Can Science Ever Be “Settled”?

You’ll frequently hear people say “the science is settled.” Scientifically speaking, can it ever be?

“All the problems of the world could be settled easily if men were only willing to think. The trouble is that men very often resort to all sorts of devices in order not to think, because thinking is such hard work.”

–Thomas J. Watson

Gravitation. Evolution. The Big Bang. Germ Theory. Global Warming.

They’re all scientific theories, and they’re all referred to as examples of “settled science” in various circles. Yet, is that even possible? After all, one of the most important cornerstones of science is the willingness to challenge the conventional wisdom. Science advances not merely by accepting the current best explanations as a foregone conclusion, but by testing them, probing them, pushing their limits and looking for gaps. After all, what was once accepted as the consensus position is laughably inadequate in light of our present knowledge and understanding.

But hold on. Just because something is open to revision if-and-when new information comes in doesn’t mean there aren’t aspects that have been so rigorously tested — that are so scientifically robust — that they can be considered “settled” or “correct enough” no matter what else we learn.

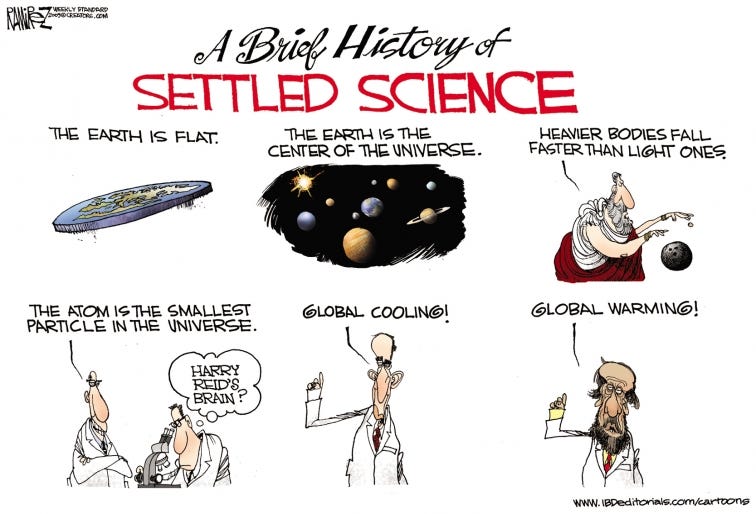

Many of the examples in the image above, in fact, aren’t good examples of “settled science” by that metric: the idea of a flat Earth was never a scientific theory, neither was the descriptive geocentric model (as science is also prescriptive), and the idea that global cooling was imminent was — despite widespread exposure — never a consensus position. But just because science is continuously challenging itself, assimilating new information, and revising its conclusions, doesn’t mean there aren’t many aspects that can be considered settled, at least at present. Let’s take a further dive inside.

1.) Gravitation. It is true that Aristotle’s idea — that heavier objects fall faster than lighter ones — is not the best, most universal description of gravitation. But had Galileo gone up to the top of the Leaning Tower of Pisa and actually performed his famous experiment, dropping two balls of different mass off the top, the heavier one really would have hit the ground first! This isn’t, of course, because heavier objects experience a different gravitational pull than lighter ones, but rather because the deceleration due to atmospheric drag depends on an object’s surface-area-to-mass ratio, and heavier objects have smaller ratios than lighter ones.

