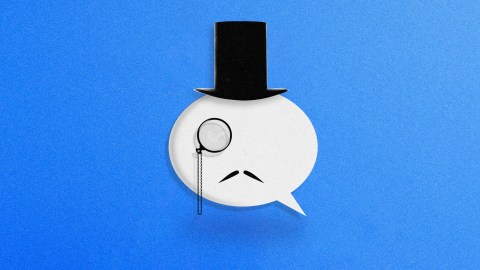

Good communicators don’t use jargon or pompous words

- In politics and business, esoteric language is often used to bury bad news or polish dull ideas.

- Translating jargon is a crucial part of a communicator’s job.

- Shakespeare was very good at creating verbs from nouns — but everyone else is annoying when they try their hand at “verbing.”

Professional jargon has a technical function. You can’t be a doctor if you don’t know the names of the parts of the body, or of the processes and diseases it undergoes. But learning the jargon is not only a way to master knowledge. It is also a way to show off — both to people inside the group (fellow doctors) and to those outside it (patients).

Take hyperemesis gravidarum, a serious condition suffered by some pregnant women. An obstetrician will explain that it involves serious nausea and uncontrolled vomiting. And the label of the disease gives the doctor’s diagnosis an air of learning. But a classicist might scoff: “hyper” merely means “super” or “a lot,” in Greek. And “emesis” means nothing more than “vomit.” Finally “gravidarum” is Latin for “of pregnancy.” If you tell your doctor, “I’m pregnant and throwing up all the time,” and your doctor replies “You have what is technically known as ‘pregnancy supervomit,'” you will not be impressed.

Such terminology puts a distance between doctor and patient, and may make the patient feel alienated from her condition and treatment. A good doctor will explain conditions like hyperemesis well. But in the main, doctors are trained to treat those conditions, and not to translate all that Greek for the patient. Your job as a writer, on the other hand, is precisely that: translation, or explanation.

Translation is even more important when politicians or businesses try to bury bad news, put a shine on mediocre ideas, or generally try to sound impressive by using terms beloved of insiders yet never once heard in casual conversation. Avoid the following pitfalls:

1. Pomposity. Meetings or conferences are dressed up as summits. Granular is edging out detailed. Brainstorming has become ideation, and at one of those ideation sessions it was decided that learnings were more valuable than lessons and optics classier than appearances. None of these improves on the older, more common word; nothing has been added except novelty.

2. Verbing. There is nothing inherently wrong with verbs formed from nouns. English is full them. Shakespeare was a master verber (“Grace me no grace, nor uncle me no uncle”). Some verbed nouns settle into the language over time: Contact and host were considered horrible as verbs not long ago. But unless you are Shakespeare you are more likely to annoy than entertain with novel verbings. It may be only a matter of time before no one is bothered by to impact or to access, but they still annoy enough readers that you should write to have an impact on or to gain access to. Similarly, find alternatives for to showcase, to source, to segue, and to target. Newer verbings are even more noxious to readers: the likes of to action, to gift, to interface, and to whiteboard should never escape the office meeting-room.

3. Misdirection. Many jargon words seem designed to obscure. When companies merge, they inevitably promise synergy — that the two partners can do more together than apart. Scratch the surface and this usually means that they can do more with fewer workers.

But then matters take their course. The company detects issues (never “problems”). These might entail a cyclical downturn (a recession, so nobody is buying their product at the moment) or a secular downturn (which means that their industry is shrinking, and people won’t buy the product tomorrow, either). Soon begins the talk of reallocation of resources, refocusing, downsizing (even rightsizing) and so on. Call these things what they are.

Most writers, especially in business, finance, economics, and science, will need to use specialized words on occasion. You should first identify those terms you will re-use often enough in your writing that they are worth keeping. They are best, in effect, taught to your reader. Explaining an unfamiliar concept in terms of a familiar one (a metaphor) is an effective way to do this.

The terms you need to define may be fewer than you think. Some examples from grammar show how you can phrase a term of art in words that everyone knows. Syntax, for example, is how words are combined into bigger units like phrases, clauses, and sentences. If you don’t plan to linger on syntax, you don’t need to use it at all: You can simply talk about how words are combined. An even rarer term for a common thing is morphology: putting words and bits of words together to make longer words, like the three pieces of “un-lady-like.”

Linguists love morphology, but when talking to wider audiences they’re better served by talking about building words out of smaller pieces. When you will not be re-using terms frequently, rephrasing is your best strategy.

Acronyms and initialisms are common in technical writing, but they are wearying to a reader who is not familiar with them, and deadening even to one who is. You may think that, having defined “hyperemesis gravidarum” once, you can simply go on to refer to HG throughout your writing. But this forces the reader to recall the unfamiliar phrase behind the initials; it saves you a few keystrokes at the expense of the reader’s ease.

Instead, consider short forms and simple synonyms. Hyperemesis gravidarum can be the condition on later mentions, or something general like nausea where precision is not crucial. A bit of work to vary your vocabulary, rather than monotonously repeating strings of capital letters, will do wonders for keeping your reader’s attention.