Messier Monday: A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy, M23

Amidst the great plane of the Milky Way, a glittering masterpiece awaits.

“[T]his all fades to black, and it’s gone. It’s dust. Choose carefully what you obsess about.” -Meshell Ndegeocello

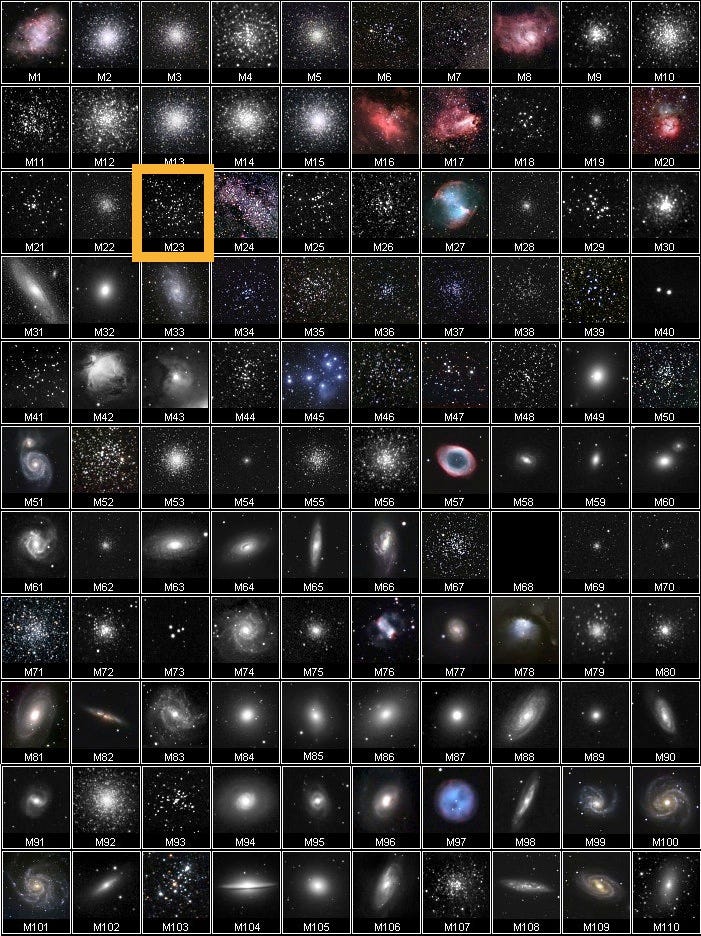

But like everything in the Universe, before the brightest stars fade away, they have their chance to shine. And nowhere will you find large numbers of intrinsically bright stars in our galaxy than in the open clusters, the collections of young nurseries where infant stars live for the first few hundred million years of their lives. While the most common Messier objects are the distant galaxies (with 40) followed by globular clusters (with 29), there are a respectable 26 open clusters, the vast majority of which can be found in the galactic plane.

Today’s object is one of the first open clusters discovered by Messier and is quite typical: Messier 23 lies right in our galactic plane, oriented relatively close to the galactic center. But unlike the galactic center, this object is only 2,150 light-years away, and hence it stands out with its stars looking brighter and bigger against the backdrop of the Milky Way. Even if the (nearly full) Moon rises while you’re searching for it, it’s still an object worth viewing in the skies tonight!

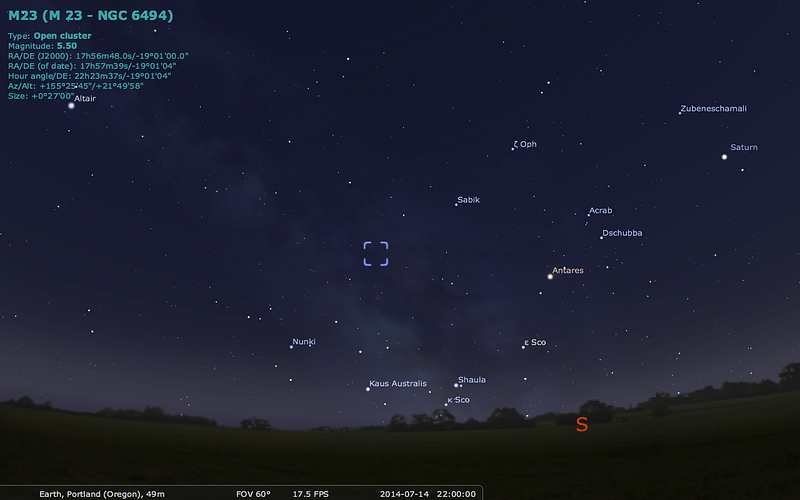

Here’s how to find it.

