Messier Monday: The First Extragalactic Globular, M54

Beyond our own galaxy, this ancient relic holds a key to our cannibalistic past.

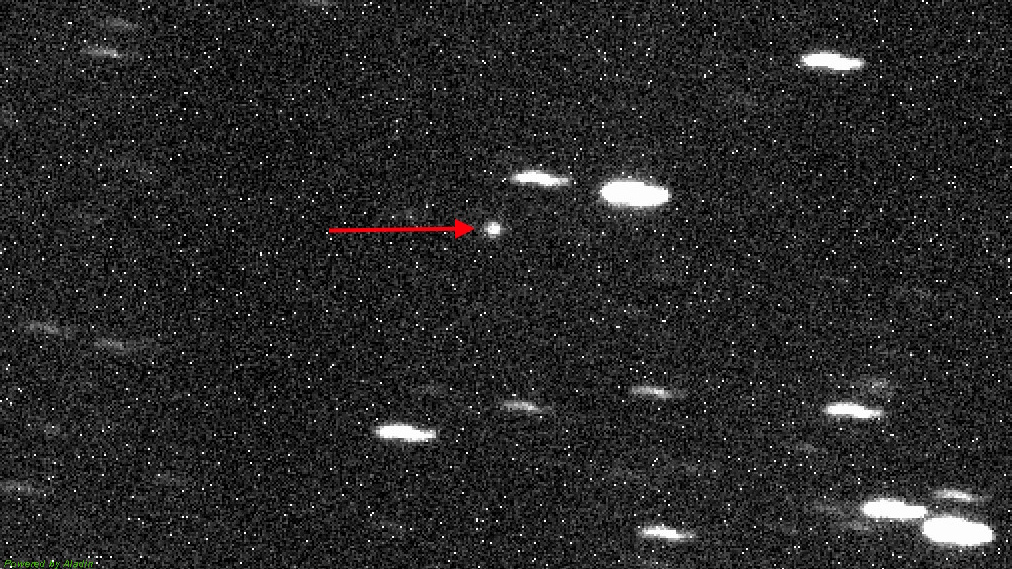

Image credit: NASA / Hubble / Wikisky.

