Messier Monday: The Little Dumbbell Nebula, M76

It’s the faintest and hardest object to see in the entire catalogue, but the rewards — and knowledge you gain — are priceless!

“If there is nothing new under the sun, at least the sun itself is always new, always re-creating itself out of its own inexhaustible fire.” –Michael Sims

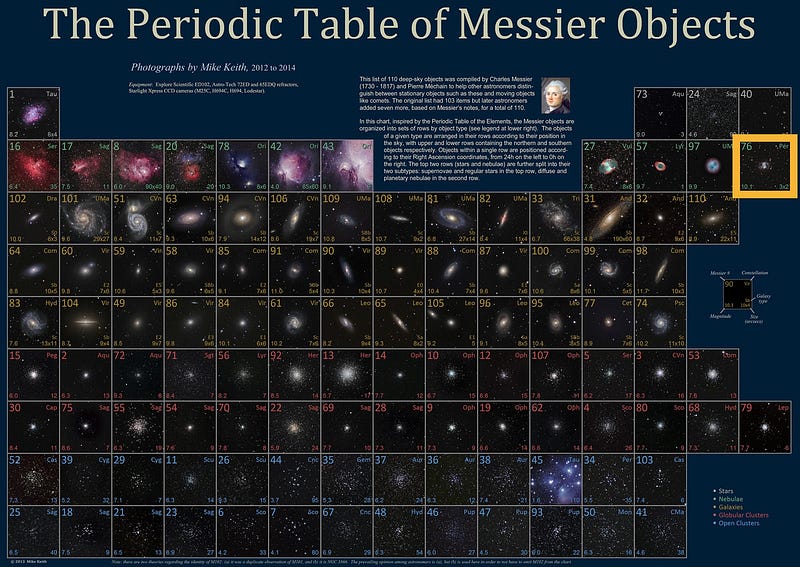

The night sky is a dazzling array of wonders, with thousands of stars visible to the naked eye alone on a clear, dark night. But none of these points of light are going to live forever; none of these cosmic fires — despite the billions or even trillions of years some of them have left to live — will burn forever. And when they do, their ends will be spectacular. Among the 110 deep-sky objects in the Messier catalogue, which consists of many of the brightest and most prominent night sky wonders visible from Earth, only five of them are remnants of dead or dying stars.

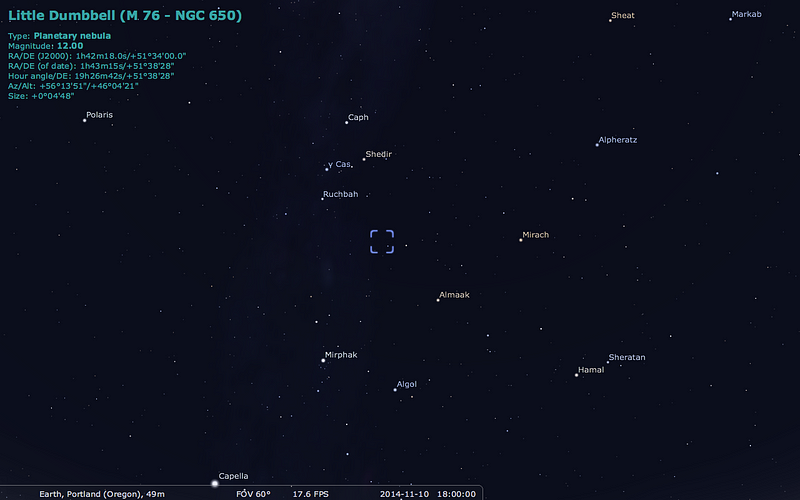

One of them — the Crab Nebula — is an ultra-massive star that died in a supernova, while four others are Sun-like stars that have recently blown off their outer layers while their inner layers contract down to a white dwarf. Today’s object, Messier 76, is known as the Little Dumbbell Nebula due to its resemblance to the brighter Dumbbell Nebula, Messier 27, but it itself happens to be the faintest of all Messier objects! In order to find it, make sure the Moon hasn’t yet risen, and look for the big “W” in Cassiopeia to start.

