Messier Monday: An All-Season Cluster, M35

With an unforgettable “blue fog” caused by the galaxy itself that makes it stand out among all the others.

“Derive happiness in oneself from a good day’s work, from illuminating the fog that surrounds us.” –Henri Matisse

We might not realize it — I’m pretty sure that Messier never did — but we do live in a great cosmic fog. Not because there’s something nebulous inherent to space that prevents us from seeing what’s truly there, but because we live in the plane of our galaxy, which itself is filled with not only stars and nebulae, but light-blocking gas and dust as well. Yet if we look in just the right places on the sky, we can find not only stars, but windows into some of the more exotic deep-sky objects in the Universe!

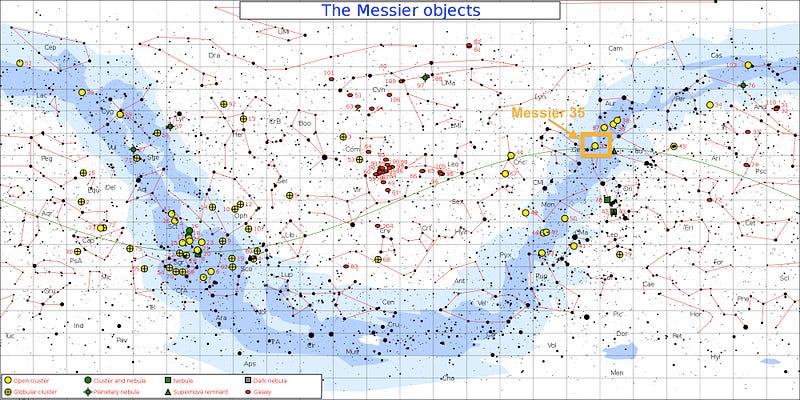

110 of those objects are represented in the Messier Catalogue, the first large, accurate compilation of what we now know are stellar remnants, star clusters and galaxies. While the galaxies are clustered irrespective of our own location, one of the types of star clusters — the open clusters — are almost exclusively found in the plane of our Milky Way. One of them happens to be today’s object: Messier 35, a remarkable star cluster (and a spectacular site) visible practically year-round.

Here’s how to find it tonight.

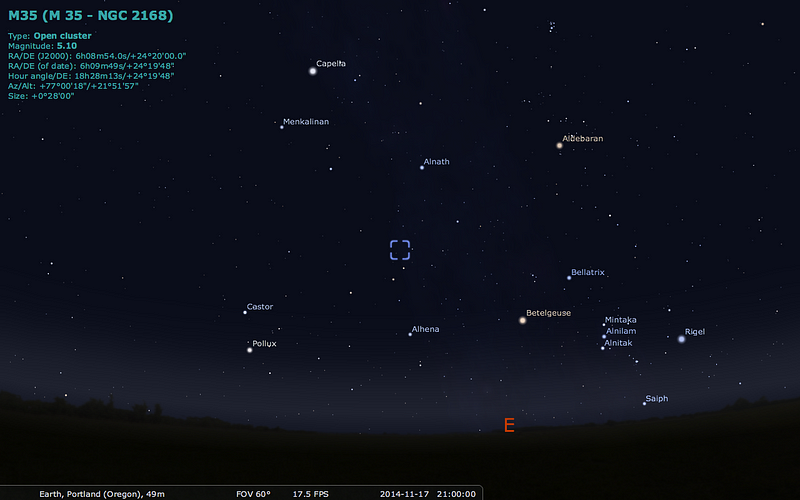

A few hours after sunset, the famed winter constellation of Orion will rise in the east, with bright, orange Betelgeuse pointing towards the north. Other prominent stars are nearby, including brilliant Aldebaran, the incredibly bright Capella, and the “twins” Castor and Pollux, all among the 25 brightest stars in the entire sky.

If you drew a ring connecting these five stars, Messier 35 would lie somewhere very close to the middle, but that’s not a very helpful aide to find it. Instead, connect Betelgeuse to Pollux and find the blue star midway between them: Alhena (still the 41st brightest in the sky), and then “hop” in the direction of Capella.