After sunset and the onset of darkness, a number of bright points of light rise in the southern portion of the sky. Bright Saturn flies high a little towards the southwest, the brilliant orange giant Antares will be very close to due south, and towards the southeast the constellation of Sagittarius begins to rise. If you’re at a dark sky site and the Moon has not yet risen, you may be able to make out the Milky Way, extending from Sagittarius up through the Summer Triangle (and past Altair, at the upper left, above), the birthing ground of these open clusters.

But it’s north of Sagittarius and east of Antares that you should look if you’re questing for Messier 23.

This region of sky — east and south of Sabik but north of Kaus Borealis — actually houses a tremendous treasury of Messier objects: a full 11 are clearly visible in there to dedicated observers!

It’s a little too early in the year to view the more southerly ones easily unless you’re putting in some very late nights, but Messier 23 is still within your reach. The only downside is that there aren’t many bright stars nearby to help guide you! The closest bright star — just below center in the image above — is μ Sagittarii, and if you can identify it, it can lead you to your destination.

About 4.3° northwast of μ Sagittarii, there’s one (unrelated) naked-eye star that’s located on the outskirts of Messier 23: HIP 87782. If you can find that, you won’t be able to miss the collection of bright, blue (and a couple of red) stars shining nearby.

Discovered in June of 1764 by Messier himself, it was first described as:

A star cluster, between the end of the bow of Sagittarius & the right foot of Ophiuchus, very near to 65 Ophiuchi, according to Flamsteed. The stars of this cluster are very close to one another.

But it isn’t that the cluster stars are very close together, it’s that they really stand out from the background stars from the plane of the galaxy!

The Milky Way appears bright and diffuse because of the billions of stars that make it up, but are mostly intrinsically fainter than even our own modest Sun and, on average, many thousands of light-years away. In addition, there are dark dust lanes where small grains of interstellar material absorbs and blocks the light from the stars behind them.

But this cluster — like most open clusters visible from Earth — was formed relatively recently and nearby, and consists of a population of young, dense, close but also intrinsically bright stars!

When star clusters form, they typically come about because a molecular cloud — a cloud of neutral gas coming in at many thousands to a few million times the mass of our Sun — collapses under the immense force of gravitation. They’re more likely to form in the plane of our galaxy than anywhere else, and to form when the density waves of our galactic spiral arms pass over them. When the clouds do collapse, regions of star formation give birth to hundreds if not thousands of stars, ranging from the very dim, low-mass red dwarfs all the way up to ultramassive blue giants!

Over time, the most massive, giant stars die the earliest, as they finish burning through their fuel the most quickly. This cluster consists of some 150 stars that are definitely a part of Messier 23, and contain no O-class stars and only the dimmest and faintest of the B-class stars (B9), placing this cluster at around an age of 220-300 million years. This actually makes it one of the older open star clusters in our galaxy, as gravitation causes these clusters to dissociate on timescales of a few hundred million years (on average).

