Messier Monday: The Flattened Fake-out Globular, M19

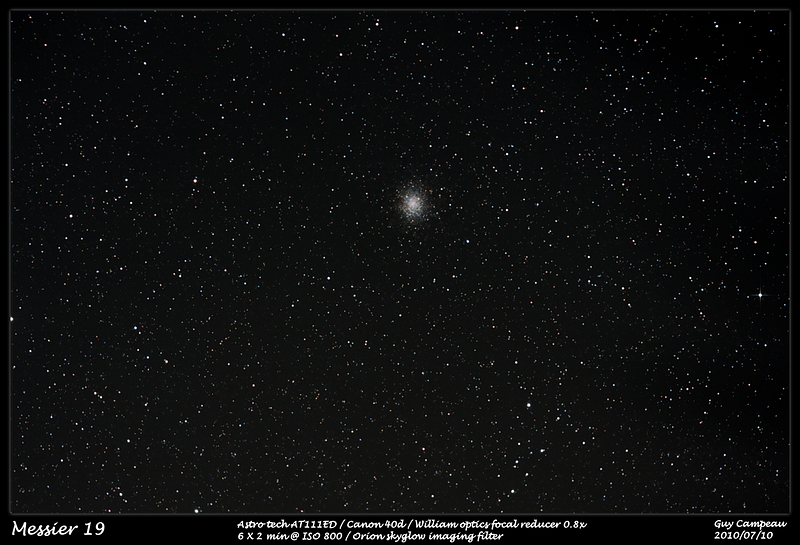

Through a telescope, this swarm of star appears extremely oblate. But is it really?

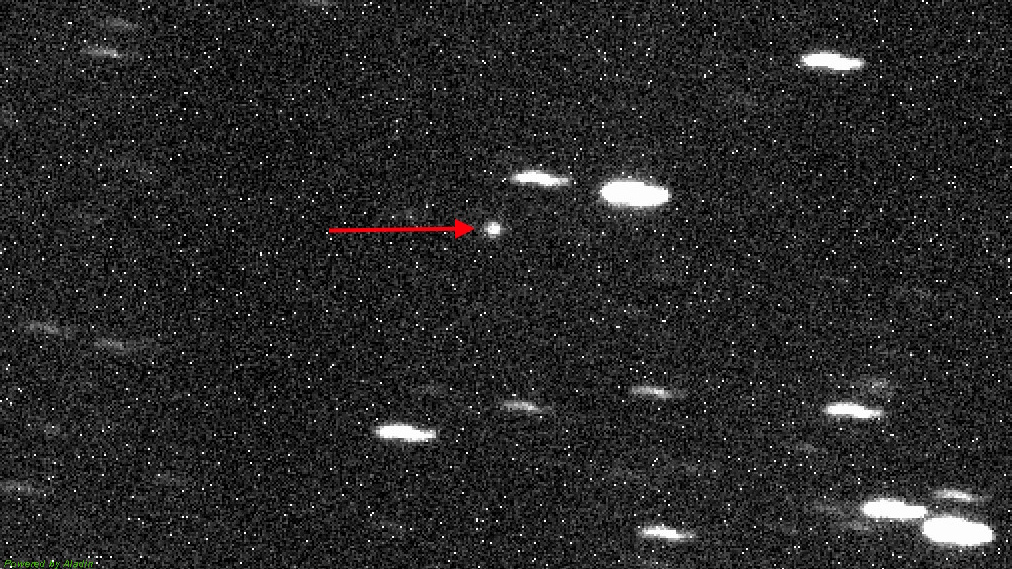

Image credit: via http://vilagbiztonsag.hu/keptar/displayimage.php?album=19&pid=19138.