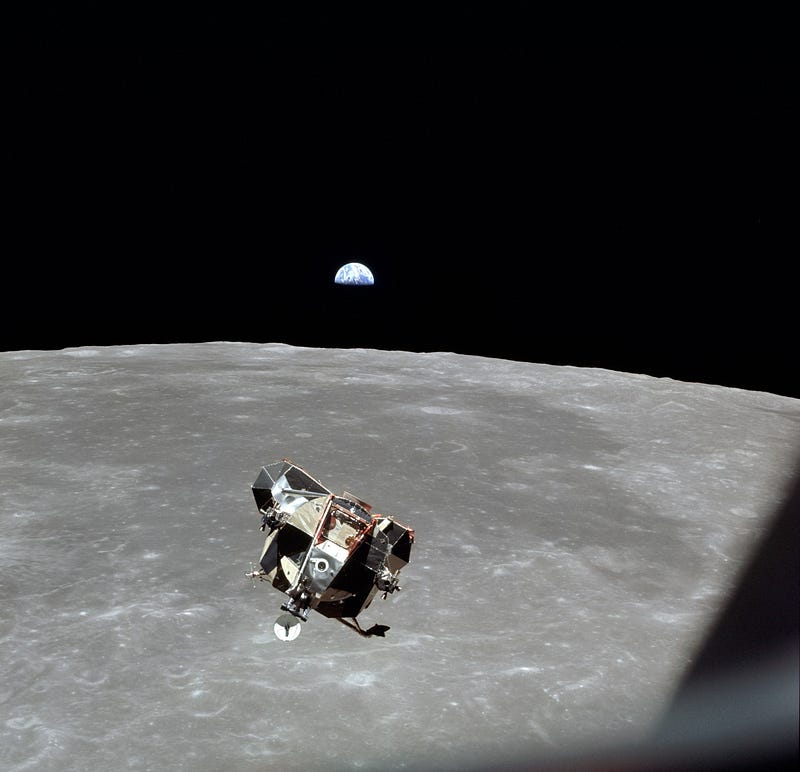

But it’s fair to say that we didn’t have a satisfactory model of gravitation until Newton came along, and explained how objects in the Universe exerted gravitational forces on one another. From objects on Earth to the planets and stars in the Universe, Newton’s theory was both predictive and also retrodictive. This means it quantitatively explained gravitational phenomena that had occurred in the past and also allowed us to successfully predict gravitational phenomena that would occur in the future. It was, in fact, Newton’s equations that allowed us to successfully navigate our way to the Moon.

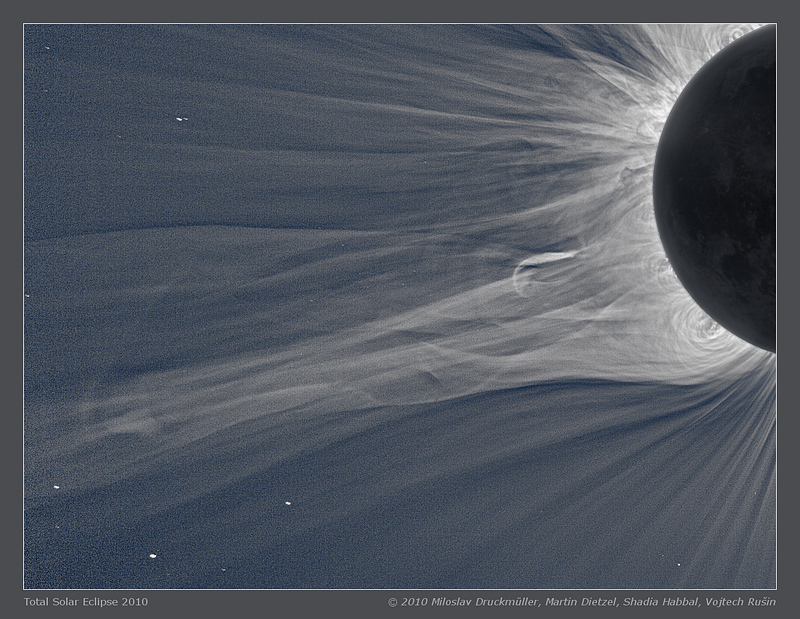

And yet, Newton’s gravity isn’t our best theory of gravitation. It has its limitations, and it has realms where it no longer accurately predicts gravitational phenomena. In particular, in strong gravitational fields and at velocities approaching the speed of light, Newtonian gravity must be replaced by Einstein’s general relativity, which relies on the curvature of space. It was, in fact, during a total solar eclipse that Einstein’s theory was verified, as the positions of the stars visible during that time matches the prediction of Einstein’s theory and not Newton’s.

Yet even Einstein’s theory will surely be replaced by a better one at some point in the future. General relativity gives nonsense answers for what exists at the center of a black hole, and has nothing to say about the Universe on scales below a certain distance threshold.

Does that mean that it’s wrong to consider gravitation a “settled” science?

Of course not! Even Newton’s gravity can be considered settled science, in the sense that in its realm of validity, it always predicts the correct answer to a certain degree of precision. Scientific revolutions do occur, but so long as the science has been robustly tested and verified up until that point, what came before isn’t wrong so much as it is incomplete. So science can be both settled — in the sense that explanations for many things can be well understood — and also open to refinement and growth.

