Ask Ethan #111: Do Galaxies Die?

Even the cosmic home where our Solar System resides will someday meet it’s demise. But how?

“Unless one says goodbye to what one loves, and unless one travels to completely new territories, one can expect merely a long wearing away of oneself and an eventual extinction.” –Jean Dubuffet

There were so many good questions and suggestions this week for our Ask Ethan column that I had to ask for help deciding. After some intense head-scratching, I decided to go with John Little’s submission, which requires us to go far into the future:

Do galaxies die? If they do, then what would they look like?

We can start by looking close to home, at our own Milky Way and its surroundings.

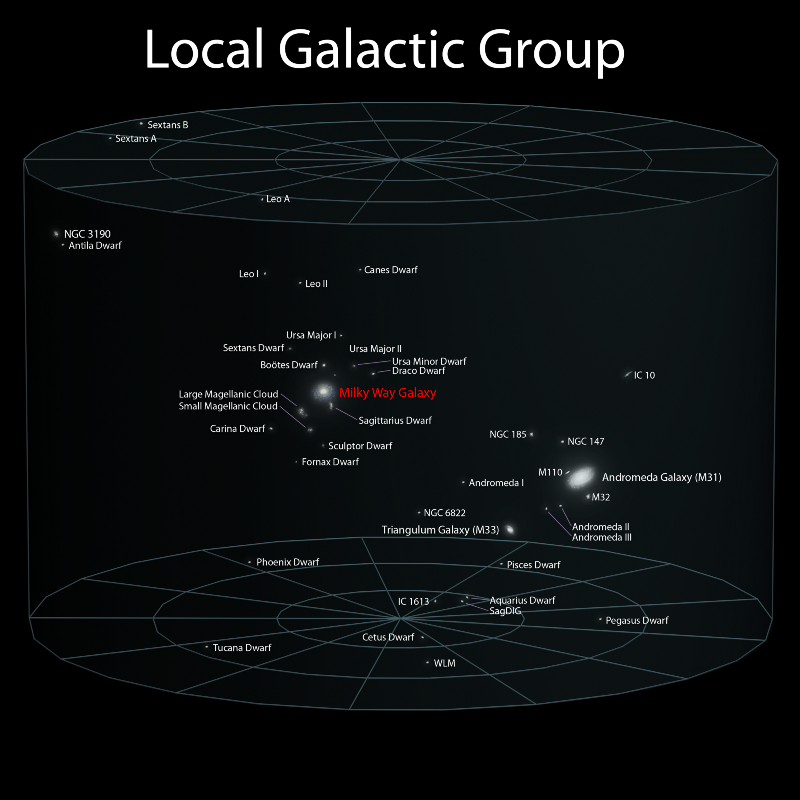

While we tend to think of the local group — our cosmic neighborhood — as being made up of ourselves, Andromeda (our big sister), and a bunch of nobodies, it’s high time we recognize the rest of what’s around us. In particular:

#3: the Triangulum galaxy. At around 5% of the Milky Way’s mass, this is the third largest galaxy in the local group. It has a spiral structure, its own satellites, and may itself be a satellite of the Andromeda galaxy.

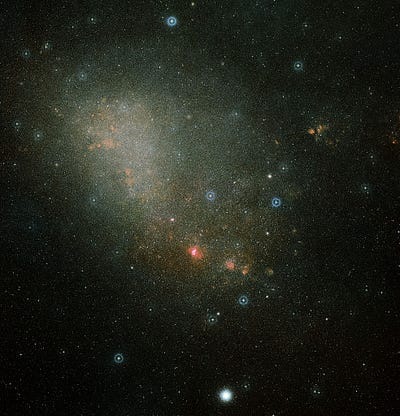

#4: the Large Magellanic Cloud. This galaxy is only 1% of the Milky Way’s mass, but is the fourth largest in the local group. It’s very close to our Milky Way — less than 200,000 light years away — and is undergoing a burst of star formation, as our galaxy’s tidal interactions are causing gas to collapse, giving rise to some of the newest, hottest and largest stars in the Universe.

#5–7: the Small Magellanic Cloud, NGC 3190 and NGC 6822. All between 0.1% and 0.6% of the Milky Way’s mass (it’s uncertain which one is largest), these three are substantial galaxies in their own right as well, with over a billion solar masses’ worth of material in each one.

