moderator turned to for confirmation as soon as it was mentioned.