Sabine Hossenfelder investigates life’s big questions through the lens of physics, particularly Einstein’s theory of special relativity. She highlights the relativity of simultaneity, which states that the notion of “now” is subjective and dependent on the observer. This leads to the block universe concept, where past, present, and future all exist simultaneously, making the past just as real as the present.

Hossenfelder also emphasizes that the fundamental laws of nature preserve information rather than destroy it. Although information about a deceased person disperses, it remains an integral part of the universe. This idea of timeless existence, derived from the study of fundamental physics, offers profound spiritual insights that can be difficult to internalize in our everyday lives. As a result, Hossenfelder encourages people to trust the scientific method and accept the profound implications of these discoveries, which may reshape our understanding of life and existence.

As a physicist, Hossenfelder trusts the knowledge gained through the scientific method and acknowledges the challenge of integrating these deep insights into our daily experiences. By contemplating these profound concepts, we can potentially expand our understanding of reality and our place within it.

SABINE HOSSENFELDER: Okay, so let's talk about the physics of dead grandmothers. So I was sitting in a taxi together with a young man, and when I told him I'm a physicist, he said, "Oh, can I ask you a question about quantum mechanics?" And so I thought, "Well, okay, go ahead." And he said, "A shaman told me that my grandmother is still alive because of quantum mechanics. Is this right?"

I had to pause for a moment and try to understand, and after thinking about this for a while, I came to the conclusion it's not entirely wrong. But the thing is, it's got nothing to do with quantum mechanics. It's actually got something to do with Einstein's theory of special relativity. It's all about the reality of time. It's all about the question whether the present moment, this now, which we experience ourselves, whether this is of fundamental importance.

There are a lot of things, like those big existential questions about afterlife, that physics can actually tell us something about. My name is Sabine Hossenfelder. I'm a physicist and research fellow at the Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies, and I have a book that's called "Existential Physics: A Scientist's Guide to Life's Biggest Questions."

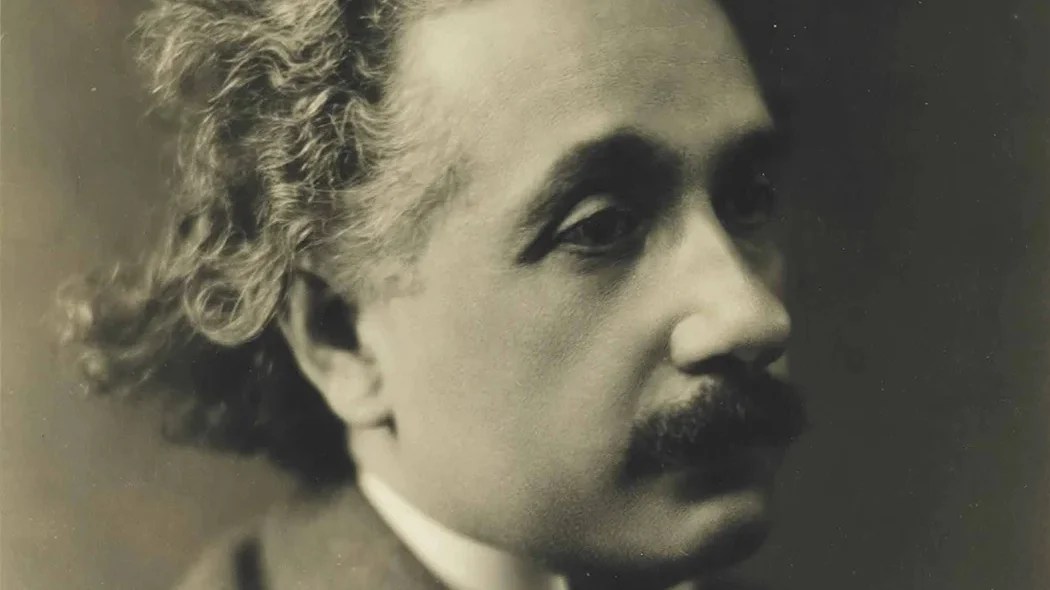

Before Einstein, time was this universal parameter. We all shared the same moment of time; the same moment of now that we could all agree on. But then Einstein came and he said, "Well, it's not that simple." And the major reason for this is that the speed of light is finite, and nothing can go faster than the speed of light- it's the same for all observers.