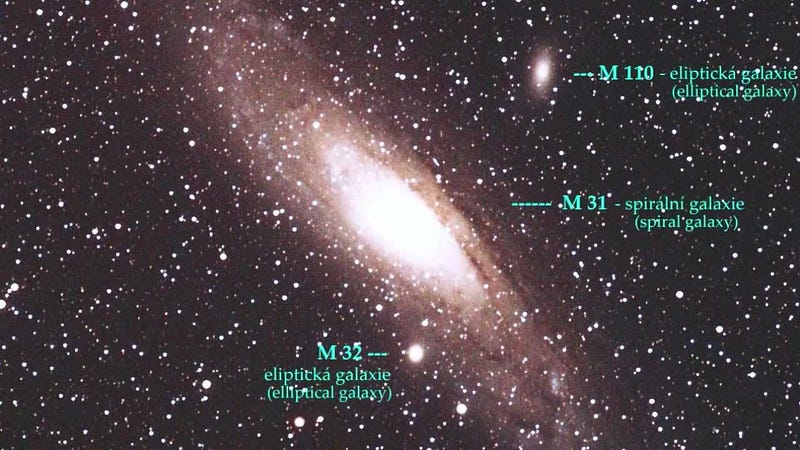

#8 & 9: Elliptical galaxies M32 and M110. These might “only” be satellites of Andromeda, but these ellipticals have over a billion stars inside each, and may yet be more massive than some of the galaxies numbered 5, 6 and 7 above.

And beyond that, there are at least 45 other known galaxies — smaller galaxies — making up our local group.

Despite their sheer numbers, their masses and their magnitudes, not one of them will exist the way they are right now another few billion years into the future.

As time goes on, galaxies gravitationally interact. This not only pulls them together by the gravitational attraction you picture normally, but there are also tidal interactions. We normally think about tides as something the Moon creates by pulling on the Earth’s oceans, causing a bulge in one direction that gives us “high tide” when the Earth rotates through the bulge and “low tide” when we rotate through the trough, which is true enough.

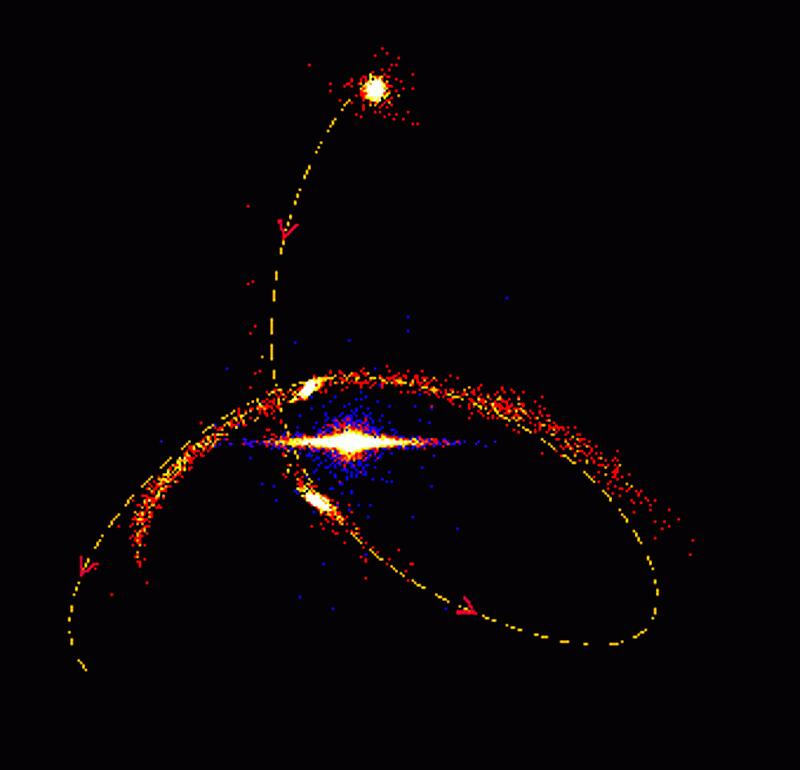

But from a galaxy’s point of view, tides are a little more subtle. The portion of a small galaxy that’s closer to a larger one will be attracted with a greater gravitational force, while the portion that’s farther away will experience a lesser attractive force. As a result, small galaxies get stretched and eventually torn apart by their interactions with larger ones.