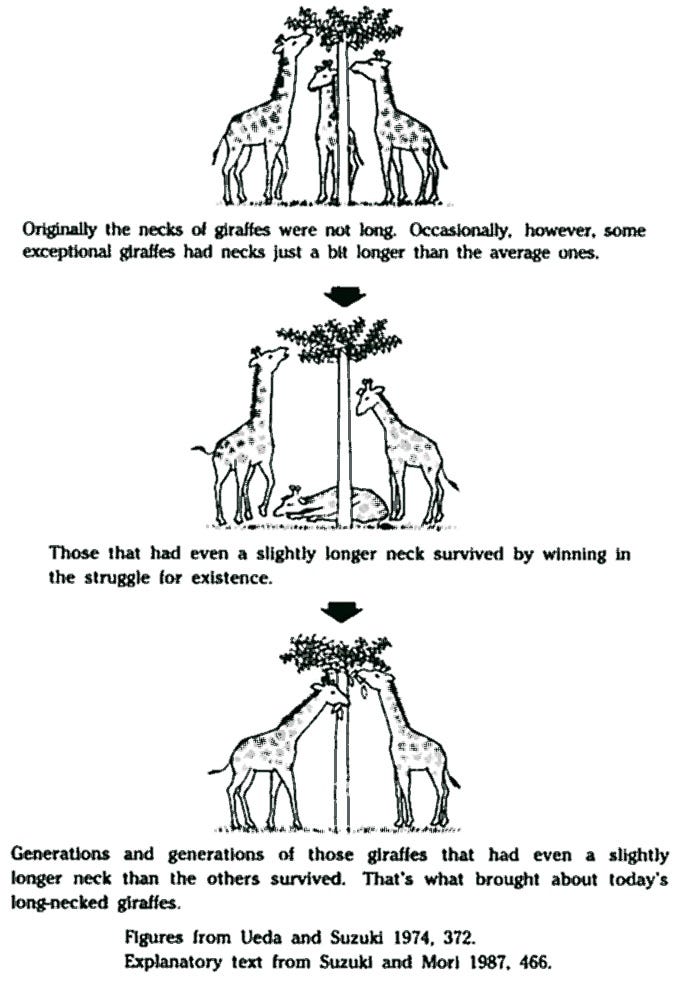

2.) Evolution. So it goes for evolution as well. It’s been known for millennia that the physical characteristics of organisms change and vary from one generation to the next, and that over long periods of time, the traits of an entire population can change as well. Yet the mechanism of how evolution works was poorly understood until Darwin came along, and he identified two complementary aspects: mutations, where subsequent generations could inherit traits that none of their ancestors possessed, and natural selection, where the organisms least fit for survival died out. Over time, these two things — in combination — resulted in the phenomenon of evolution that had been observed for so long.

This, too, is settled, in the sense that it has been robustly demonstrated to be a correct description of how virtually all life on Earth has evolved to its present state from a common ancestor. Although this, too, is not the complete story. Evolutionarily, gradualism and punctuated equilibrium tell a more nuanced story of evolution that Darwinism — in its original form — alone. Mendelian genetics further improved upon Darwin by explaining how information was passed from one generation to the next, and the discovery of DNA and RNA provided an even deeper understanding for the molecular code behind those genetics. No doubt, current and future developments will increase our nuanced understanding even further, but in no sense should we expect that Darwinian evolution will remain anything but settled in its realm of validity as time goes on.