“If I take dust in my hand and ask you if that is all the dust there is, you will answer that dust is everywhere on earth. More specks than can ever be numbered. So I can give you a handful of truth only. Besides this there are other truths. More than can ever be numbered.” –Nadeem Aslam

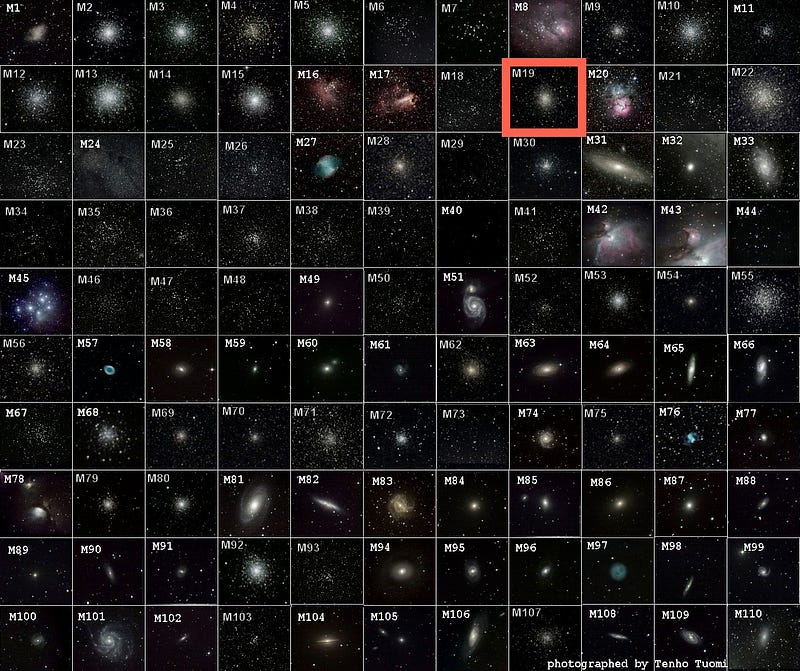

And yet some of the most enduring truths are written not anyplace in this world, but in the heavens above, hundreds, thousands or even millions of light years away. One of the first comprehensive collections of these cosmic stories out there was put together by Charles Messier more than 200 years ago; his 110 deep-sky objects endure as some of the greatest sights visible through a telescope on Earth.

