Peter Singer explains why he helped create the “Journal of Controversial Ideas,” a platform for discussing and examining controversial topics without fear of backlash or censorship.

According to Singer, history is rife with examples of people challenging beliefs that were once considered certain but were later proven false. Persecuting those people who challenged those prevailing notions, Singer says, stifled progress.

Singer underscores the importance of protecting academic freedom and freedom of thought and expression as fundamental to societal progress and knowledge advancement.

PETER SINGER: We should try to make ourselves more comfortable with controversial ideas because it's important that those ideas be discussed. We can never know for sure when we're mistaken. There've been such a lot of beliefs that people have been certain of and persecuted people who oppose them that we now regard as false.

It's quite possible that we are all agreed on things that we believe to be true, that are false, and if we prevent them being critically examined and scrutinized and prevent people putting arguments against them, we are not going to discover which of our beliefs are false and which of them are true.

I founded the "Journal of Controversial Ideas" together with my co-editors Francesca Minerva and Jeff McMahan because all three of us were troubled by the narrowing climate of ideas that could be openly and freely discussed.

When a young philosopher, Rebecca Tuvel, published an article in which she accepted the idea that people who wish to be transgender should be able to identify as a gender different from that with which they were born- but she asked the question, if people can do that with gender, why can't they do that with regard to race? She gave us an example of somebody who had not been descended from African ancestry, but was working for an organization in the United States that was helping Blacks and herself identified as Black.

And when it was exposed that she was not really Black, she lost her position and there was a lot of condemnation. And in fact, a lot of that condemnation came from people with the same politics as those who strongly supported the idea of anybody to identify as a gender different from that that they were assigned at birth.

So simply for raising that question about trans-racialism, there was a petition to the journal calling for it to be withdrawn and criticizing the editors for publishing it. It was directed against a young woman who was an untenured philosophy professor at that time.

So we felt that the article was one that raised a good question and an appropriate response for those who disagreed would've been to show why they thought it was wrong. To attack the article and say it ought to be withdrawn seemed to us to be completely the wrong reaction. And then there've been a number of other instances since then.

It seems like university administrations have been very weak in standing up to defend academic freedom. And the idea of university administrations following a Twitter storm of protest against one of their professors having said something seemed to us to be completely wrong.

And our concern was that people would stop publishing controversial ideas. So we thought it would be good to have a journal that we reviewed anonymously, so people are not biased, and then publish good articles. And if the authors did not want to put their name on it, we would accept anonymous publication.

The argument is mostly put against the controversial articles that we receive that they are going to harm disadvantaged or marginalized groups. But against that, we weigh the importance of having an open debate on issues and the importance of an issue doesn't disappear if you suppress discussion about it. People will still think these things and some people will say these things and because there is no open discussion, there won't be any good understanding of how best to refute the things that people have said.

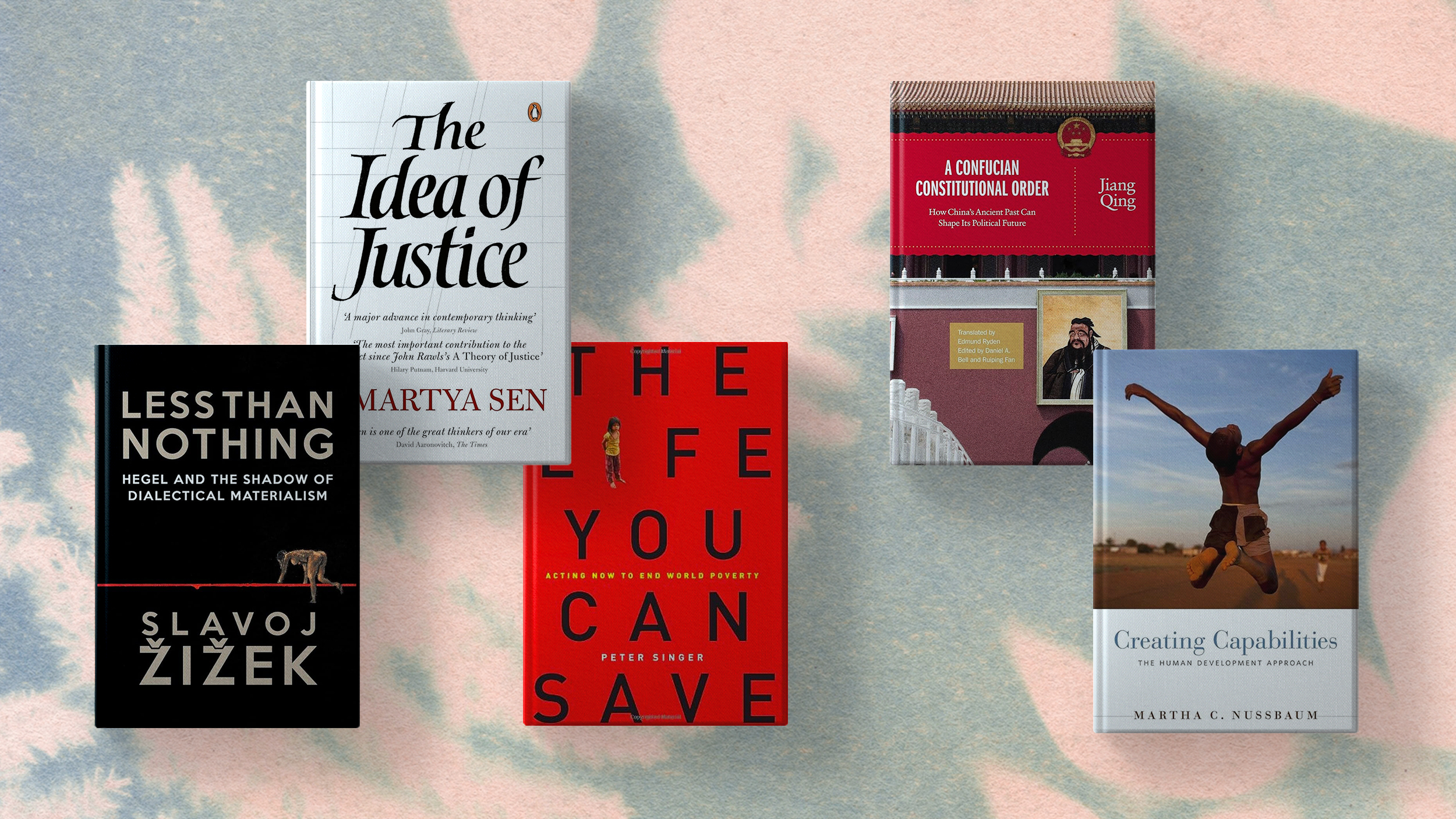

We stick by the view that John Stewart Mill put forward that: In the early 19th century, Jeremy Bentham, the founder of the Utilitarian School, wrote essays strongly attacking the idea that it should be a crime for anyone to have sex with someone of their own sex. But Bentham never published those papers because he felt that to publish them at that time would've brought discredit on all of the other things that he and the early English Utilitarians wanted to do- so those essays remained unpublished until this century.

That's an example of something that people firmly believed in and did not allow a real debate. Maybe if they had been more open to controversial ideas and they'd had debates about that, then many decades of repression and discrimination against gays could have been avoided. Freedom of thought and expression is a very important basic good for any society that hopes to progress, that hopes to improve the world's situation- and hopes also to progress in knowledge and understanding of what is true.

NARRATOR: Want to dive deeper? Become a Big Think member and join our members-only community. Watch videos early and unlock full interviews.