“A hungry man can’t see right or wrong. He just sees food.” –Pearl S. Buck

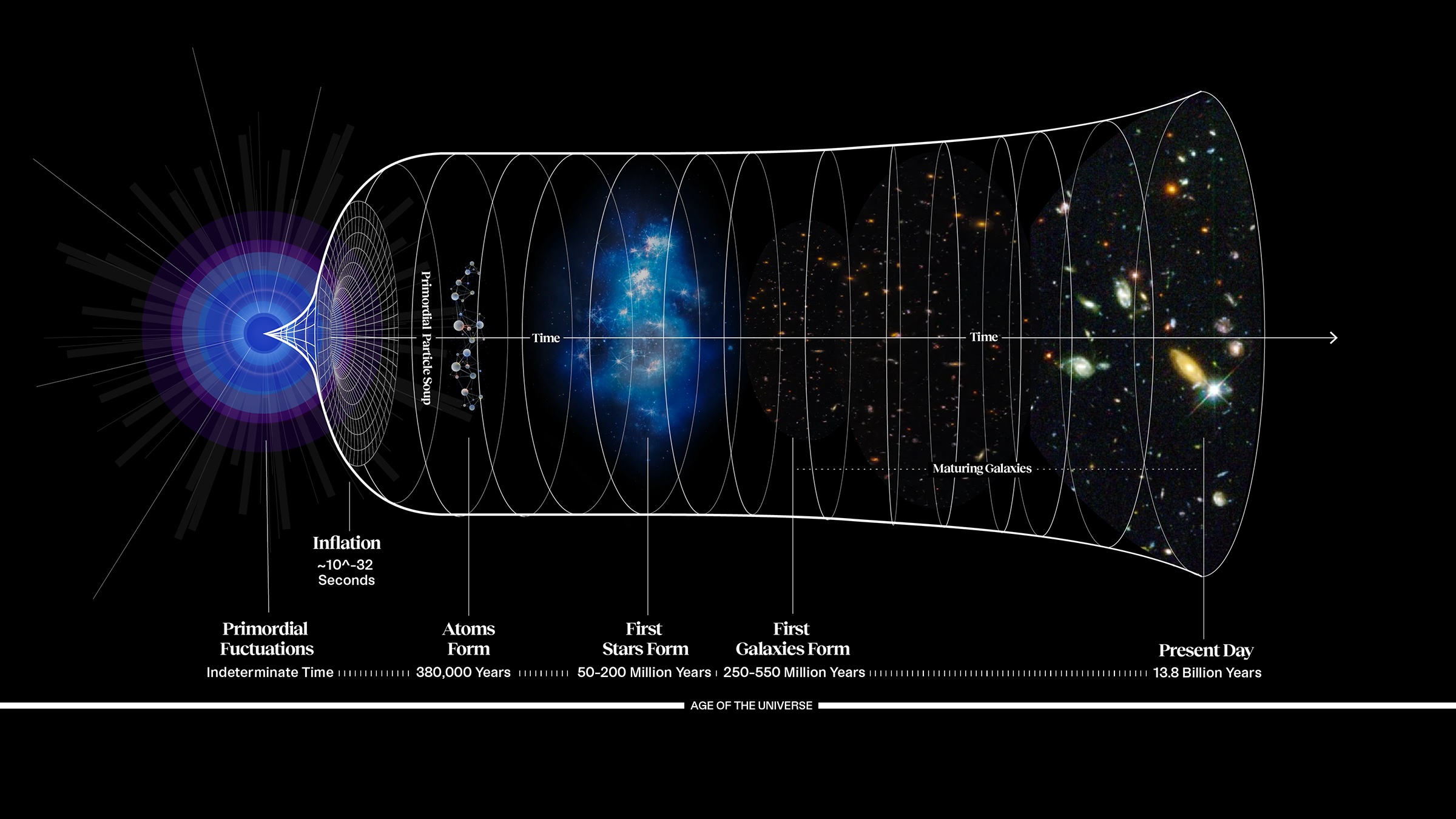

But unlike our bodies, where hunger can be sated by consuming something, a galaxy simply grows hungrier and hungrier the more it eats. When it comes to gravitation, the greater your accumulation of mass, the greater your gravitational force gets. Over the span of billions of years, this explains why the Universe is networked with huge galactic clusters connected by tenuous filaments and separated by vast cosmic voids. And where we are in our little corner of the cosmos, looking up at the night sky from most northern latitudes of Earth, there are 110 deep-sky objects that stand out in a small, amateur telescope more brilliantly than all the rest.

Of all the objects in the Messier catalogue, forty of them are galaxies beyond our own, while the rest are star clusters, nebulae or stellar remnants belonging to our own Milky Way. All of them, that is, except for today’s object: a bright globular cluster that’s beyond our own galaxy!

