7 thought experiments that will make you question everything

- Thought experiments provide a platform to examine abstract concepts in a playful and imaginative manner.

- The best thought experiments challenge our beliefs and offer fresh perspectives on how the world operates by presenting hypothetical situations.

- These hypothetical situations are often constructed in extremes so we can see how certain ideas might play out — all without suffering any real-world repercussions.

Thought experiments are among the most important tools in the intellectual toolbox. Widely used in many disciplines, thought experiments allow for complex situations to be explored, questions to be raised, and complex ideas to be placed in an understandable context. Here are seven thought experiments in philosophy you might not have heard of, complete with explanations of what they mean and what questions they raise.

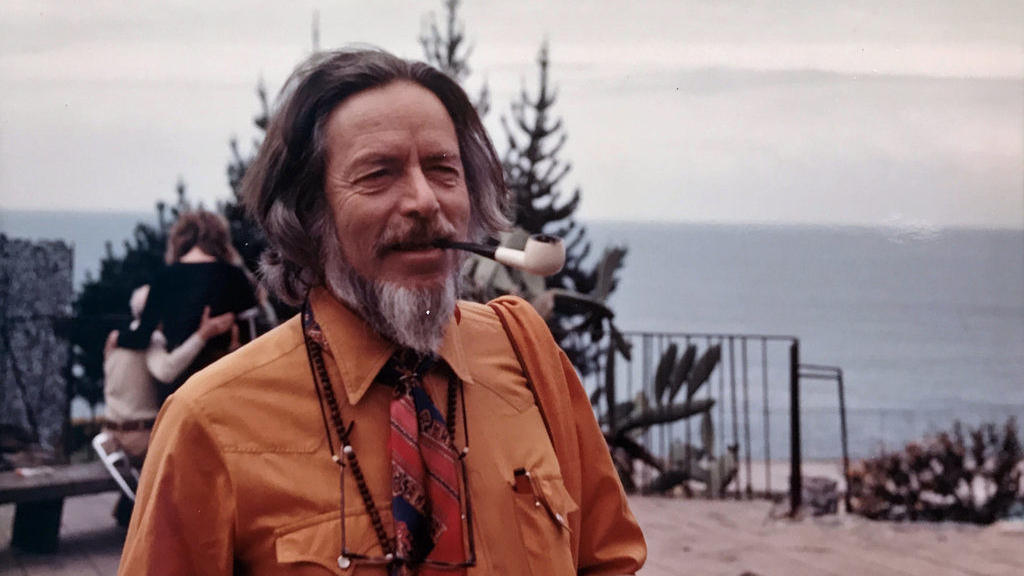

Swampman

Written by Donald Davidson in 1987, this thought experiment raises questions about identity.

Suppose a man is out for a walk one day when a bolt of lightning disintegrates him. Simultaneously, a bolt of lightning strikes a marsh and causes a bunch of molecules to spontaneously rearrange into the same pattern that constituted that man a few moments ago. This “Swampman” has an exact copy of the brain, memories, patterns of behavior as he did. It goes about its day, works, interacts with the man’s friends and is otherwise indistinguishable from him.

Question: Is the Swampman the same person as the disintegrated fellow?

Davidson said no. He argues that while they are physically identical and nobody would ever notice the difference, they don’t share a casual history and can’t be the same. For example, while the Swampman would remember the friends of the disintegrated man, it never saw them before. Another person saw them and the Swampman just has his memories.

There are objections to the idea that the two characters in the story are different. Some argue that the identical minds of Swampman and the original person mean that they are the same person. Others, like philosopher Daniel Dennett, argue that the entire experiment is too far removed from reality to be meaningful.

This raises problems for teleportation as seen on Star Trek and for those who want to download their brains into a computer. Both cases rely on one version of you being created and one disappearing, but is the second version of you still you?

Thompson’s violinist

This one was written by Judith Thomson in her 1971 essay A Defense of Abortion. She writes:

“You wake up in the morning and find yourself back to back in bed with an unconscious violinist. A famous unconscious violinist. He has been found to have a fatal kidney ailment, and the Society of Music Lovers has canvassed all the available medical records and found that you alone have the right blood type to help. They have therefore kidnapped you, and last night the violinist’s circulatory system was plugged into yours, so that your kidneys can be used to extract poisons from his blood as well as your own. If he is unplugged from you now, he will die; but in nine months he will have recovered from his ailment, and can safely be unplugged from you”

Question: Are you obligated to keep the musician alive, or do you cut him loose and let him die because you want to?

Thompson, who has several excellent thought experiments to her name, says no. Not because the violinist isn’t a person with rights, but rather because he has no right to your body and the life-preserving functions that it provides. Thompson then expands her reasoning to argue that a fetus also lacks the rights to another person’s body and can be evicted at any time.