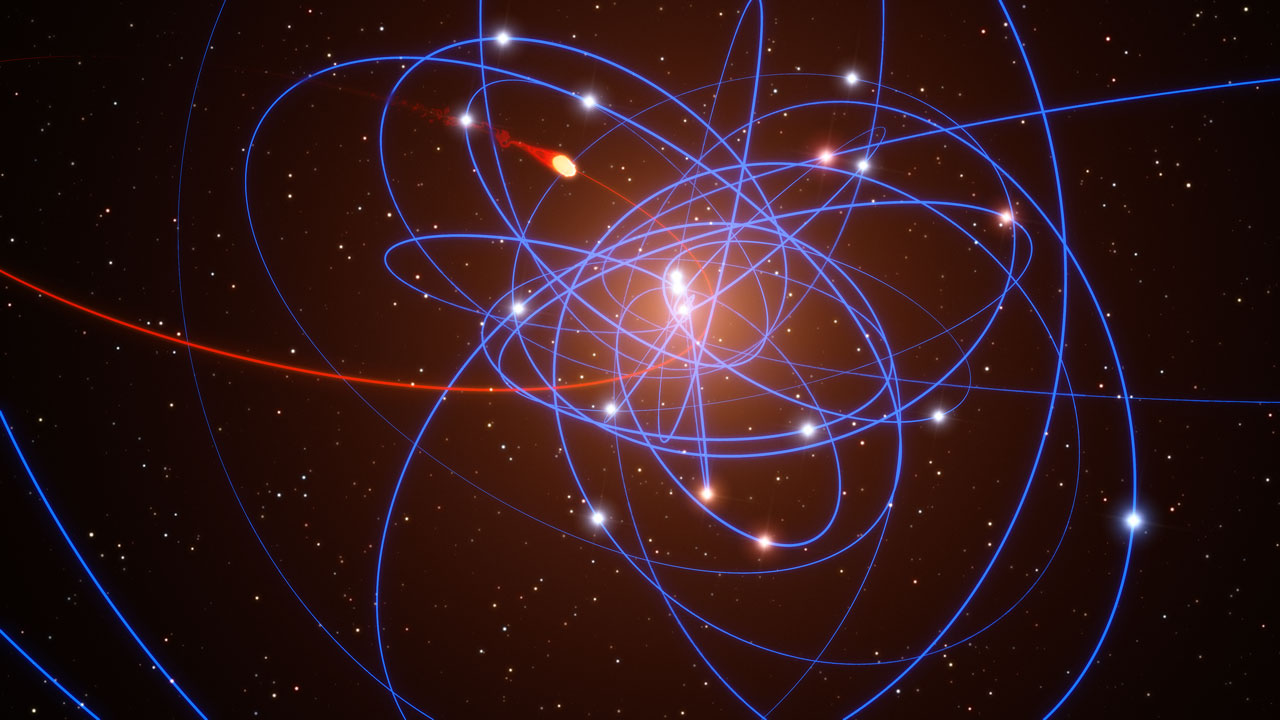

For every galaxy out there in the Universe, there are hundreds — if not thousands — of globular clusters: collections of hundreds of thousands of stars formed billions of years before our own, densely packed into a sphere just a few dozen light-years across. Today’s object, Messier 19, is one of some 200 globulars in our galaxy alone, and one of the most unusual-looking. Here’s how to find it.

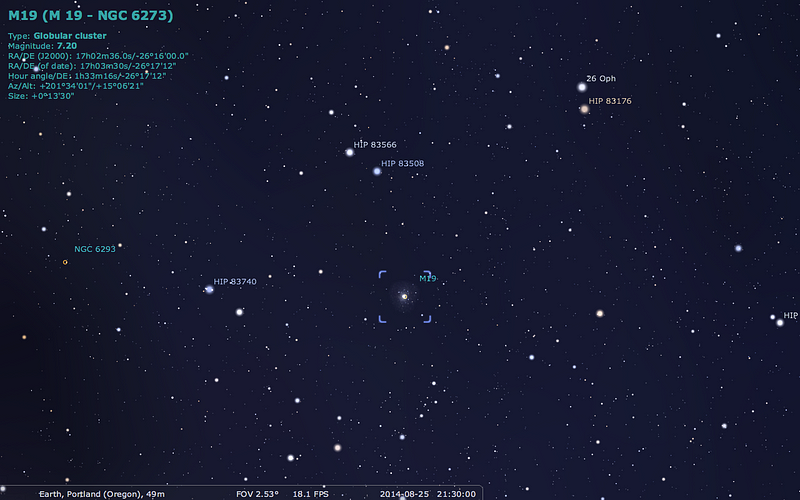

There are a great many Messier objects located in-and-around the constellations of Sagittarius, Ophiuchus and Scorpius, the last of which contains the brilliant orange giant star, Antares. Prominent in the southern part of the sky during the Northern Hemisphere’s summer, this part of the sky is very close to the galactic center and, as such, contains a large number of star clusters.

To find Messier 19, find Antares and look slightly towards the east.

Most prominent of all the stars in that portion of the sky, θ Ophiuchi is a third-magnitude, blue star, and an imaginary line connecting it to Antares will guide you to your destination. About 4.5° west-southwest of θ Ophiuchi, you’ll come to a pattern of stars easily visible in binoculars or a low-power telescope, that has a single star towards the southeast and then two stars close together northwest and two more slightly farther apart just a little farther on towards the west-northwest.

Just south of that first pair of stars, you can’t miss the distinct fuzzball that is Messier 19.

This was one of a great many objects in the catalogue initially discovered by Messier himself, on June 5, 1764, just over 250 years ago. He wrote:

“I have discovered a nebula, situated on the parallel of Antares, between Scorpius and the right foot of Ophiuchus: that nebula is round & doesn’t contain any star.”

Through Messier’s optics, it would have been very difficult to resolve the cluster’s individual stars, or even its non-spherical shape.

But even just a 6″ (150 mm) aperture telescope today is up to the challenge! This globular cluster is located relatively close to the galactic center — just 5,000 light-years away — which is quite close when you consider that we’re some 25,000 light-years distant from the Milky Way’s center! Is that intense gravitational pull from our galaxy’s center responsible for the odd shape of this globular?

Not a chance. Even if this globular cluster was not 5,000 but only 500 light-years from the galactic center, the gravitational force would be woefully insufficient to distort it like this. And this is a highly unusual shape: globulars might vary in how concentrated they are towards they center (on a scale of I-to-XII, with Messier 19 coming in as class VIII), but they’re normally very spherical.

Yet this cluster is very clearly oblate, which means it bulges on its long axis and is compressed along its short axis, similar to planet Earth but on a much more severe scale!

What’s causing this, then? A color image like the one above contains a hint. Do you notice how the stars on the “bulging” sides (top-and-bottom) appear slightly bluer than average? And that the ones on the “flattened” sides (left-and-right) appear slightly yellower/redder than average?