The small galaxies that are a part of our local group, including both Magellanic clouds and all the dwarf ellipticals, will be torn apart in exactly this fashion, and their matter will be incorporated into the larger galaxies they merge with.

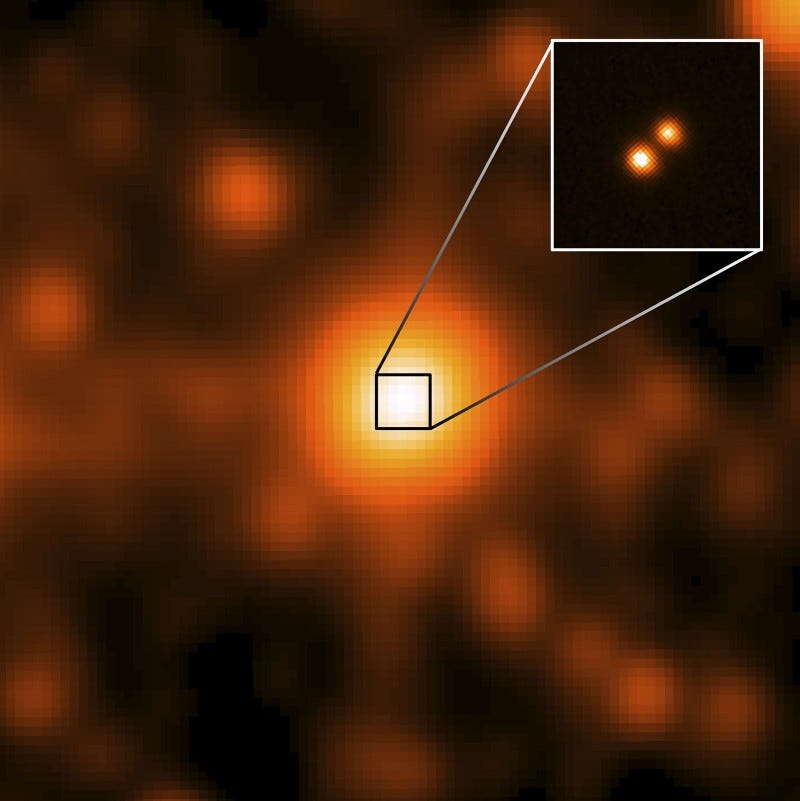

“So what,” you say. That’s not a true death, because the big, Milky Way-like galaxies still survive. But even we won’t live forever in our current state. About 4 billion years in the future, the mutual gravitational attraction of the Milky Way and Andromeda will pull us into a gravitational dance with one another, leading to a major merger. Although the entire process will take billions of years to complete, the spiral structure of both galaxies will be destroyed, resulting in the creation of a single, giant elliptical galaxy at the core of our local group: Milkdromeda.

Eventually, the other galaxies within our local group will be sucked in as well, leaving just a single, giant galaxy made up of the cannibalized remains of all the others. This process will happen, eventually, in all the bound groups and clusters of galaxies throughout the Universe, while dark energy drives all the individual groups and clusters apart from one another.

But again, that’s not a true death, because there’s still a galaxy present. At least, for the time being, that’s the truth. But the galaxy is made up of stars, gas and dust, and there’s a finite amount of all of them.

While the mergers will take tens of billions of years to complete, and dark energy will drive them apart and across the Universe towards invisibility and inaccessibility on timescales of hundreds of billions of years, the stars within will live on. The longest-lived stars in existence today will continue to burn their fuel for more than ten trillion years, and from the gas, dust and stellar corpses littering each galaxy, new stars will be born — albeit in smaller and smaller numbers and less frequently — throughout that time.

Even when the last star burns out, the stellar remnants — white dwarfs and neutron stars — will continue to shine for hundreds of trillions or even quadrillions of years before going dark. When that inevitability happens, we’ll still have brown dwarfs, or failed stars, merging together occasionally, reigniting nuclear fusion and creating starlight for tens of trillions of years at a time.

When that last star burns out, though, tens of quadrillions of years (some ~10^16 of them) in the future, the mass in the galaxy will still be present. Even that cannot be considered a “true death” in some senses.

Even without light, the galaxy itself will not last forever! All of these masses are gravitationally interacting with one another, and gravitational objects of different masses have a strange property when they interact:

- The repeated “passes” and close encounters cause exchanges of velocity and momentum between them.