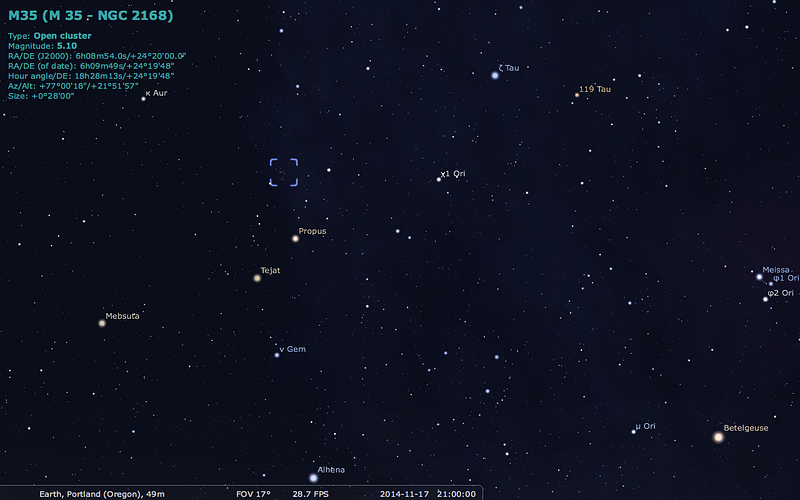

There will be three stars you encounter as you star-hop that require absolutely no visual aides — like a telescope or binoculars — at all: ν Geminorum, Tejat (μ Geminorum), and then Propus (η Geminorum), which is somewhat out-of-line with the others.

If you navigate the same distance-and-direction that you jumped from ν Geminorum to Tejat, and applied that from your jump to Propus to where there are no very bright stars, you would wind up practically atop Messier 35!

The closest thing to a “guide star” is 5 Geminorum, but even that is at the limit of unaided vision. But if you can find it, then right next door is a visually large cluster of stars: about the size of the full Moon. And its appearance is unmistakeable, even for first time stargazers.

Although Messier catalogued this object in 1764, it was independently discovered at least twice before him: by Philippe Loys de Chéseaux in 1745 and by John Bevis, who published it in his early catalogue in 1750. Messier himself found it and described it so:

Cluster of very small stars, near the left foot of Castor, at a little distance from the stars Mu & Eta of that constellation.

