Elon Musk quietly plans to put 11,925 satellites into orbit

If you blink, you could easily miss one of Elon Musk’s many SpaceX projects. The man has so many plates in the air, it’s a wonder they don’t all come crashing down. Which is the last thing you’d want with his little-noticed Starlink plan, an audacious attempt to bring high-speed internet access to the entire world by launching 11,925 satellites into orbit. That represents a nearly seven-fold increase over the estimated 1,738 active satellites currently aloft. The first two Starlink craft will be launched by SpaceX this Saturday, February 17.

Interestingly, as hard as it is to keep anything related to Musk quiet, he and SpaceX haven’t exactly been going out of their way to publicize Starlink beyond the initial announcement in 2015. When asked about the project during a Falcon Heavy press conference, Musk deflected the question: “Off topic. Today’s topic is Falcon Heavy.” One person who does know about it is FCC chair Ajit Pai, who has just endorsed the project, with the FCC having signed off in November 2017 on its upcoming first test deployment.

Elon Musk at Falcon Heavy press conference (Photo: Brendan Smialowski)

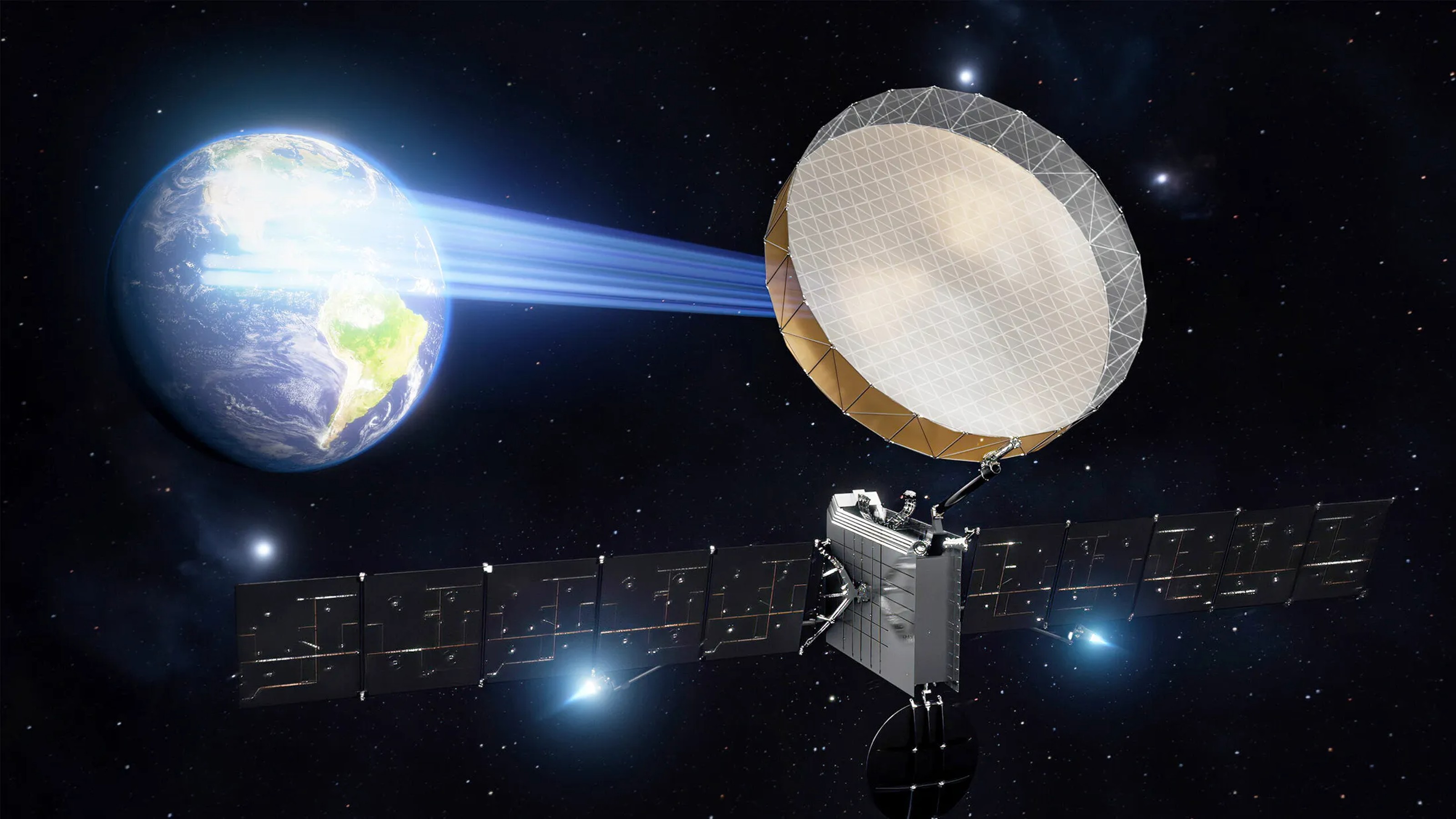

What Musk has in mind is ubiquitous high-speed, one-gigabit internet connectivity for the entire world, delivered via a network of interconnected satellites, low-cost ground stations, and roof-mounted user terminals costing $100 to $300 each. In her November testimony, SpaceX’s Patricia Cooper spoke about how all this hardware will work together: “For the end consumer, SpaceX user terminals—essentially, a small flat panel, roughly the size of a laptop—will use similar phased array technologies to allow for highly directive, steered antenna beams that track the system’s low-Earth orbit satellites. In space, the satellites will communicate with each other using optical inter-satellite links, in effect creating a ‘mesh network’ flying overhead that will enable seamless network management and continuity of service.”

Musk believes there are billions and billions of dollars to be made by being the world’s preeminent, and first, high-speed provider. When he first revealed the project in 2015 during a visit to Seattle—Starlink HQ is being developed in nearby Redmond—Musk said the system could provide low-cost broadband around the world, and that revenues from Starlink could help finance SpaceX’s Mars settlements. “The focus is going to be on creating a global communications system,” said Musk, admitting, “This is quite an ambitious effort. We’re really talking about something which is, in the long term, like rebuilding the Internet in space.”

