Ask Ethan: Do Blue Skate-Suits Really Go Faster Than Red Ones?

The medal-winning Norwegian team had a most unusual explanation for why their speed skaters wore blue. Is there any science to back it up?

Every four years, the Olympics come around, and the greatest athletes from all over the world come together to compete. Although the competition is friendly, there’s a tremendous amount of science and engineering behind how an athlete trains, conditions, and works to maximize their natural gifts. Not to be outdone, the technology supporting these athletes has also changed and improved tremendously, resulting in a kind of athletic arms race to maximize the athletic performance of each country’s members. Recently, a rumor has gone around about speed skating and the color of the skate suits, claiming that blue is the fastest color. Sound crazy? It does to Pamela Holt, who asks:

Ethan, I’ve been watching the Olympics, and I heard that it’s been proven that blue skate suits are faster than red. Is this true?

There’s a lot to consider when it comes to speed skating, but did you ever imagine that color could be one of them? Let’s investigate the claim.

There are only a few factors at play when it comes to evaluating a skating suit for speed skating, but they’re all important factors. After all, this is a sport where every millisecond counts! These include:

- the comfort of the suit when the wearer is in their racing position, to reduce unnecessary effort,

- the lightness of the material, to cut down on unnecessary weight,

- the level of compression on a variety of muscles, to maximize the ease-of-motion and application of force to the ice,

- the ability to create the minimum amount of drag, allowing the skater to attain and maintain the highest top speed,

- and the reduction of friction to a minimum, meaning less expended energy is lost while skating.

In short, you want to empower the skater to go as fast as possible as easily as possible, and to reduce or eliminate any factors that might hinder that.

In 2014, there was a big hullabaloo about Team USA’s new Under Armour skate suits, which had a bizarre look to them never-before-seen. Most glaringly, the suits were outfitted with a grey, mesh crotch area known as “ArmourGlide.” The alleged rationale for the redesign was to reduce friction between the skaters’ thighs, which were thought to be responsible for slowing them down. This was a debacle, however; despite testing over 100 different textiles and spending over 300 hours in a wind tunnel, not only did Team USA fail to medal in speed skating at the Sochi Olympics, but many blamed the suit as being sub-optimal for air resistance. While venting is important for the human body — fabrics need to “breathe” — athletes claimed, contrary to reports from USA Speed Skating and Under Armour, that the vents allowed too much air to enter the suit, slowing their speed as a result.

There’s a reason that speed skaters take the classic pose you see them in: bent over in a crouch, their upper body flat like a table, arms tucked. It’s to minimize air resistance. Air resistance is a drag force that slows you down, and the way it slows you down is nefarious. Yes, the faster you go, the greater the drag force, but if you go twice as fast, the drag force is four times as great. Riding in a convertible at 30 MPH might be fun for almost everyone, but at 60 MPH it’s very uncomfortable for many. At 120 MPH, it’s something practically no one would choose, approaching what a skydiver would experience in terms of air resistance. For a speed skater, that 30 MPH speed needs to create as little drag as possible if they have any hopes of winning. Positioning is a huge part of that. The rest, however, is technology.

Many advances have gone into speed skating suits over the years. For short-track racers, they spend approximately 80% of their time turning left, meaning that suits are best designed with comfort, compression, and low wind resistance optimized for that position. Suit design is not only a point of national pride, but a burgeoning multimillion dollar industry, with countries designing their own, optimized suits for their skaters. Which is why it was such a surprise when Norway, a traditional speed-skating powerhouse with (prior to 2018) 80 Olympic medals in the sport (2nd all-time), abandoned their traditional red suits for blue ones for these Olympic games.

Why? According to Håvard Myklebust, a researcher and sport scientist for Norway, “We had not chosen blue if it had not given us a favorable difference. It fits the speed profile for the air resistance of the fabric.” The Norwegians, Germans, and South Koreans are all wearing the same blue colored suits at these Olympics, believing it gives them a competitive advantage. According to Dutch long-track sprint specialist, Dai Dai Ntab, “It’s been proven that blue is faster than other colors. Every Olympic season, everybody is trying to find the hidden gem. This year it’s the blue suits.” The Netherlands, all-time leaders in Olympic medals in speed skating, are sticking to their traditional orange color.