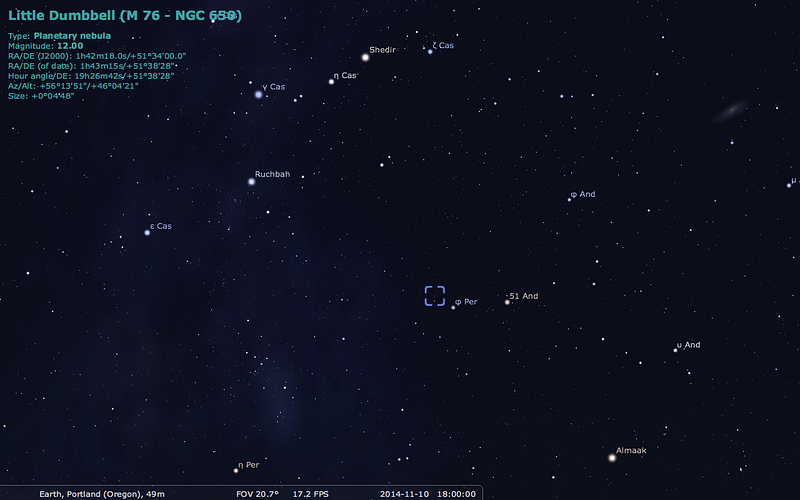

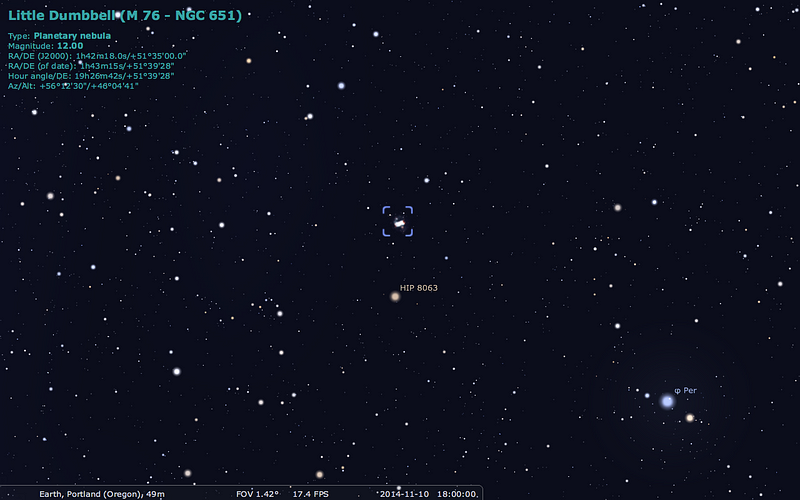

Underneath the “W” are four bright stars in a row: Mirphak, Almaak, Mirach and Alpheratz. The bottom of the first “V” in the “W” is the star Ruchbah, while the relevant star in the line we just took a look at is the second one, Almaak. What you want to do, if you’re searching for this elusive stellar remnant, is to look midway between these two stars, at the imaginary line connecting them.