In addition to internet service, when SpaceX applied for the Starlink trademark in August 2017, it added providing “satellite photography services” and “remote sensing services, namely, aerial surveying through the use of satellites” to its goals.

The FCC is the authorizing body for U.S. satellite launches, and much of what we know comes from SpaceX’s filing for permission from the FCC to launch 4,425 broadband and linked satellites orbiting between 715 miles and 790 miles above Earth’s surface. The plan also calls for another 7,500 satellites in lower orbit eventually.

The satellites themselves are smaller than current multi-ton telecom craft. Each will be about the size of a MINI Cooper and will weigh about 850 pounds. According to SpaceX, a Starlink satellite will be able to cover an area about 1,300 miles wide, or roughly the distance from Maine to Florida.

The first group of 4,425 satellites will be deployed in two phases. SpaceX says that once half of the first 16,000 are in orbit, the company will be able to “provide widespread U.S. and international coverage for broadband services.” After that, the launch of another 2,825 satellites will complete phase one. The entire system will have to be in place before one-gigabit connectivity is available everywhere. That would be worth waiting for, though, as a huge leap in speed from the current average of 5.1 Mbps per second. Even more important would be the delivery of internet connectivity to countless places where technical challenges currently make such services too costly, or impossible. In his recent endorsement of the entire Starlink initiative, Pai said, “Satellite technology can help reach Americans who live in rural or hard-to-serve places where fiber optic cables and cell towers do not reach.”

Of course, Pai’s concern is primarily with the U.S., but the network will range far beyond our boundaries, which raises an interesting consideration: Should other nations have a say in the deployment of so many satellites overhead, or even share in the revenue they generate? Who owns Earth’s orbit, anyway?

Once launched, the Starlink satellites will join currently active satellites and about 500,000 pieces of space junk including older, non-functional craft, as well as debris. Musk was asked about this at the 2015 announcement, and responded, “I wouldn’t worry too much about the space junk thing… We’re talking about something about the 1100 km level and there’s just not a lot up there… we’re going to make sure that we can deal with the satellites effectively and have them burn up on reentry and have the debris kind of land in the Pacific somewhere.”

Saturday, Feb. 17 2018 will see the launch of the first two Starlink satellites, Microsat-2a and Microsat-2b, from California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9. They’ll tag along on the rocket’s main mission of launching Spanish radar satellite Paz into orbit.