And this sounds like a really innocent assumption, but it has a truly fundamental consequence, which is fairly easy to understand actually. If you ask yourself whether you know if the screen in front of you is actually there right now, naively we would say, "Yes, of course it's there, I mean, I'm holding it my hand, or I see it directly in front of me." But, we just learned that the speed of light is finite, and nothing can go faster than the speed of light. So everything that you experience, everything that you see, you see it as it was a tiny little amount of time in the past. So how do you know that anything exists right now? What do you even mean by "now?" So this is the problem that comes up in Einstein's theory of special relativity.

And Einstein tried to construct a notion of "now" in this new theory, and he failed. So, imagine you're looking straight ahead, and there's a train going through to your line of sight, say, from the left to the right. And on the train, there's your friend, and let's call her Alice. Now, let's also imagine that at the exact moment that Alice, who's standing in the middle of the train, is looking straight at you, there are light flashes going off on both ends of the train. And the question is: Did these light flashes happen at the same time?

Now, if you want to answer this question looking at the train, that's pretty straightforward. There are those light flashes going off. They both come from sources that are the same distance from you. So of course you see them at the same time. But how does the same thing look from Alice's perspective? The light flashes go off, but while the light travels towards her, she's moving towards one of the light sources and away from the other, so that one path of the light is shorter and the other one is longer. So from Alice's perspective, the light flash from the front of the train arrives earlier than the one from the back. So she would say, "No, they did not happen at the same time." And now the important point is that this is relativity. Neither of them is right, and neither of them is wrong. They both have an equally valid perspective.

And what do we conclude from this? Well, we conclude from this that there is no unambiguous notion to define what happens now: It depends on the observer. So they're both right. And if you follow this logic to its conclusion, then the outcome is that every moment could be now for someone. And that includes all moments in your past, and it also includes all moments in your future. So this impossibility to define one notion of now that we all agree on is called the 'relativity of simultaneity.'

And it's super important because it tells us that fundamentally, this experience of now that we all share is meaningless. So the mathematical framework that Einstein came up with to make sense of this absence of now and the finiteness of the speed of light and the relativity of simultaneity, is that he combined space with time to one common entity, which is called spacetime. And more specifically, because the present moment has no fundamental significance, this entire spacetime exists in the present moment, and it's become known as the block universe. In the block universe, the past, the present, and the future exists in the same way. There's just no way that you can single out one particular time as special.

So, the past in which your grandma is still alive exists the same way as this present moment. Now, there's another way to look at this idea that people who have sadly deceased do in some sense still exist- and it's because of the way that all the fundamental laws of nature that we know work. They don't destroy information. The only thing that they do is that they rearrange the matter and radiation and everything that's in the Universe; they just give you the rules for how to put them in different places with different velocities. But you can apply those rules forward and backward. And this means if you had a really, really good computer, you can in principle always find out what happened earlier.

So in this sense, information cannot get destroyed. It can, however, become for practical purposes, impossible to retrieve. There are two cases that physicists have considered where information might get destroyed that have so far not been resolved: One of them is the information that falls into a black hole. We don't actually know what happens with it. And the other one is the mysterious measurement process in quantum mechanics, which is also an unresolved problem.

So if someone you knew dies, then of course we all know that you can no longer communicate with this person. And that's because the information that made up their personality, it disperses into very subtle correlations in the remains of their body, which become entangled with all the particles around them. And slowly, slowly they spread into radiation that disperses throughout the solar system, and eventually throughout the entire Universe. But this is a very anthropomorphic thing: It's very tied to our own existence, and who knows what's going to happen in a billion years or something to the nature of humans. Maybe there'll be some cosmic consciousnesses, which will also be spread out, and this information will become accessible again.

So, I know it sounds crazy, but for all we know about the fundamental laws of nature about Einstein's theories, and about the way that our current theories work, it seems that our existence actually transcends the passage of time. There is something timeless about the information that makes up us and everything else in the Universe. And I think that's a really deep spiritual insight that we get directly from studying the foundations of physics. And I have to admit that I personally find it really hard to make intuitive sense of it. It's one way to look at the maths and say, "Okay, this is how it works." These are the conclusions that we draw from our observations, and the mathematics describes it correctly. It's another thing entirely to make sense of this in your everyday life. But as a physicist, I trust the process of knowledge discovery that comes from using the scientific method, and so I take this seriously.