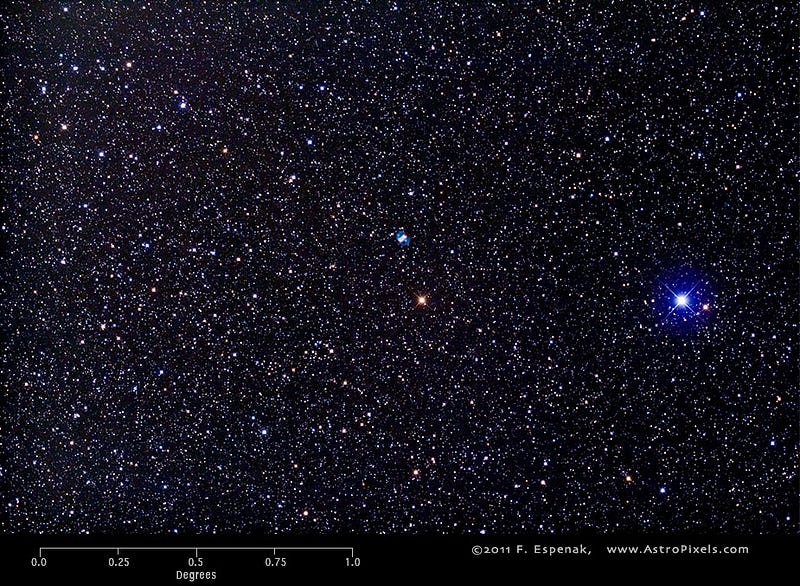

Messier 76 is roughly halfway between them, but it’s incredibly difficult to find without a guide. Lucky, the Universe has given us one in the form of other bright stars easily identifiable in the sky! Almost midway between Ruchbah and Almaak — slightly closer to Almaak — are a pair of prominent stars: the blue φ Andromedae and the orange (and slightly brighter) 51 Andromedae.

If you point your telescope — and don’t even mess around with binoculars unless you’ve got a pair like this — at the blue one, you’re almost there.

Just a little bit east of φ Andromedae is a star right at the limit of human vision under ideal conditions: HIP 8063, an orange giant. And right next to it, just a tiny fraction of a degree north, lies Messier 76, the Little Dumbbell Nebula.

It was barely visible to Messier with the equipment at his disposal, and in fact it was his assistant — Pierre Méchain, who by many accounts was the superior observer — who first discovered it. Here’s Messier’s account:

Nebula at the right foot of Andromeda, seen by M. Méchain on September 5, 1780, & he reports: “This nebula contains no star; it is small and faint”. On the following October 21, M. Messier looked for it with his achromatic telescope, & it seemed to him that it was composed of nothing but small stars, containing nebulosity, & that the least light employed to illuminate the micrometer wires causes it disappear: its position was determined from the star Phi Andromedae, of fourth magnitude.

What’s really amazing about this is the difference you’ll find if you look with simply a monochrome (e.g., unfiltered) eyepiece…

where you can see all the wavelengths of light equally, versus what you can see if you look for light in very particular wavelengths: if you filter by various colors and then stack them together!

