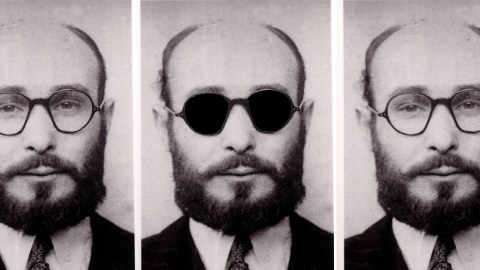

Juan Pujol Garcia: The WWII double agent who secretly controlled the war

Juan Pujol Garcia was instrumental in ensuring the success of the Allied invasion of Europe on D Day and, by extension, the Allied victory of the Second World War. But his actions during the war aren’t widely known. Despite being a little-known figure in history, Garcia is one of the few, if not the only, individuals in the war to receive both an Iron Cross from Hitler and an MBE (a Member of the Order of the British Empire) from King George VI. His lack of fame might seem unjust, but a famous spy is kind of an oxymoron.

Arguably, Garcia would become one of the most important figures in World War II, but prior to the war, he hadn’t amounted to much in his life. Mostly, he was a chicken farmer in Spain. He tried and failed to run a variety of businesses, including a managing a cinema. When the Spanish Civil War broke out, he deserted the Republican army to join the Nationalists, only to be imprisoned when he expressed sympathy for the monarchy.

When World War II broke out, he was running a dumpy, one-star hotel in Madrid. He had been a mediocre soldier and had admitted he was ill-suited to warfare; so his motives for approaching the British to offer his services are unclear. The British seemed to think that a military deserter, ex-chicken farmer, and failed businessman would not be of much use in the war and turned him away. However, Garcia was determined to participate in the war, and he would repeat his request to the British on three separate instances, only to be refused each time.

A self-made spy

In what might be one of history’s greatest examples of unearned confidence, Garcia decided that in order to build a resume as a spy, he should gain the trust of the Nazis and feed them misinformation from within. At that time, the Spanish government was sympathetic to but unallied with the Nazi government, and it was easy to make contact with the German army.

He tricked a printer in Portugal into thinking he was a Spanish government official working at the local embassy and obtained a diplomatic visa, which he used to bolster a false identity as a Nazi supporter who regularly traveled to London on diplomatic business. Considering that Garcia spoke no English, this was a particularly bold lie.

The Nazis, however, bought Garcia’s fabrication. They provided him with a crash course in spycraft, gave him £600 (equivalent to around $42,000 US today), and sent him on his way to London to recruit a network of spies. Without any English skills and with a fake passport, Garcia went to Lisbon, Portugal, instead.

Garcia had gotten what he wanted. He had gained the trust of the Nazis and was in contact with them. But now he had to supply them with misinformation. By combining publicly available information from newsreels, magazines, and tourists guides, Garcia fabricated seemingly realistic reports of life in London and British activities, ostensibly fabricated by an entirely fictional spy network he had accumulated in London. These reports weren’t perfect, of course: at one point, he described how Glaswegians would do “ anything for a litre of wine,” which is very much not the Scottish beverage of choice.

Despite all of this, his mocked-up reports were widely believed. They were so thoroughly believed that the British, upon intercepting the reports, launched a nationwide manhunt for the spy who had infiltrated their country. At the time, there were supposed to be no Axis spies in Britain, so this was very disconcerting news for the Allies.

Gaining the trust of the Allies

The trick that made the British believe in Garcia’s value as a spy occurred when he invented an entirely fictional British armada in Malta that the Axis responded to in full force. Despite the nonexistence of an armada, the Nazis continued to trust Garcia’s information. With his bona fides established, Garcia was finally able to convince the British of his value in 1942.

Working with British intelligence, Garcia invented 27 fictional sub-agents from whom he attributed the various pieces of intel that he cobbled together into coded, handwritten reports he sent to the Germans and later over the radio.

Garcia’s reports consisted of a mixture of misinformation; true but useless information; and true, high-value information that always arrived too late. For instance, he provided accurate information on Allied forces landing in North Africa in a letter postmarked before the landings but delivered afterwards. The Nazis apologized to Garcia for failing to act on his wonderful intelligence in time.

To account for why he failed to provide key information he would ostensibly have access to, Garcia needed to fabricate a variety of different excuses. When he failed to report on a major movement of the British fleet, Garcia informed his Nazi counterparts that his relevant sub-agent had fallen ill and later died. Bolstered by a fictional obituary in British papers, the Nazis were obliged to provide the fictional man’s fictional widow a very factual pension. To support Garcia’s spy network, the Nazis were paying him $340,000 US (close to $6 million today).

Exploiting the Nazis

Garcia’s greatest moment came to during Operation Overlord, which began during the invasion at Normandy on D Day. Having built up trust with the Nazis over the course of the war, Operation Overlord represented the opportunity to exploit that trust.

Through a flurry of reports, Garcia convinced German High Command that an invasion would take place at the Strait of Dover (which Hitler believed to be the case anyhow). In order to maintain his credibility, Garcia told the Nazis to wait for a high-priority message at 3 AM: this was designed to provide the Germans with information on the actual target, Normandy, but just a little too late to prevent the invasion.

In a stroke of luck, the Nazis missed the 3 AM appointment and didn’t respond until later that morning. Garcia chastised his handlers for missing the critical first message, saying “I cannot accept excuses or negligence. Were it not for my ideals, I would abandon the work.”

With this extra layer of credibility, Garcia invented a fictional army—the First U.S. Army Group—led by General Patton himself and consisting of 150,000 men. With a combination of fake radio chatter and—no joke—inflatable tanks, German High Command was convinced of the presence of an army stationed in south Britain. Garcia convinced the Nazis that this was the true invasion and that Normandy was a diversion. Two Nazi armored divisions and 19 infantry divisions were withheld at the Strait of Dover in anticipation of another attack, allowing the invading force from Normandy to establish a stronger position in France. Without these extra troops, the Axis failed to beat back the Allied invasion.

By inventing a fake army and controlling the flow of information to the Nazis, Garcia ranks among one of the most influential figures of the war. His identity as a double agent was never revealed until decades after, which might explain why so little is heard of him. To be safe, he faked his death from malaria in 1949 and moved to Venezuela to run a bookshop.