It Takes Two

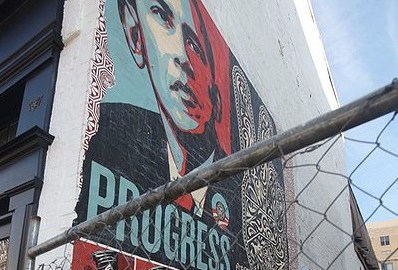

President Obama won office in part on the strength of his promise to be a “post-partisan” president. But Obama’s attempts to reach out to the other party—as admirable as they may seem in theory—may have backfired on him and the Democrats. The Republicans quickly realized that he couldn’t change the tenor of politics on his own. And if they didn’t meet him halfway, he would be unable to make good on his promise.

It takes two to cooperate, after all. And the Republican strategy has been to attack every Democratic proposal—regardless of what it is—as so radical that no compromise is possible. Again and again, the Republicans have portrayed President Obama as governing from the far left, when, as I’ve argued, he hasn’t actually been particularly liberal. They’ve even called proposals they themselves originally came up with “socialist.” The idea was both to create the impression the Democrats were steamrolling them and to make it difficult for Democrats to accomplish anything of substance. It’s not that the Republicans don’t have substantive differences with the Democrats or that they haven’t been frozen out of some aspects of the legislative process. But the plain fact is that the Democrats have made every effort to win Republican votes in Congress. And on issue after issue, they were unable to win a single one.

The truth is that much of the legislation before Congress is, as David Leonhardt says, “politically partisan and substantively bipartisan.” Consider health care. The vote in the Senate was split strictly along partisan lines, with all 40 Republicans voting against it and the entire Democratic caucus voting for it. But, as Leonhardt argues, the supposedly radical Senate bill is actually more conservative than either Bill Clinton or Richard Nixon’s plans. In fact, the Senate bill incorporates both Republican and Democratic ideas, and is effectively the product of sixty years of negotiation between the two parties. Controversial liberal proposals such as the one for a government-run health care plan have been completely removed from the bill. As Nate Silver says, the bill is “about the least radical way to achieve something approaching universal coverage that can be imagined.”

With substantial majorities in both houses of Congress, of course, the Democrats don’t need Republican cooperation. Part of their problem has been that the Democratic Party is internally divided on important policy issues, making it difficult for them to force legislation through Congress, even with their sizable majority. But another part of their problem is that they have been so focused on courting the center they have been unwilling to play the hardball the Republicans accuse them of playing. If the Democrats are going to accused of being partisan anyway, however, they might as well start really being partisan.

That doesn’t mean the Democrats shouldn’t be willing to compromise with any Republican willing to cross party lines. But if the Republicans are going to do their best to shut down the government, the Democrats are going to have to govern without them. Let the Republicans protest, since they’re going to do it anyway. Dare them to try to shut Congress down. Force them to vote against cloture, again and again and again. And, when they do, make sure the whole country sees. The Republicans certainly aren’t going to help the Democrats get anything through Congress. And no concession short of complete capitulation is likely to win any Republican votes. If the Democrats are going to get anything done, they’re going to have to do it themselves.