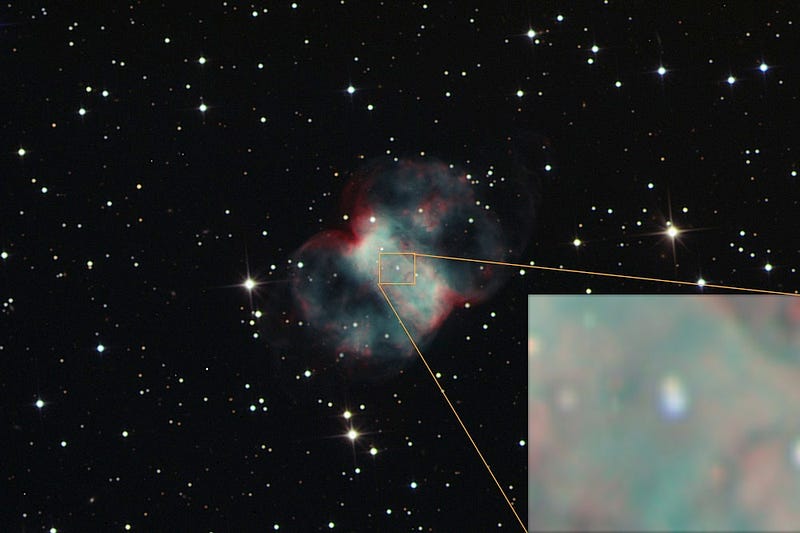

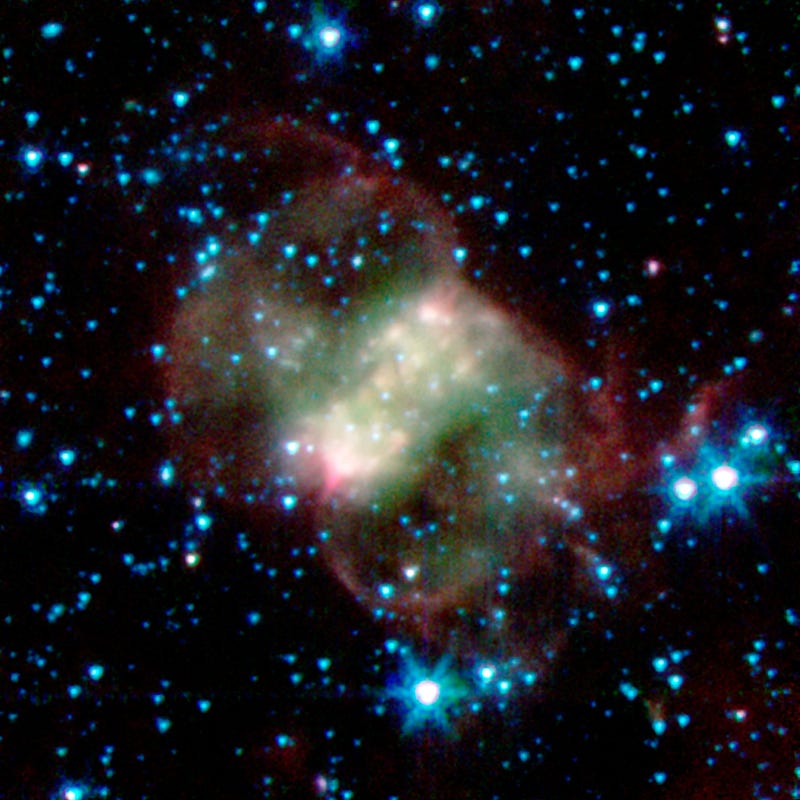

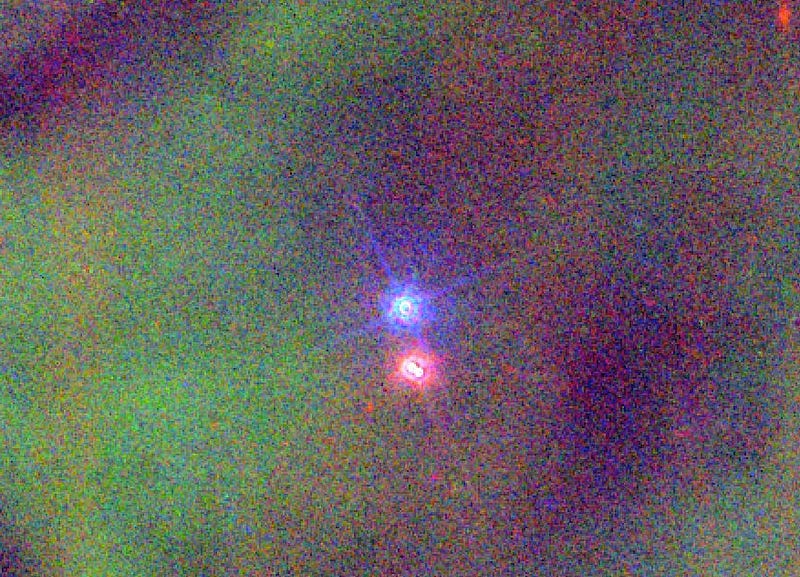

What you’ll find, instead, is an incredibly intricate tapestry of color. Why that’s the case is an even more remarkable story: due to the fact that this was once a Sun-like star — a star that burned hydrogen into helium and then helium into carbon, undergoing a little bit of further fusion into nitrogen, oxygen and neon — that ran out of fuel and then blew off its outer layers, what we’re seeing is a concentration of different elements the farther away we look!

The outer layers, in red, highlight the hydrogen gas from what was once a Sun-like star, while the inner layers in green and blue showcase the regions rich in nitrogen and oxygen.

There’s also an incredibly asymmetric structure to this nebula: something that appears to be two main lobes with a rectangular structure at the center. As it turns out, this is an optical illusion caused by this nebula’s orientation to us. But the right type of view can help us see what’s really going on.