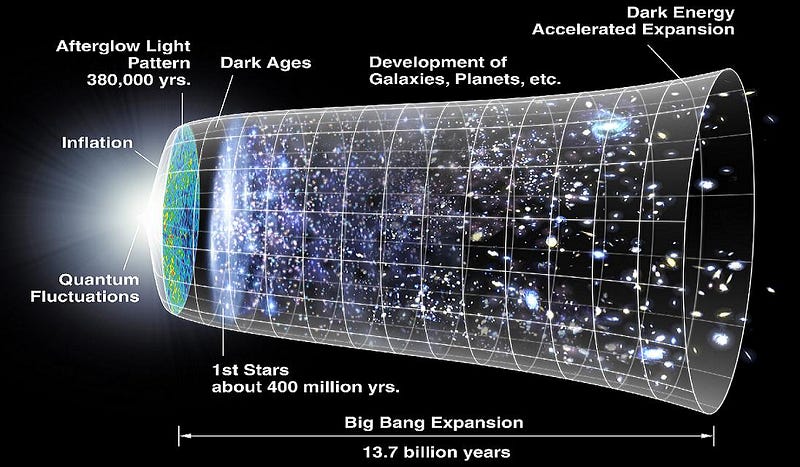

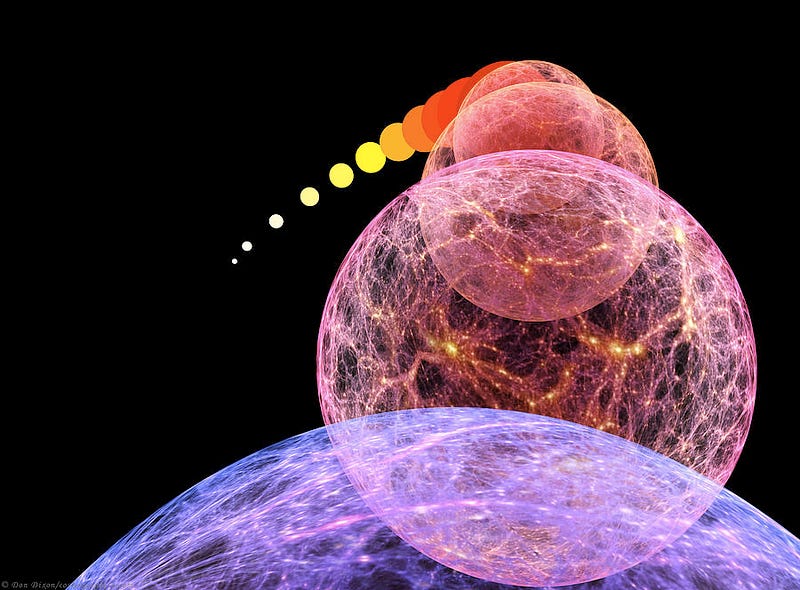

3.) The Big Bang. You begin to see where I’m going with these. There’s a portion of this that should be considered “settled” due to the suite of evidence we’ve collected and the overwhelming power of the theory to accurately predict and retrodict phenomena in this Universe. The Universe — in the distant past — was in a hot, dense state full of matter and radiation, and it expanded and cooled, forming atomic nuclei, neutral atoms, and eventually stars, galaxies and clusters. After many generations of stars lived-and-died, heavy elements and complex molecules became common, as did stars with rocky planets and the ingredients for life.

But this, too, has been (and will likely continue to be) improved upon. In addition to this story, we think the Universe is filled with dark matter and dark energy, and that a period of cosmic inflation preceded and set up what we think of as the hot Big Bang. None of this invalidates the Big Bang or unsettles it, but it serves as a reminder that even our best, most successful scientific theories are limited in their scope and range of applicability.

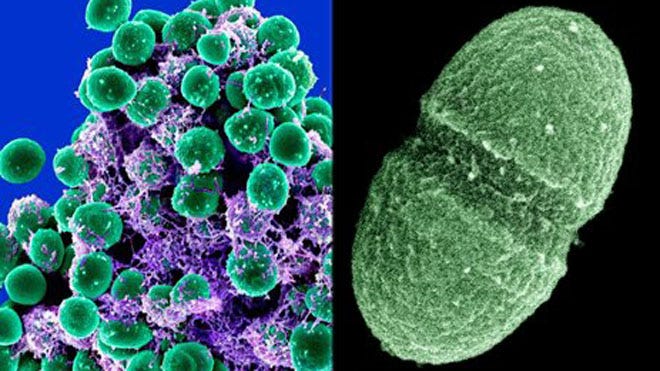

4.) Germ Theory. The idea that some diseases are caused by microscopic organisms was an extremely unsettling one when it was first proposed, yet it’s also been one of the most useful medical discoveries in all of human history. By no means is germ theory a complete description of illness or of the microscopic world, but given the effectiveness of modern medicine in combatting and preventing a whole host of diseases, it’s difficult to imagine that germ theory would ever be invalidated.

And yet there is still so much more for science to learn! The huge diversity of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, protists and viruses, some of which are parasitic and some of which are symbiotic (and some of which are a little of both) belie an incredibly complex and nuanced world. Diseases can be caused by a number of other factors that have very little to do with microorganisms, such as some autoimmune disorders, lethal genetic mutations, chemicals or other poisons. These theories are not complete (no scientific theory really is), but there are certainly aspects of them that can be considered as settled.