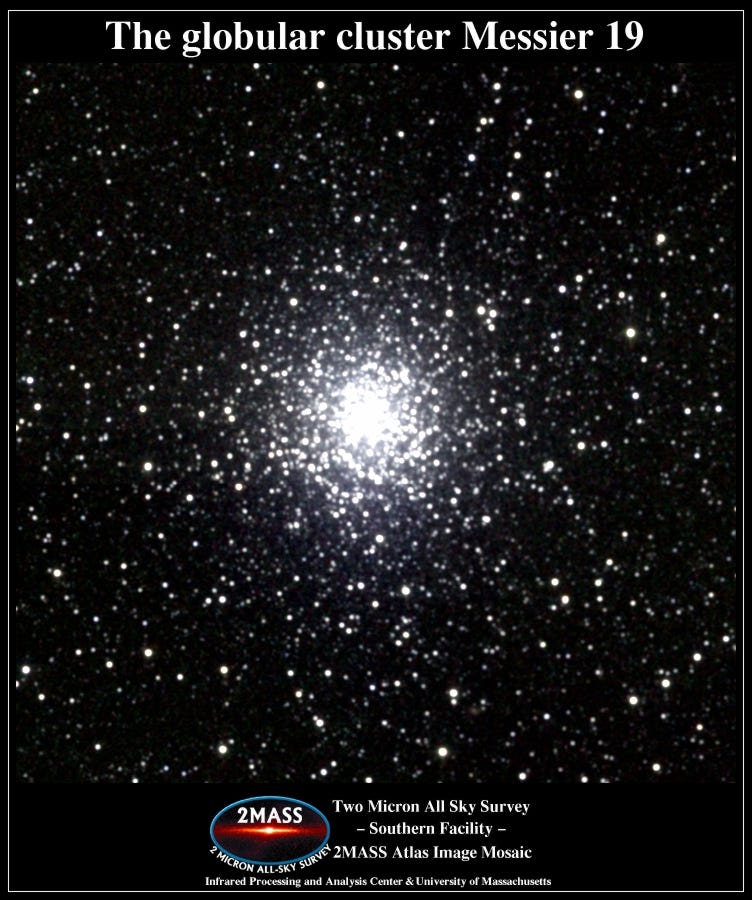

There are tiny dust grains in space, particularly in the galactic plane and especially in the direction of the galactic center. When background light passes through a dusty region, that dust absorbs a portion of the light, but because of the particular sizes of cosmic dust grains and the properties of different wavelengths of light, more blue light and less yellow-to-red light is absorbed by the dust. In fact, if we looked in the infrared portion of the spectrum, where dust has negligible absorptive effects, we ought to be able to see this globular’s “true” shape.

Lo and behold, this globular cluster isn’t flattened at all, but just appears that way because of the unusual configuration of having two dust-rich regions intervening on either side of this object!

In reality, what we’re looking at is a huge globular cluster, some 70 light-years in radius and containing about 1,100,000 times the mass of our Sun inside of it: one of the largest globular clusters in our galaxy! At 29,000 light-years distant, it’s slightly on the other side of the galactic center from us, and its stars are typically about 11.9 billion years old, or nearly three times the age of the Sun.