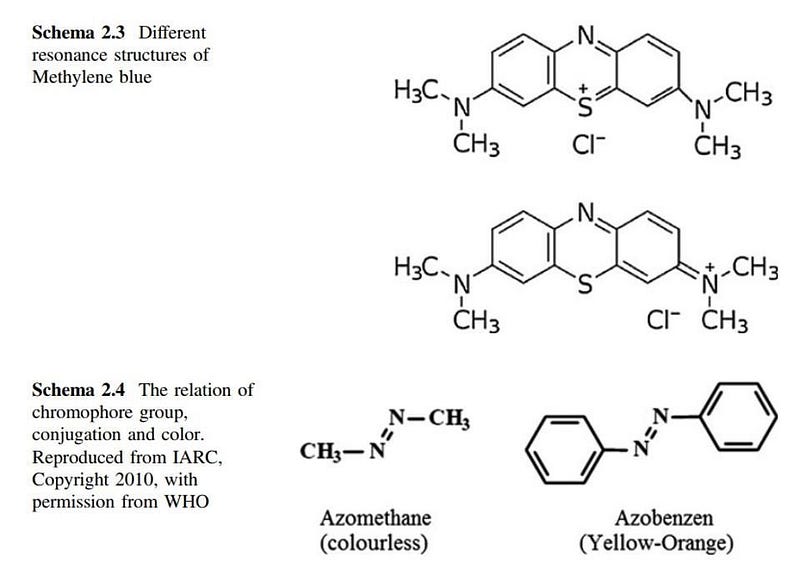

But these radical claims seem to defy logic. Dyes and pigments are based on molecules added to a fabric, where the molecules themselves are only nanometers in size. The differences between red and blue are minuscule, where the only thing that determines the color is the energy of the photons absorbed by the molecules. This typically has very little to do with a molecule’s size or mass, nor its ability to deform to the fabric it adheres to. From a scientific perspective, there’s no reason to believe that the color of a dye or pigment would have anything to do with a suit’s performance.

Beyond that, though, you can always look to the experimental results. After all, it’s always possible that our best theories or ideas are inadequate to explain what’s actually going on. Conventional wisdom will get overturned when a new effect, previously thought unimportant, comes into play. Could the blue dyes or pigments cause the Norwegian or German teams to topple the Netherlands? Will the blue suits, perhaps in the way they bond to the fabric, give them a competitive advantage?

As of Saturday morning, February 17th, Norway is in fact leading the medal count with 19. But only one medal — a bronze for Sverre Lunde Pedersen in the men’s 5000 meters — came in either short track or speed skating. Germany, with 15 medals, has thus far failed to medal in speed skating at all. And the Netherlands? All 13 of their medals have come in either short track (2) or speed skating (11), including six golds. If blue really is the fastest color, the evidence doesn’t support such an assertion. Either that, or the alleged Dutch training program, where they tongue-in-cheek claimthat their frozen canals lead them to train even as they speed-skate to work, gives them an advantage so great that even with a color disadvantage, they can still win.

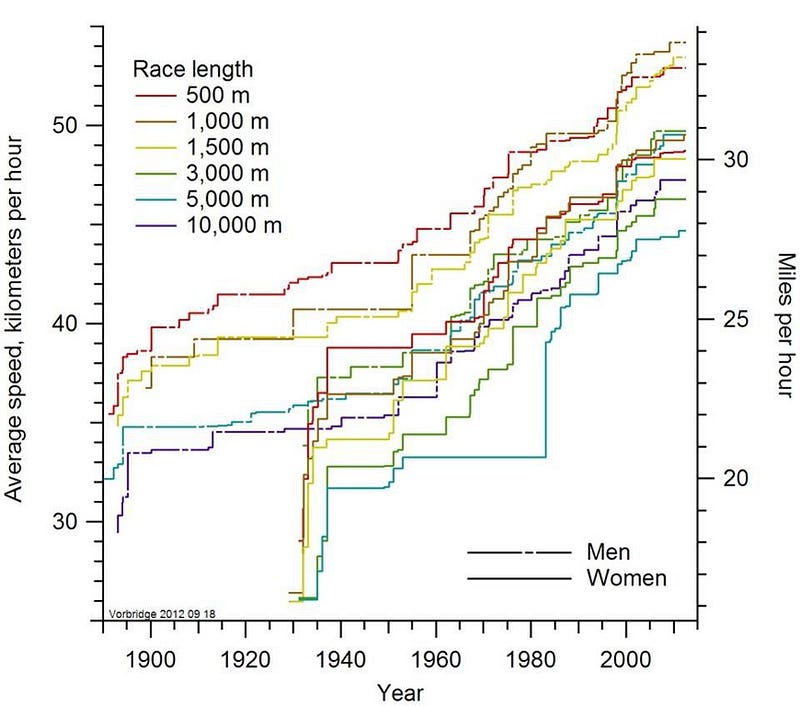

The advances in suit design do, in fact, play a major role in not only Olympic success, but in speed skating in general. Along with training and technique, advances in aerodynamics, materials and textiles, and the reduction of both drag and weight have shaved significant seconds off of skaters’ times. Over the past 30 years alone, for example, the typical average speed for a top skater has increased by around 15%. In the Men’s 5000 meter race, for example, Ted-Jan Bloemen’s current record of 6 minutes, 1.86 seconds is 42 seconds faster than Geir Karlstad’s record from Calgary in December of 1987. World records in the other events have progressed similarly, largely due to those same improvements in technique and equipment.

So is there any evidence that blue suits do go faster than red, or any other color, for that matter? Not at all. The results don’t bear that out, and scientific theory doesn’t support that it should, either. The only truth that could be behind it is that some dye/pigment molecules don’t adhere well to certain fabrics, and it’s possible that the traditional red dyes that Norway has used for so long don’t play well with the textiles that make up the 2018 suits. There’s no doubt that the new suits are faster than the old ones, but it’s dubious at best that color has anything to do with that. Olympians are famous for their non-scientific superstitions, but this color-switch may have the most mundane explanation of all: Lerøy Seafood Group sponsored the suits, and the suit color matches their company color perfectly. Until the science says otherwise, that’s the explanation I’d bet on for the new, blue suits.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.