Like many dying stars, this has created a bi-polar planetary nebula, where you get two “lobes” of gas on either side, with a donut-shaped region at the center. Viewed right down the center of one of the lobes, this would look like a ring, but since this is viewed from the side, we see mainly the lighter, rapidly expanding gas farther away with the heavier nitrogen and oxygen closer to the center.

Almost all of the visible light emitted from this nebula comes from a single emission line: the green doubly-ionized oxygen line (O[III]-line) at 500.7 nanometers, with the central star very likely a binary star system. It’s only an orbital system like this — where there are likely two large masses — that are thought to cause a non-spherical nebula like this.

In fact, it’s theorized (and argued) that non-binary systems, like our Sun, might not produce bright planetary nebulae like this, since they won’t have a strong gravitational source to help throw that expanding gas far out into space!

As it stands, the binary star at the heart of the Little Dumbbell Nebula is doing an outstanding job: despite the nebula being only a few arcminutes in size, it’s estimated to be 2,500 light years distant, meaning the visible gas from this star has been flung to a distance greater than a light year in diameter, or more accurately, some 2,000 times the distance that Pluto is from the Sun!

You don’t have to worry about the fact that there might only be one star at the center; there are images out there that clearly show that not only are there two stars at the center of this nebula, but that they’re two different colors! The blue one, by the way, is the one contracting down to become a white dwarf; the color/temperature is a dead giveaway.

As you might expect from the hot, diffuse nebula, its nucleus is at a much higher temperature than any known star would be, with an average gas temperature of around 88,000 K, or around 15 times the surface temperature of our Sun.

Back in the 18th and 19th centuries, it was thought by most that this was two nebulae, but the advent of astrophotography showed that it was, in fact, a single nebula, and (correctly) identified as a planetary nebula approximately only a century ago.

If you look closely for other elements, like sulphur, you can find them as well, as J-P Metsavainio did, below (in the reddish hues) and along the central “donut” part of this nebula.

If we were going to have one nebula that the Hubble Space Telescope could shed some remarkable light on, I would have expected it to be this one. And yet, it never took a wide-field image of this nebula at all. What it did manage to accomplish was to view the very center of this nebula, and find that the “binary star” we identified was actually at least a trinary system!

But there are — fortunately — a great many “amateur” views that are spectacular. I’ve shown you a great many, but here are two more:

and finally, one of my favorites and perhaps the most recent spectacular image of the Little Dumbbell Nebula, Fred Herrmann’s composition for Astronomy Magazine, cropped and enlarged by me, below.

And with that, we come to the end of our final Planetary Nebula for our Messier Monday series, and find ourselves with only two objects left! In the order in which they were added to the catalogue, here are all the Messier objects we’ve covered so far:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M6, The Butterfly Cluster: August 18, 2014

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M9, A Globular from the Galactic Center: July 7, 2014

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M16, The Eagle Nebula: October 20, 2014

- M17, The Omega Nebula: October 13, 2014

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M19, The Flattened Fake-out Globular: August 25, 2014

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M22, The Brightest Messier Globular: October 6, 2014

- M23, A Cluster That Stands Out From The Galaxy: July 14, 2014

- M24, The Most Curious Object of All: August 4, 2014

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M26, The Could-Be-Better Cluster: November 3, 2014

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M28, The Teapot-Dome Cluster: September 8, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M54, The First Extragalactic Globular: September 22, 2014

- M55, The Most Elusive Globular Cluster: September 29, 2014

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M62, The Galaxy’s First Globular With A Black Hole: August 11, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M69, A Titan in a Teapot: September 1, 2014

- M70, A Miniature Marvel: September 15, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M76, The Little Dumbbell Nebula: November 10, 2014

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M80, A Southern Sky Surprise: June 30, 2014

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M89, The Most Perfect Elliptical, July 21, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M100, Virgo’s Final Galaxy, July 28, 2014

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

- M110, Messier’s Final Galaxy: October 27, 2014

So come back next week for our penultimate entry, where a late-rising Moon means a spectacular star cluster — one of the best in the sky — will be your Messier treat!

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!