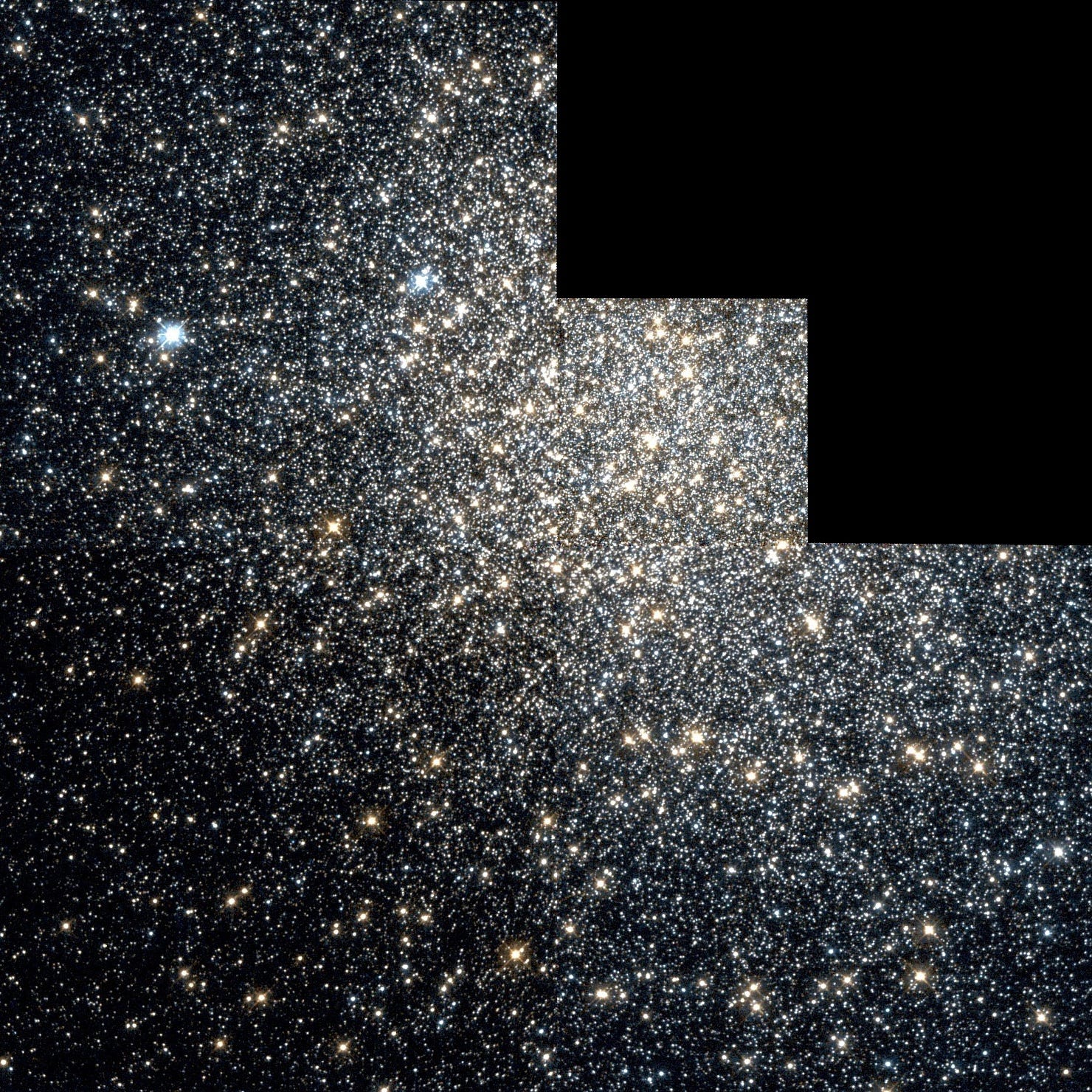

An age like this means that all the class O, B, and A stars that existed in this cluster are long dead, having burned through their fuel billions of years ago. All that ought to still be around are the white, yellow, orange and red stars that are much lower in mass, that burn through their fuel much more slowly. But despite the paucity of blue stars, they still exist, formed by the recent (and fairly frequent) mergers of two smaller stars!

Although Jim Misti’s outstanding photo, above, can’t quite capture it, these mergers (and hence, these blue straggler stars) form most frequently in the globular cluster’s center. That’s something that the Hubble Space Telescope can show us! Have a look:

There are quite a few, but you’ll notice that they’re outnumbered by those bright orange stars you see. What are they? For the most part, they’re red giants, or more evolved stars that are burning helium in their core and nearing the end of their lives. As large globular clusters like this continue to get older, their red giants will live for many hundreds of millions of years, giving us the opportunity to see many hundreds of them all at once. So don’t miss this spectacle of the summer skies; when you know what you’re looking at, the Universe contains all the more to marvel at!

And that will do it for another edition of Messier Monday! Take a look back at all our previous objects here:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M6, The Butterfly Cluster: August 18, 2014

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M19, The Flattened Fake-out Globular: August 25, 2014

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M24, The Most Curious Object of All: August 4, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M62, The Galaxy’s First Globular With A Black Hole: August 11, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

And come back next week, for another deep-sky wonder and another story of the most fascinating, accessible objects in our Universe, only here on Messier Monday!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum over on Scienceblogs!