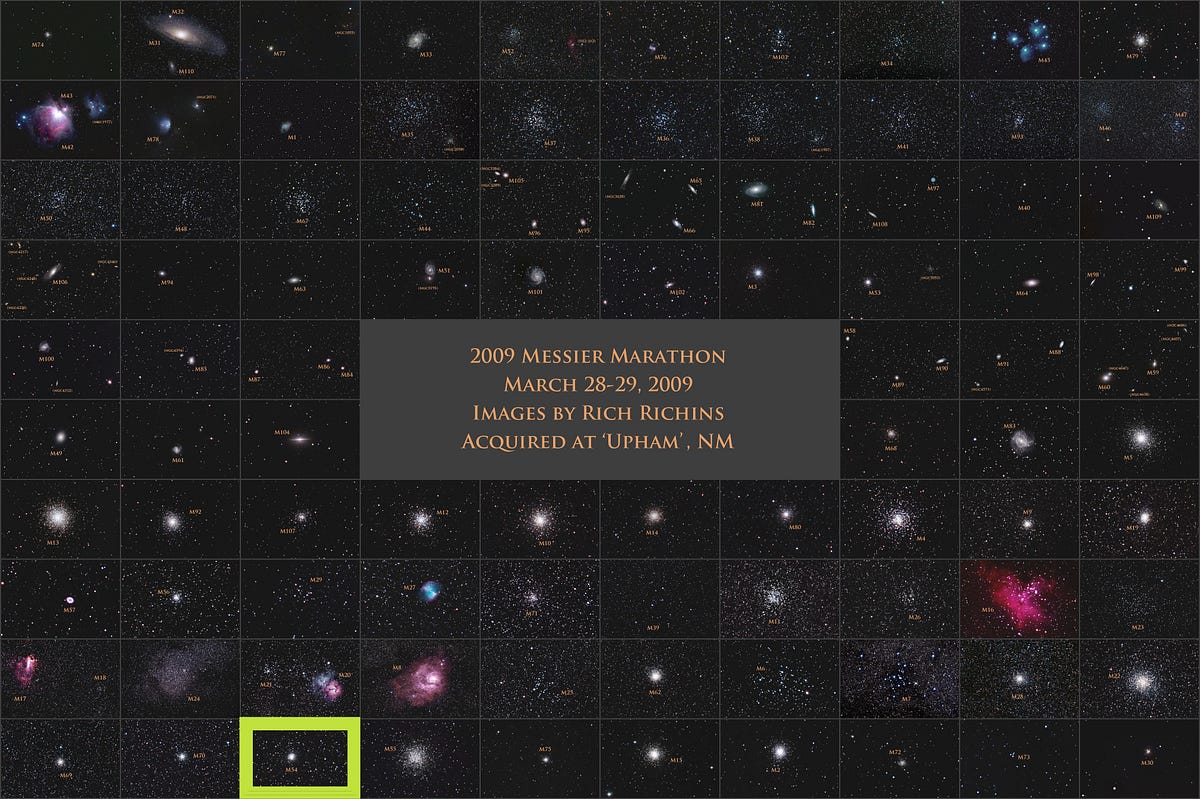

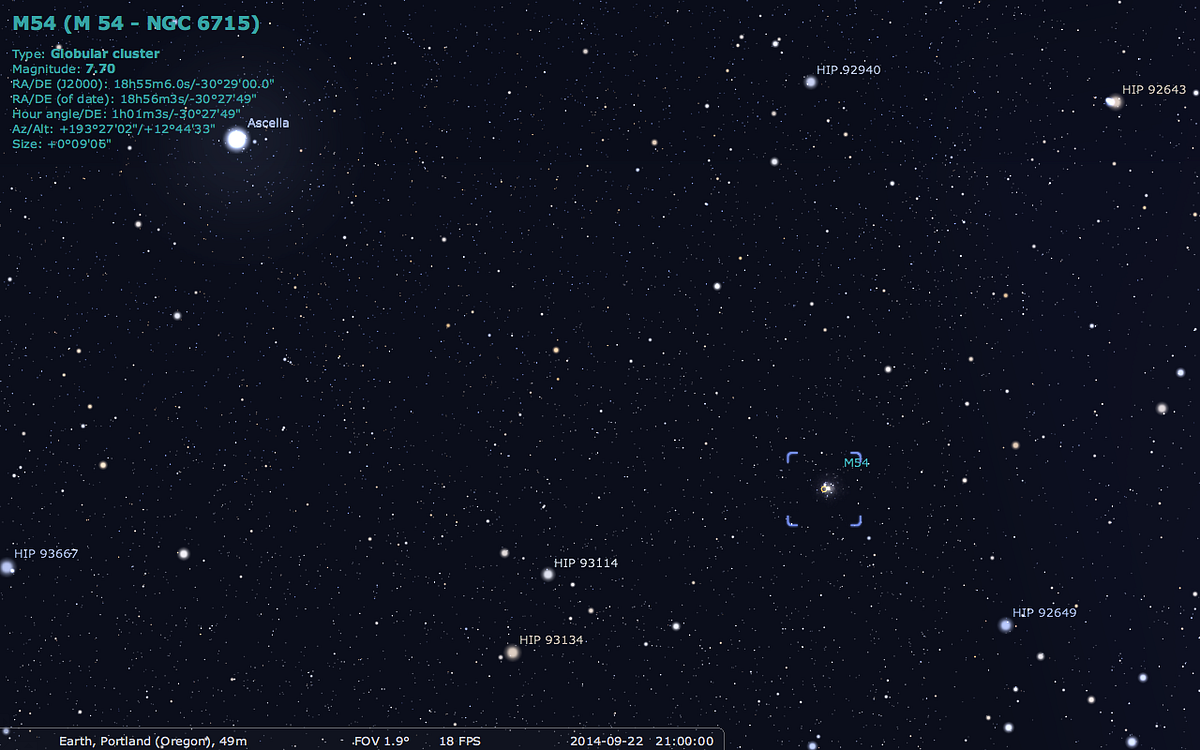

That object is Messier 54, and here’s where you can look to find it.

Shortly after sunset, once the sky darkens, you can look to the south and find the constellation of Sagittarius, which includes the famous asterism of “the teapot,” shown above. With the handle towards the east and the spout towards the west, it’s one of the most recognizably human of star patterns in the sky.

And if you’re looking for the most distant of all Messier globulars, just look towards the star connecting the bottom of the handle to the base: Ascella.

