The Problem of the Guantanamo Detainees

The Obama administration is finally getting serious about closing Guantanamo. The main obstacle to closing the military prison has always been that it wasn’t clear where to put the approximately 200 detainees still being held there. But now the administration has floated the possibility that it might move them to American soil. Last week, a delegation from the U.S. Bureau of Prisons inspected a state-of-the-art maximum security prison in Thomson, Illinois, a depressed town of 600 near the Iowa border. The $145 million dollar facility was supposed to bring hundreds of jobs to the area, but in part because of changing Illinois correctional policies has remained largely empty. According to the administration, transferring Guantanamo detainees to Thomson could generate as many as 3200 jobs, and bring a $1 billion to the area over the next four years. Governor Pat Quinn—a Democrat, who is running for reelection next year—has planned a three-city tour to sell the idea, calling the prospect of housing prisoners from Guantanamo a “great, great opportunity for our state.”

But the idea is political dynamite. While some Thomson residents would be happy to take the detainees if it meant new jobs, it will be easy to accuse anyone who supports the proposal of wanting to “bring terrorists to Illinois.” Illinois Rep. Mark Kirk, a candidate for the U.S. Senate, has already drafted a letter to Obama, telling him that “terrorists should stay where they cannot endanger American citizens” and saying that if the administration “brings Al Qaeda terrorists to Illinois, our state and the Chicago Metropolitan Area will become ground zero for jihadist terrorist plots, recruitment and radicalization.”

It is not clear exactly what danger the detainees would pose. In spite of the Bush administration’s repeated assertions that they are “the worst of the worst,” many are accused of things like having done “media relations” for or provided “material support” to terrorists. Even those with real operational involvement with terrorist organizations are hardly comic-book supercriminals—they certainly aren’t going to break out of prison and single-handedly blow up public buildings. If they were somehow to escape, the danger would be that they might return to work with with a terrorist group. But even then it’s doubtful that any one of them would individually pose that much of a threat. As Sen. Dick Durbin (D-IL) points out, there are already several hundred people in U.S. prisons who have been convicted of terrorism, including 35 in Illinois.

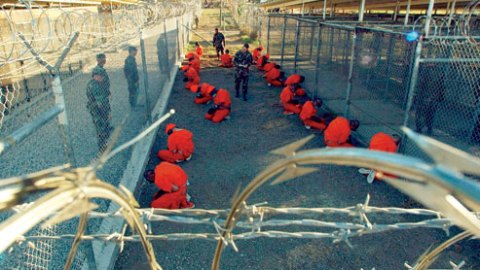

What the facilities at Guantanamo really offer is a place where we can keep our detention program out of sight and out of mind. They are the modern day equivalent of an oubliette—a dungeon where we can lock people up and forget about them. It has never been a question of our safety. But the uncomfortable fact is that we are still holding a several hundred people—often on the flimsiest of evidence—without charging them with any crime. Many have been tortured and held in terrible conditions, all in clear violation of both U.S. and international law. Even those who were never terrorists before may—after their experience in our detention program—want to hurt us. And their very existence is a terrible embarrassment to us. The real issue is that if we bring them into our communities—and bring them into our regular legal system—we will be forced to face up the difficult problem they represent. But that’s exactly why it’s what we have to do.