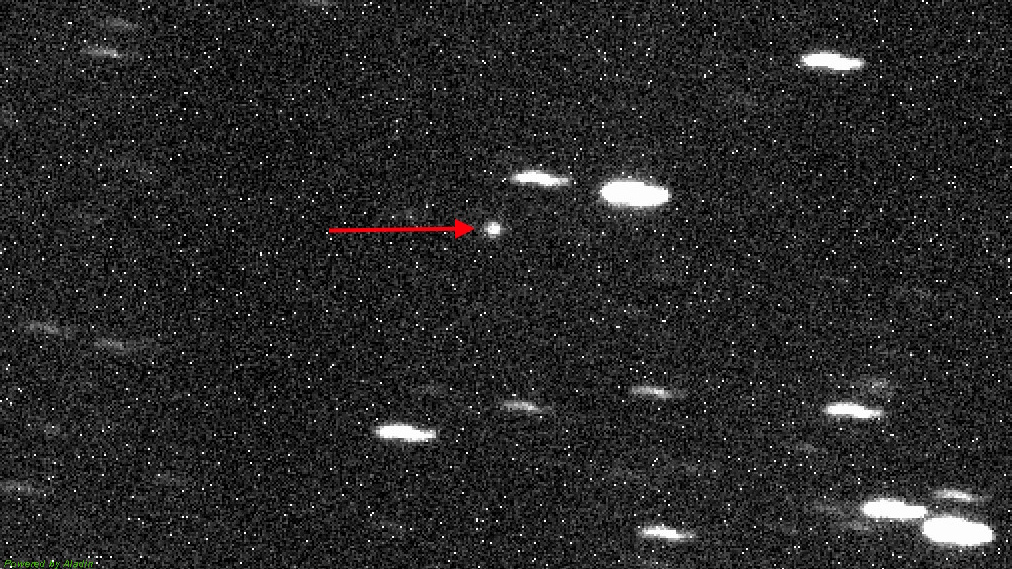

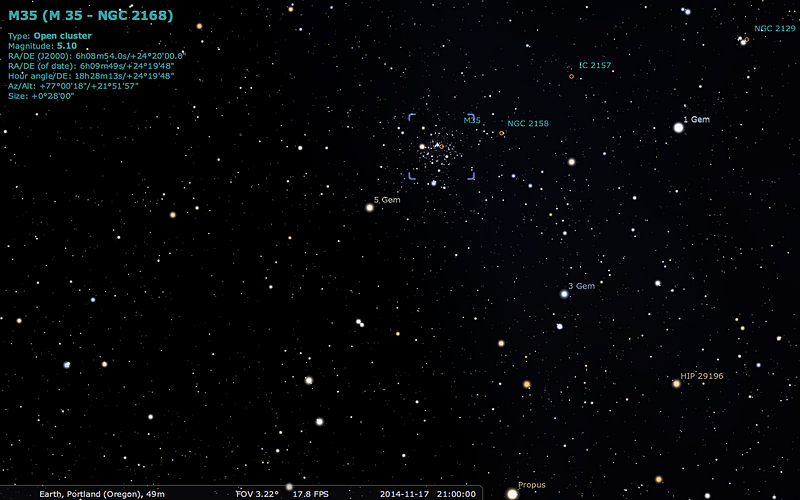

What’s striking at first, particularly through a better telescope, is that this star cluster is not alone!

What looks like a “little sister” is actually a far more distant and much older star cluster that’s also in the plane of our galaxy. You see, it takes huge amounts and dense concentrations of gas and dust — molecular clouds — with around a million solar masses or so to collapse and trigger the formation of new stars. With very few exceptions, these molecular clouds exist only in the planes of galaxies, and the open star clusters we find typically dissipate gravitationally after a few hundred million years, with a few surviving into the billions.

But the easiest ones to find are the closest and youngest, since their stars appear the brightest to us!