Her argument is subtle, however. She doesn’t say you have a right to kill him, only to stop him from using your body to stay alive. His resultant death is viewed as a separate, yet related, event that you have no obligation to prevent.

The Veil of Ignorance

This experiment was devised by John Rawls in 1971 to explore notions of justice in his book A Theory of Justice.

Suppose that you and a group of people had to decide on the principles that would establish a new society. However, none of you know anything about who you will be in that society. Elements such as your race, income level, sex, gender, religion, and personal preferences are all unknown to you. After you decide on those principles, you will then be turned out into the society you established.

Question: How would that society turn out? What does that mean for our society now?

Rawls argues that in this situation we can’t know what our self-interest is so we cannot pursue it. Without that guidepost, he suggests that we would all try to create a fair society with equal rights and economic security for the poor both out of moral considerations and as a means to secure the best possible worst-case scenario for us when we step outside that veil. Others disagree, arguing that we would seek only to maximize our freedom or assure perfect equality

This raises questions for the current state of our society, as it suggests we allow self-interest to get in the way of progressing towards a just society. Rawls’ ideas about the just society are fascinating and can be delved into here.

The Experience Machine

Robert Nozick came up with this thought experiment, which appears in his book Anarchy, State, and Utopia.

Imagine that super neuroscientists have created a machine that can simulate pleasurable experiences for the rest of your life. The simulation is ultra-realistic and indistinguishable from reality. There are no adverse side effects, and specific pleasurable experiences can even be programmed into the simulation. Regarding pleasure experienced, the machine offers more than is possible in several lifetimes.

Question: Do we have any reason to not go in?

Nozick argues that if we have any reason to not get in then hedonistic utilitarianism, the idea that pleasure is the only good and that we ought to maximize it, is false. Many people value having real experiences or being a person who does things rather than dreams about doing them. No matter what the reason, if you don’t go in you can’t claim pleasure is the only good, and Nozick thinks most people won’t go in.

There are counter-arguments, however. Some hedonists argue that people really would go into the machine or that we have a status quo bias that leads us to treat the reality we are currently in as more important than other, better ones. In either case, the experiment does present us with a problem for those who argue we only want pleasure.

Mary’s Room

In 1982, philosopher Frank Jackson proposed this thought experiment that raises questions about the nature of knowledge.

Mary lives in a black and white room, reads black and white books, and uses screens that only display images in black and white to learn everything that has ever been discovered about color vision in physics and biology. One day, her computer screen breaks and displays the color red. For the first time, she sees color.

Question: Does she learn anything new?

If she does, then it shows that qualia, individual occurrences of subjective elements of experience, exist; as she had access to all possible information other than experience before she saw the color but still learned something new.

This has implications for what knowledge and mental states are. Because if she learns something new then mental states, like seeing color, can’t be described entirely by physical facts. There would have to be more to it, something subjective and dependent on experience.

If she doesn’t learn anything new, then we would have to apply the idea that knowing physical facts is identical to experiencing something everywhere. For example, we would have to say that knowing all about echolocation is similar to knowing what it is like to use it.

This experiment is unique of the ones on this list as the author later changed their mind and argued that Mary seeing red doesn’t count as evidence that qualia exist. However, the problems posed by the experiment remain widely debated.