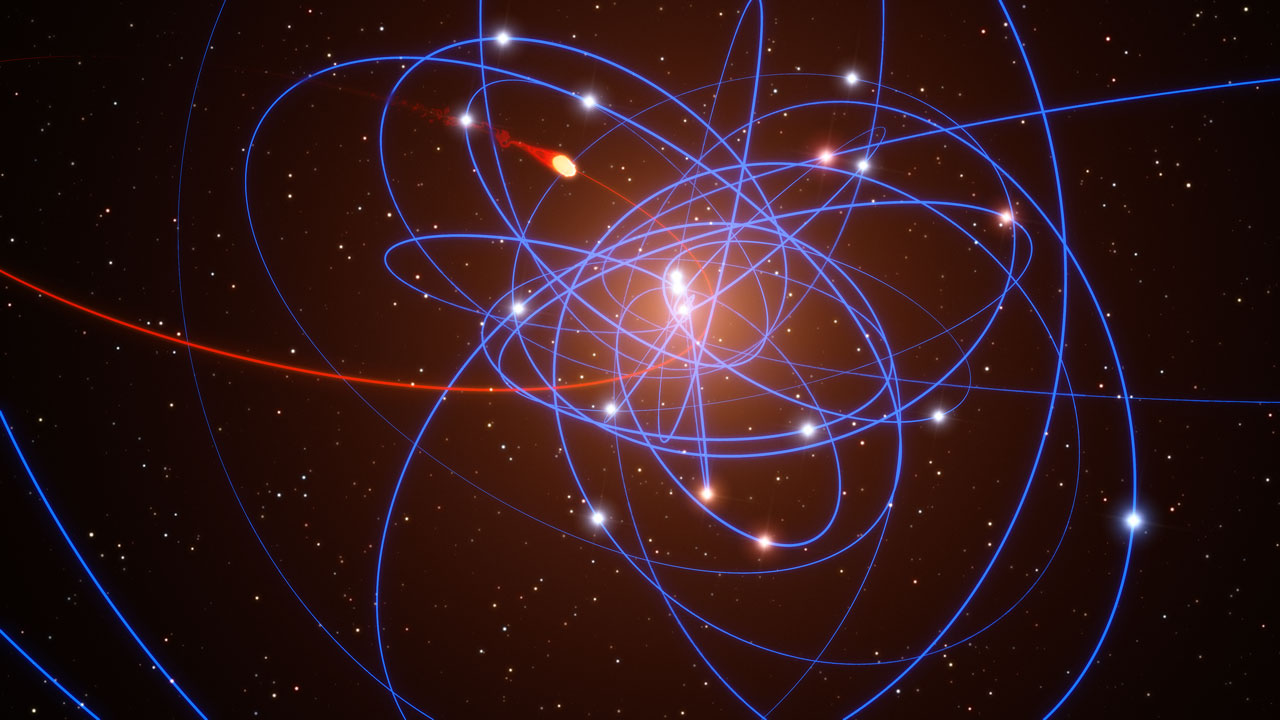

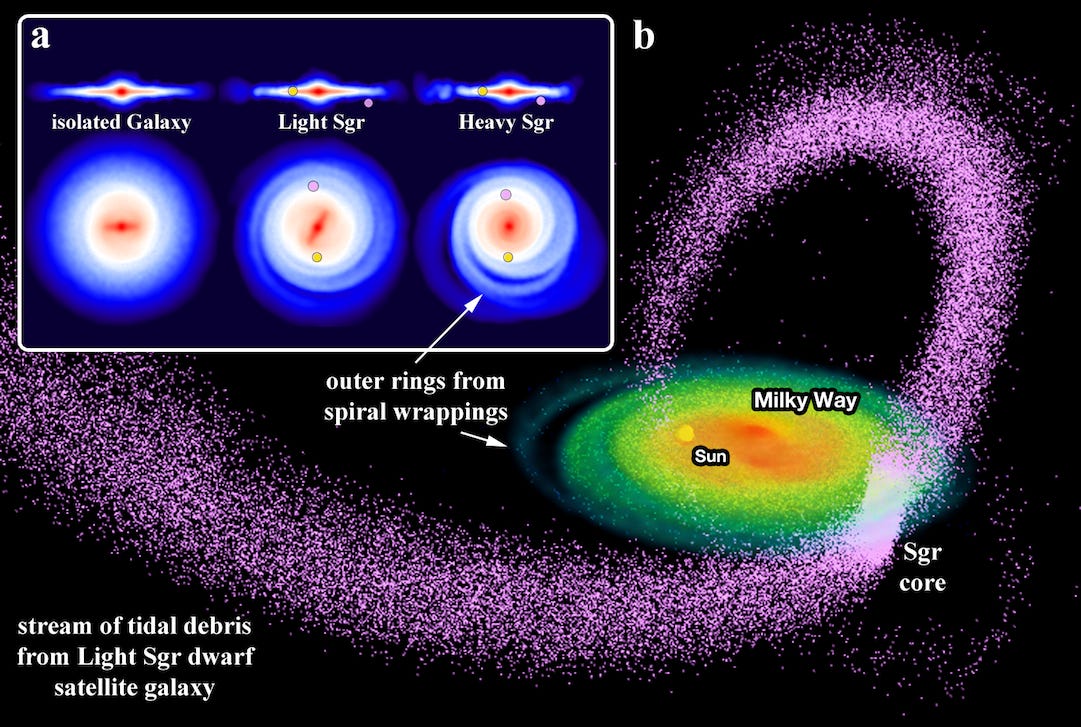

Many deep-sky objects can be found in and around this region of space, as the galactic plane and center run through this constellation. However, Messier 54 is all the more interesting because, despite being located in this part of the sky, it doesn’t have anything to do with our galaxy at all, but rather belongs to one of the dwarf galaxies in our local group, one that’s destined to be eaten by the Milky Way in just a few hundred million years.

In the meantime, we can simply look through the plane of our Milky Way, and see this object clear on the other side.

Just 0.5° south and 1.5° west of Ascella, with the Hipparcos stars shown above flanking it, lies the most distant of all Messier globulars: Messier 54. Unsurprisingly, Messier himself was unable to resolve it into stars, seeing a:

“Very faint nebula, discovered in Sagittarius; its center is brilliant & it contains no star…”

Unlike all the other Messier globulars, even with a relatively good-sized telescope, you’re unlikely to see individual stars when you find it.