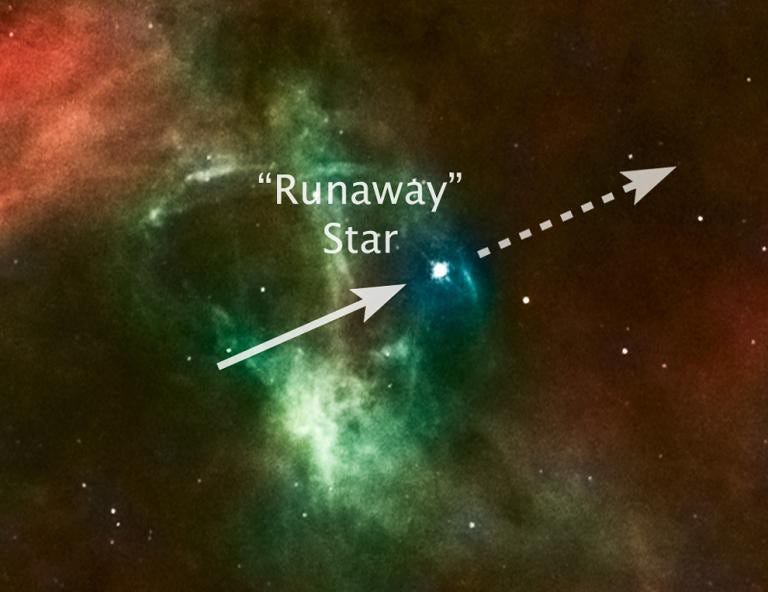

- The lower-mass objects get kicked out of the galaxy, while the higher-mass objects sink towards the center, losing velocity in a process known as violent relaxation.

- Over long enough timescales (~10^19 to 10^20 years), most of the mass of the galaxy will have been ejected, with only a small percentage of the remaining masses more tightly bound.

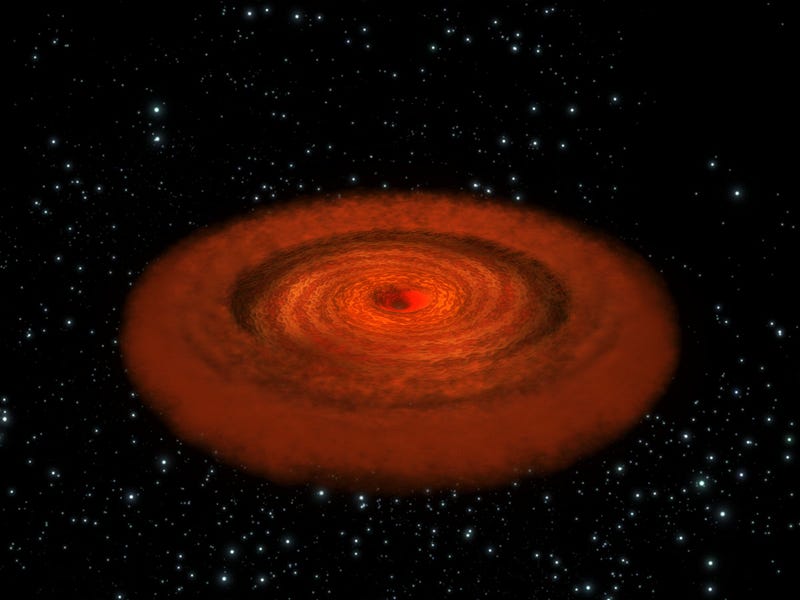

At the very center of this galactic remnant will be the supermassive black hole at the center of each one. This will, of course, be the last and final thing to go: it will get as large as it can from eating as many objects as it can get its hands on. At the center of Milkdromeda, we’ll likely find an object a hundred million times as massive as our Sun is today; larger groups and clusters might have black holes exceeding ten billion solar masses or even higher!

Yet even these won’t live forever.

Thanks to the phenomenon of Hawking radiation, even these objects will decay away. It will take somewhere between 10^80 and 10^100 years, depending on how massive our supermassive black hole gets, but even this, too, will go away.

No matter how you define a galaxy or its remnants, all of them will most certainly die. As to when and how, the exact answer is up to you!

Have a question or suggestion for Ask Ethan? Submit it for our consideration.

Leave your comments at our forum, and if you really loved this post and want to see more, support Starts With A Bang and get some rewards on our Patreon!