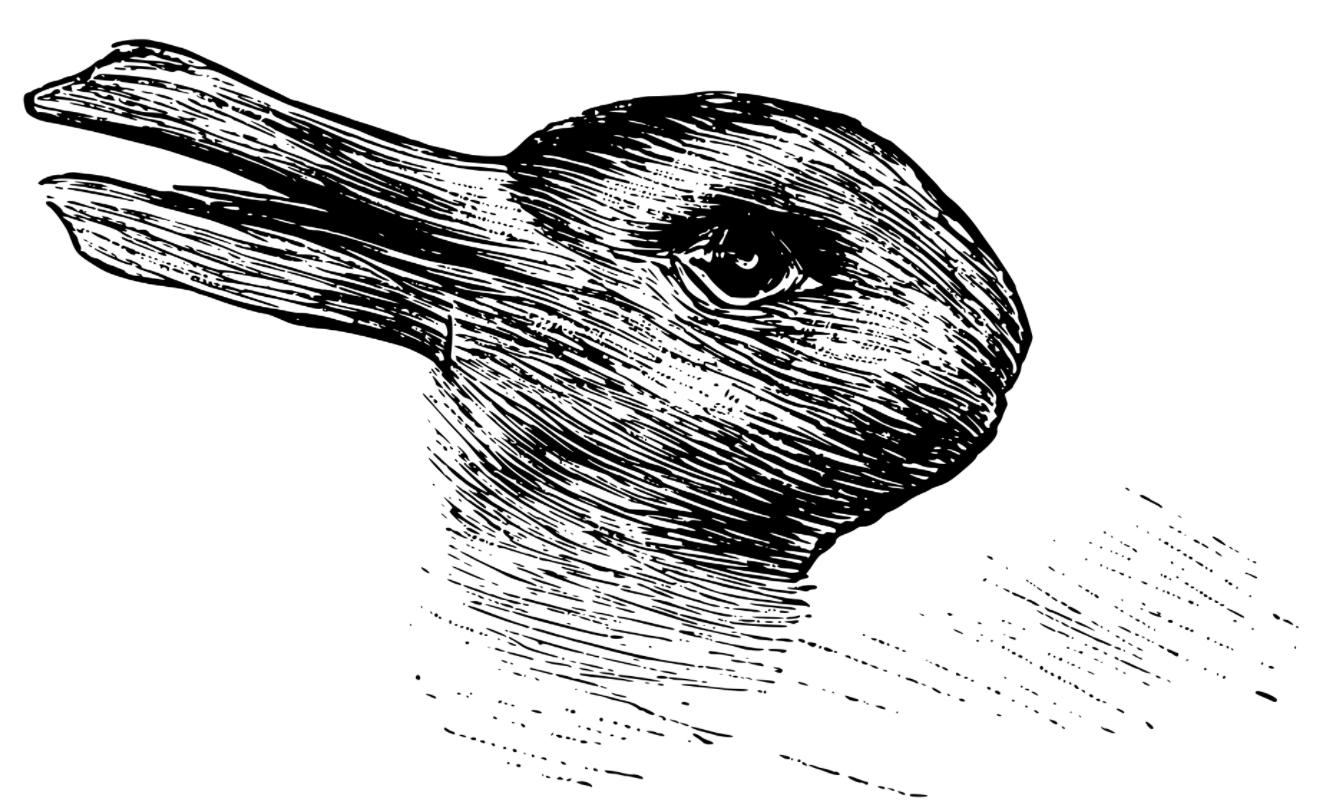

Buridan’s Ass

Variations on this experiment date back to antiquity, this formulation was named after the philosopher Jean Buridan, whose views on determinism it ridicules.

Imagine a donkey placed precisely between two identical bales of hay. The donkey has no free will, and always acts in the most rational manner. However, as both bales are equidistant from the donkey and offer the same nourishment, neither choice is better than the other.

Question: How can it choose? Does it choose at all, or does it stand still until it starves?

If choices are made based on which action is the more rational one or on other environmental factors, the ass will starve to death trying to decide on which to eat- as both options are equally rational and indistinguishable from one another. If the ass does make a choice, then the facts of the matter couldn’t be all that determined the outcome, so some element of random chance or free will may have been involved.

It poses a problem for deterministic theories as it does seem absurd to suppose that the ass would stand still forever. Determinists remain split on the problem that the ass poses. Spinoza famously dismissed it while others accept that the donkey would starve to death. Others argue that there is always some element of a choice that differentiates it from another one.

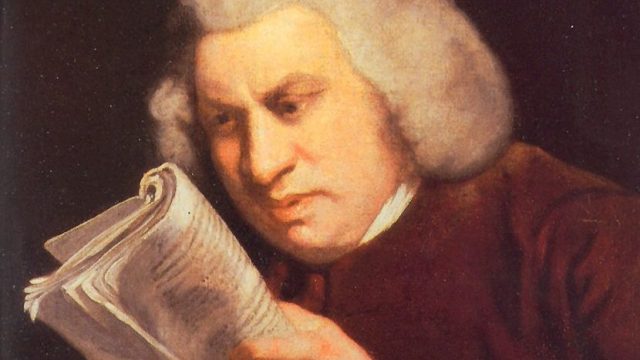

The life you can save

This experiment was written by famed utilitarian thinker Peter Singer in 2009.

Imagine that you are walking down the street and notice a child drowning in a lake. You can swim and are close enough to save her if you act immediately. However, doing so ruins your expensive shoes. Do you still have an obligation to save the child?

Singer says yes, you have a responsibility to save the life of a dying child and price is no object. If you agree with him, it leads to his question.

Question: If you are obligated to save the life of a child in need, is there a fundamental difference between saving a child in front of you and one on the other side of the world?

In The Life You Can Save, Singer argues that there is no moral difference between a child drowning in front of you and one starving in some far off land. The cost of the ruined shoes in the experiment is analogous to the cost of a donation, and if the value of the shoes is irrelevant than the price of charity is too. If you would save the nearby child, he reasons, you have to save the distant one too. He put his money where his mouth is, and started a program to help people donate to charities that do the most good.

There are counter-arguments of course. Most of them rely on the idea that a drowning child is in a different sort of situation than a child who is starving and that they require different solutions which impose different obligations.