What you’re likely to see is a fuzzy but bright central core, gradually fading out as you move towards the outskirts. But just what is it that we’re looking at here?

Most globular clusters are collections of anywhere from a few tens-of-thousands of stars all the way up to a few million stars. They tend to be very dense and clustered around galaxies, with our Milky Way containing about 150–200 total and the largest galaxies — like Messier 87 — containing around 10,000!

While the other globular clusters in the Messier catalogue are members of our Milky Way, it was only in the 1990s that we discovered that this one, M54, is not a part of our own galaxy! While the spiral of our Milky Way might be some 50,000 light-years in radius, with our Sun’s location maybe halfway from the edge to the center, globular clusters are located in a roughly spherical distribution all around the galaxy’s halo.

But unlike the others bound to our galaxy, M54 is some 87,000 light-years distant, and belongs not to the Milky Way, but to the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy, a small satellite of the Milky Way in the slow-and-gradual process of being gobbled up by our own.

It’s traditionally very difficult to see through the plane of the Milky Way, as the intragalactic gas and dust conspires to block most of the visible light. But the path to the core of the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy is fortuitously clear, and allows us to image its core.

Perhaps surprisingly, that’s precisely where Messier 54 resides.

Although it was originally thought that this was the dense, stripped core of the once-proud galaxy, we now believe that Messier 54 instead is and always was a globular cluster: the first globular cluster ever discovered outside our own galaxy! It’s simply the case that globulars tend to migrate towards the center of galaxies thanks to dynamical friction, meaning that the interstellar medium within the galaxy interacted with the moving globular as a “braking force.” Over billions of years, that resulted in this globular cluster winding up at the core of the dwarf galaxy.

And since then, the galaxy has begun to be ripped apart due to its gravitational interactions with the Milky Way, but the dense globular has remained intact!

As far as globulars go, this one’s quite interesting in its own right. It’s one of the most dense types out there, coming in at class III on the I-to-XII concentration scale; it’s very large at 153 light-years in radius; it’s extremely bright, intrinsically, with 850,000 times the luminosity of our own Sun; and finally, it contains multiple stellar populations: the main population that’s approximately 13 billion years old, but four more that (probably) belonged to its parent dwarf elliptical galaxies, that formed 6 billion, 4 billion, 2.3 billion and (most recently) only a few hundred million years ago!

And finally, the very core of the galaxy shows evidence that there’s an intermediate mass black hole of approximately 9,400 solar masses at its core!

This was the first intermediate-mass black hole ever discovered: more massive than could possibly be formed from a single star but far less massive than the million-plus-solar-mass behemoths found at the centers of most galaxies.

What’s amazing is that, over the long term, this galaxy will be completely captured by the Milky Way, but it will likely remain in a very long-period orbit for many billions of years, remaining intact even as its parent galaxy is cannibalized by our own. In the meantime, star formation is probably done in this guy, so the stars we’re seeing inside it now are the largest numbers of stars we’re ever likely to observe. At the highest resolution possible, have a look — thanks to Hubble — for yourself!

That’s more than a million stars shining so brightly at such a distance you might mistake it for a single star through a telescope. But if you look closer — with great magnification — you’ll uncover the unbelievable story of the first globular cluster ever found beyond our own galaxy!

And with that, we wrap up our tenth-to-last Messier object of the whole catalogue! Have a look back at all our previous Messier Mondays:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M6, The Butterfly Cluster: August 18, 2014

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M19, The Flattened Fake-out Globular: August 25, 2014

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M24, The Most Curious Object of All: August 4, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M28, The Teapot-Dome Cluster: September 8, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M54, The First Extragalactic Globular: September 22, 2014

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M62, The Galaxy’s First Globular With A Black Hole: August 11, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M69, A Titan in a Teapot: September 1, 2014

- M70, A Miniature Marvel: September 15, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

And join us next week for another deep-sky wonder and story of the Universe, only here and only on Messier Monday!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!