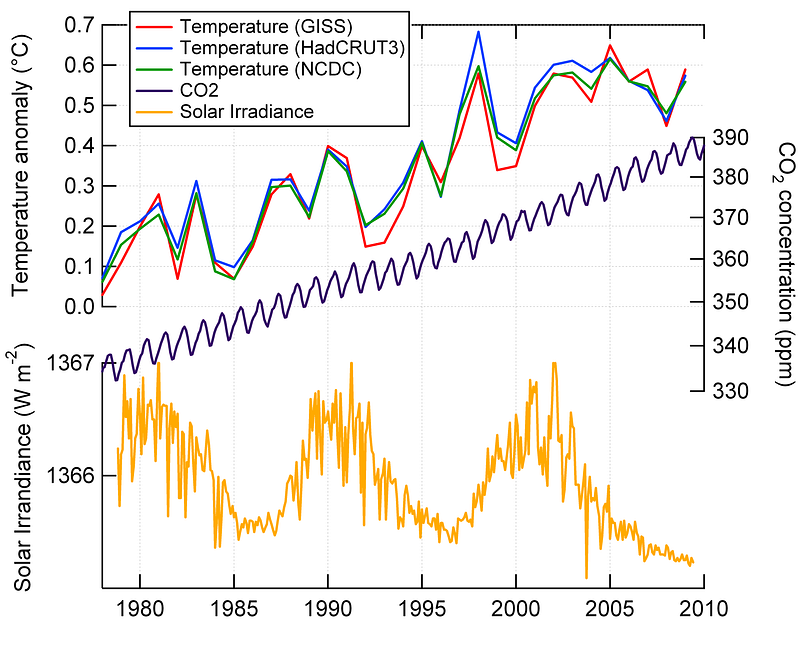

5.) Global warming. And this is perhaps the most politically contentious scientific issue in the modern world. You probably already have your mind made up as respects what you think about this issue before you even read these words. Indeed, the idea that the science could ever be settled on this issue really riles some people up, and people are quick to label those with different opinions from their own as “alarmists” or “deniers” as the case may be.

Yet there are some scientific facts surrounding the climate that are settled: one is that the Earth has been warming and continues to warm significantly, and the second is that the concentration of heat-trapping gases in the Earth atmosphere has also increased by a significant percentage over the past two centuries due to human activity. Scientifically, the chances that the observed warming is a fluke, chance event is only 0.002%, meaning that we are 99.998% certain that the Earth is legitimately warmer today than it was a century ago. It would be unfair to science — both the scientific process and the scientific body of knowledge — to not consider these two pieces of the puzzle “settled.”

But there are other things that are open questions. The Earth’s climate stays within a (quasi-)stable range, where the climate remains relatively stable over time. Natural causes and variations have been seen (in the historical records) to shift that stable point over time; we believe that human causes can do that at well. But where is that “tipping point,” where we’ll transition to a new stable point that’s different from the old one? And what will that stable point look like, and what are the consequences that will ensue? On these points, science continues to make progress, but it is not yet settled. There is simply too much we do not yet understand.

But this is the power and the potential of science, and this is what we all ought to love about it.

The idea that the foundations of science can be shaken so easily by a surprising, reproducible observation or experiment is an important one, but it’s an important one only insofar as it helps separate science from non-science. (Or, if you prefer, pre-science.) At this stage in our understanding of the Universe, scientific revolutions must encompass the success of the previous theories that came before it, which is why general relativity includes Newtonian gravity, and which is why any viable candidate for a quantum theory of gravity must include general relativity (and all of its successful predictions) as a necessity.

When we say the science is settled, we don’t mean that we’ve stopped learning. In fact, we mean the exact opposite: that we have actually learned something valuable. “Settled science” isn’t the end of knowledge, it’s a mark that we’ve begun to legitimately understand something. But remember that the unsettling of settled science is always possible, and we must always keep our mind open to that possibility. If Earth’s gravity stopped working tomorrow and we all floated off into space, if animals began being born genetically identical to their parents, if the Universe began contracting, if germs were eradicated but the diseases they caused persisted, or if the next few years on Earth were a few degrees cooler globally, any one of these “settled” scientific facts would immediately cease to be so. Being “settled” doesn’t mean we’re 100% certain it’s correct, but it does mean that this is the best conclusion we can draw given what we know so far. And as what we know changes and grows, so does the breadth and depth of what “settled science” actually includes.

Have something to say? Why not check out the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs and weigh in with your opinion?