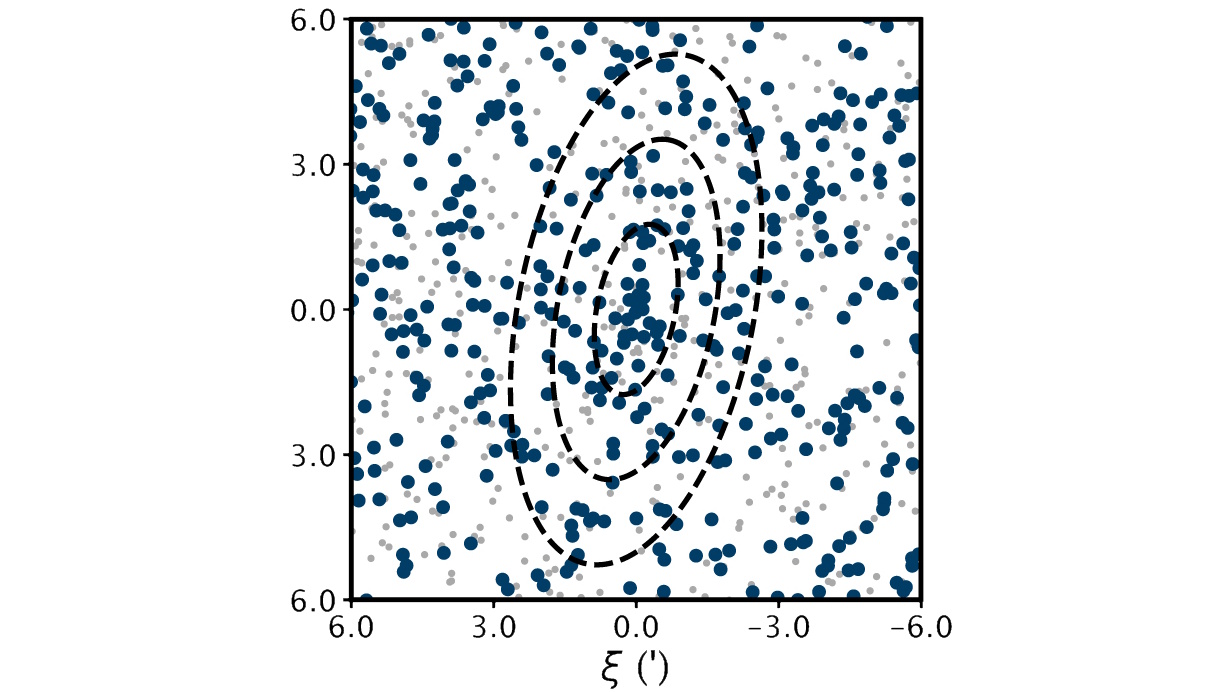

This is why the stars in Messier 35 appear so blue: not only because many of the brightest ones are blue (with many B-class stars still around, all the way up to B3, two full classes bluer than the bluest stars in the Pleiades), but because the stars not in Messier 35 are so much less blue.

And there are plenty of stars in the background of this cluster, including background star clusters galore (including the faint but even bluer IC 2157, off to the west), because the plane of our galaxy is simply where the richest concentrations of stars live.

But it’s also where the richest concentrations of gas live, and one of the things that gas can do is reflect starlight: and that’s preferentially reflecting blue starlight over all the other frequencies. The galactic “fog” we live in is illuminated by the intense blue light emanating from Messier 35, and while there isn’t enough of it to create a true reflection nebula, there is enough that a telescope like the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) can pick it up.

This cluster is located some 2,800 light years away, and is somewhere between 60 million and 110 million years old, depending on a variety of factors. The more distant companion cluster, NGC 2158, is completely unrelated, at nearly a billion years old and at a distance of some 16,000 light years from us.

But what’s ironic is that the brightest stars found in this cluster aren’t the blue ones at all, but rather a smattering of red-to-yellow ones!

That’s because these are giant stars that have evolved from the most massive, blue stars to still be alive; they simply ran out of hydrogen fuel in their core and are now fusing helium! This is the future fate of all the bright blue, white, yellow and orange stars in this cluster, as well as our own Sun. While this cluster may have formed more than four billion years after our own Sun, the most massive stars within it are giving us a preview of what awaits us!

Regardless of what your equipment is, it’s a beautiful sight, one that delights skywatchers of all levels over and over, throughout the year!

This is our next-to-last Messier object before we complete the entire catalogue, so make sure you enjoy this one any time during the year, as it makes for outstanding viewing regardless of light pollution or the presence (or absence) of a Moon. Take a look back at all our previous Messier Mondays below:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M6, The Butterfly Cluster: August 18, 2014

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M16, The Eagle Nebula: October 20, 2014

- M17, The Omega Nebula: October 13, 2014

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M19, The Flattened Fake-out Globular: August 25, 2014

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M22, The Brightest Messier Globular: October 6, 2014

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M24, The Most Curious Object of All: August 4, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M26, The Could-Be-Better Cluster: November 3, 2014

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M28, The Teapot-Dome Cluster: September 8, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M35, An All-Season Cluster: November 17, 2014

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M54, The First Extragalactic Globular: September 22, 2014

- M55, The Most Elusive Globular Cluster: September 29, 2014

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M62, The Galaxy’s First Globular With A Black Hole: August 11, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M69, A Titan in a Teapot: September 1, 2014

- M70, A Miniature Marvel: September 15, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M76, The Little Dumbbell Nebula: November 10, 2014

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

- M110, Messier’s Final Galaxy: October 27, 2014

And come back next week, when we’ll finish the catalogue at last!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!