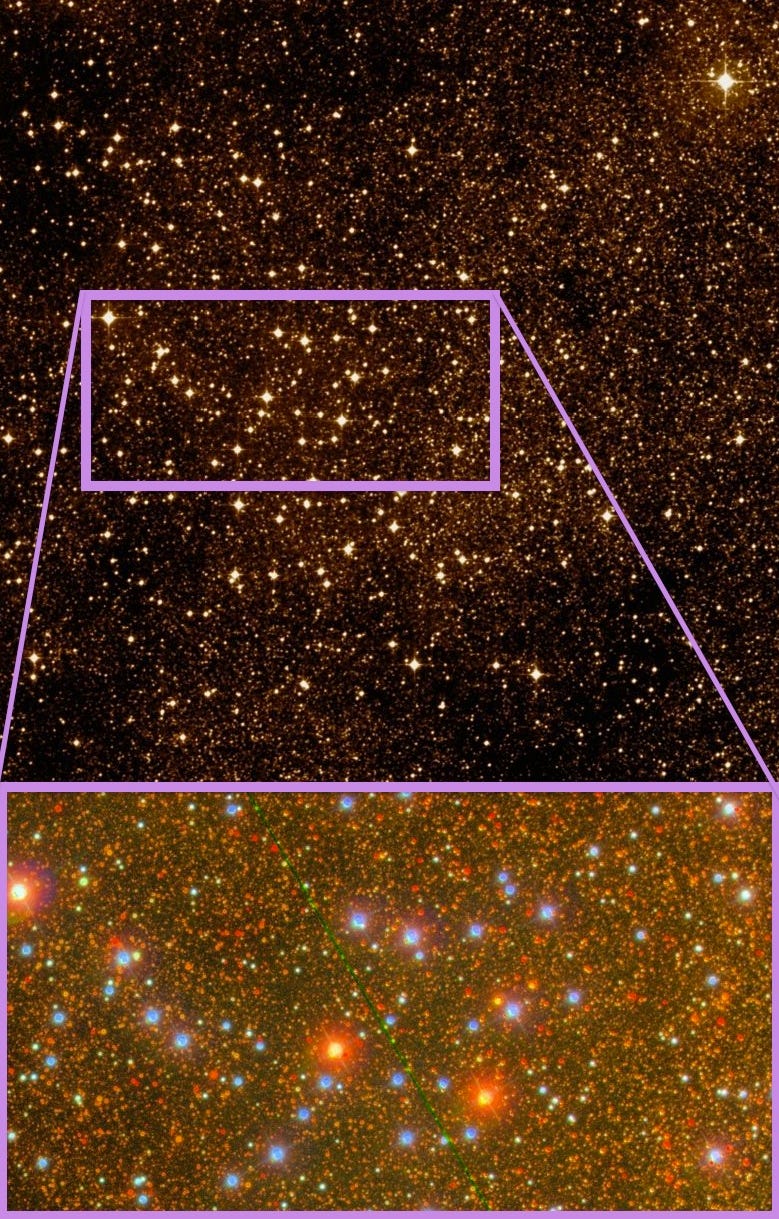

But how many more stars are there inside? To attempt to answer this, let’s take a look at two images: one from the Digitized Sky Survey and one from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

First off, the red stars in here — the brightest ones — are red giants, or stars that have reached the end of their hydrogen-burning phase and are now burning helium in their core. They’ve expanded, and are brighter but cooler than the other stars in the cluster. The blue ones are the B-class and A-class stars that are so prominent, and those are still main-sequence stars, which means they’re still burning hydrogen. But what of all the others? What of the white ones, the yellow and the orange and faint red ones? Which of those are part of this cluster, and which ones are part of the galactic background?

Sadly, we don’t know! That would require doing spectroscopy on each of the individual stars, and those are observations that have never been made. Which is too bad, because doing that would tell us whether there are merely hundreds of stars in here, or whether there are many thousands, which is — if I were a gambling man — what I’d bet on!

After all, with over 100 intrinsically bright stars, there ought to be many dozens of faint ones for each of the ones we can see! This is how populations of stars work and how practically all clusters form; all it would take is one dedicated set of observations with say, Hubble (which has never imaged this object) and then we’d know. Until then, all we have are the observations at our disposal combined with the knowledge of how these things work. It’s speculation to say there are thousands of stars in this cluster, but there’s good reason for that speculation, too!

And that takes us to the end of today’s Messier Monday. Including today’s object, here are the ones we’ve profiled so far:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

With the Moon finally out of the skies next week, we’ll take an in-depth look at one of the great galactic giants of the night. Enjoy the sights of the sky, and I’ll see you back here soon for another Messier Monday!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs.