Ask Ethan: Is the proton stable or unstable?

- One of the most fundamentally interesting observations is the stability of the proton, which must live for at least 10^34 years, or a septillion times greater than the present age of the Universe.

- But the Standard Model doesn’t forbid the proton from decaying, and many Grand Unified Theories predict a lifetime of the proton that’s barely greater than the observed limit.

- There are many ways to constrain the lifetime of the proton, but is it truly, at a fundamental level, stable or unstable? The answer has severe implications for our entire Universe.

There are certain things in the Universe that, if you leave them alone for long enough, will eventually decay away. Other things, no matter how long we wait, have never been observed to decay. This doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re truly stable, only that if they’re unstable, they live longer than a certain measurable limit. While a large number of the particles — both fundamental and composite — are known to be unstable, with some atomic nuclei being unstable but with mean lifetimes far exceeding the present age of the Universe, some particles appear to be truly stable forever, from both observational and theoretical perspectives.

But are they truly, perfectly stable, destined never to decay even as the cosmic clock runs forward for all eternity? Or, if we could wait long enough, would we eventually see some or even all of those particles eventually decay away? And what about the simplest stable composite particle of all, the one at the heart of every atom: the proton? That’s what Patreon supporter kilioopu wants to know, simply inquiring,

“I would be interested in a discussion about proton stability.”

So, what about the proton? Of all the particles in the Universe, the proton is one of the most abundant and important, and has one of the longest experimentally-verified lifetimes of all. But it could fundamentally be unstable on long-enough timescales, with cosmic consequences for nearly everything that exists.

It’s actually a relatively novel idea that any form of matter would be unstable: something that only arose as a necessary explanation for radioactivity, discovered in the late 1800s. Materials that contained certain elements — radium, radon, uranium, etc. — appeared to spontaneously generate their own energy, as though they were powered by some sort of internal engine inherent to their very nature. We’ve now come to terms with how this occurs, as some configurations of the atomic nucleus could, without violating any conservation laws, transition into a more stable, lower-energy state, through either the emission or capture of particles, or simply by quantum tunneling into that more-stable state.

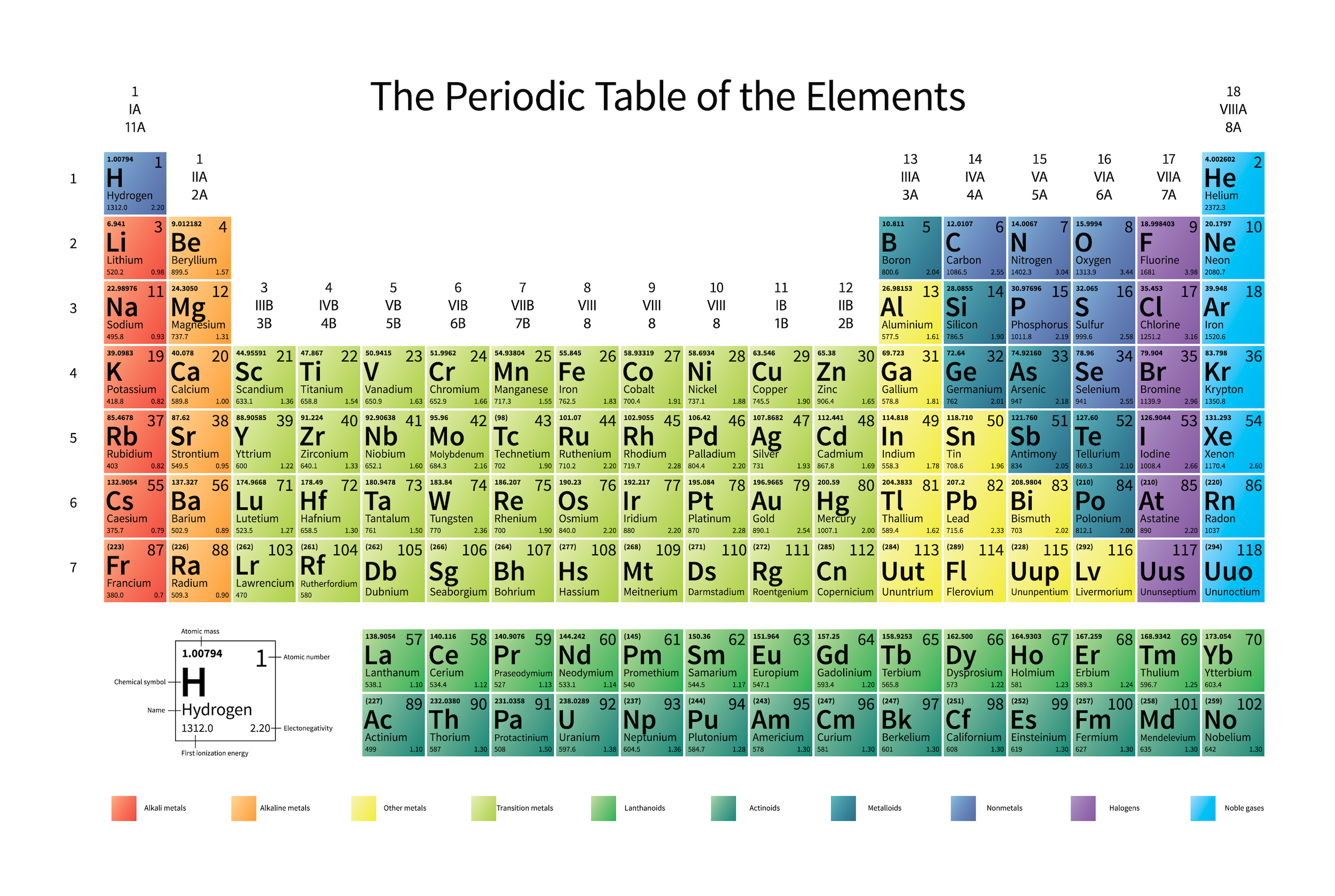

It’s true that much of the matter we know of today will eventually decay away, including:

- every element heavier than lead on the periodic table,

- each particle that contains a strange, charm, bottom or top quark,

- the muon and the tau particle,

- and even the neutron.

It’s enough to make one wonder whether the lightest “stable” composite particle that we know of — the proton — is truly stable after all, or whether it would eventually decay if only we waited long enough.

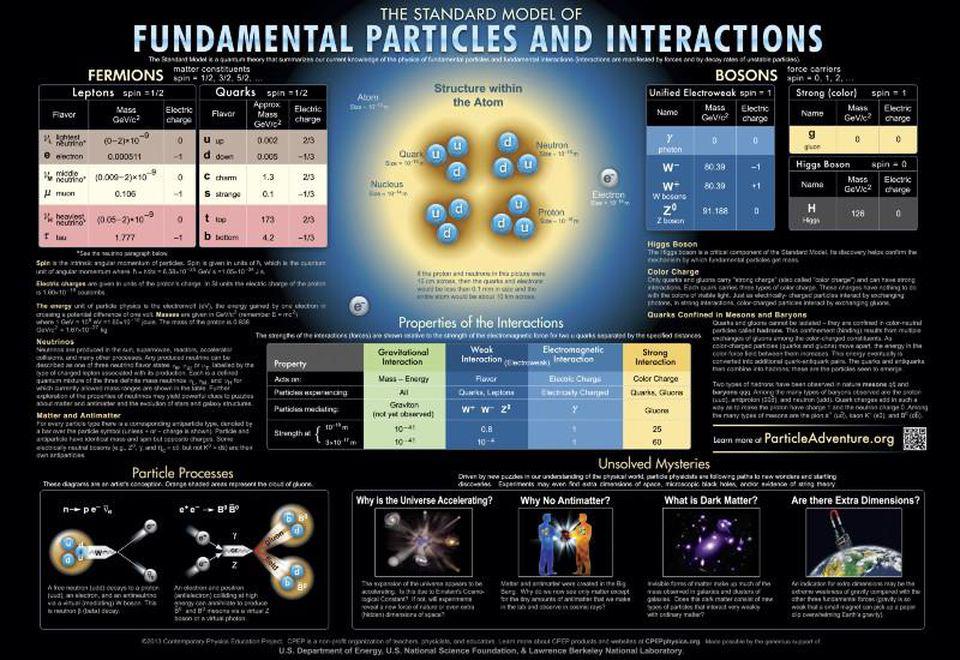

Because of the various conservation laws of particle physics, a proton can only decay into lighter particles than itself. It cannot decay into a neutron or any other combination of three quarks: a collective set of particles known as baryons. Any decay that occurs must conserve electric charge, teaching us that we’d still need to have a positively charged particle (or a set of particles whose net charge was equal to the positive charge of the proton) in the end. And this hypothetical decay, were it to occur in nature, would need to produce at least two particles, rather than one, in order to conserve both energy and momentum.

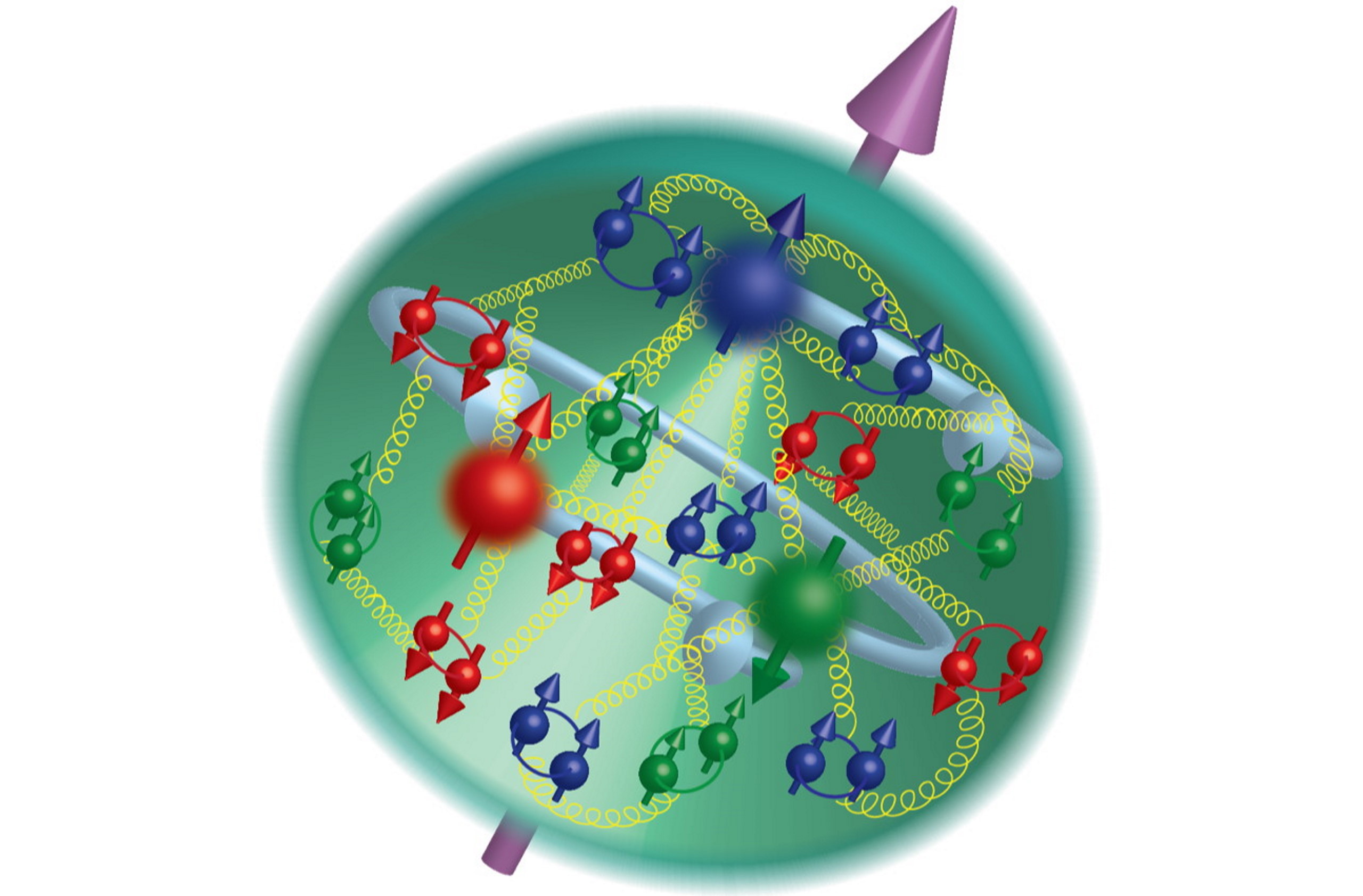

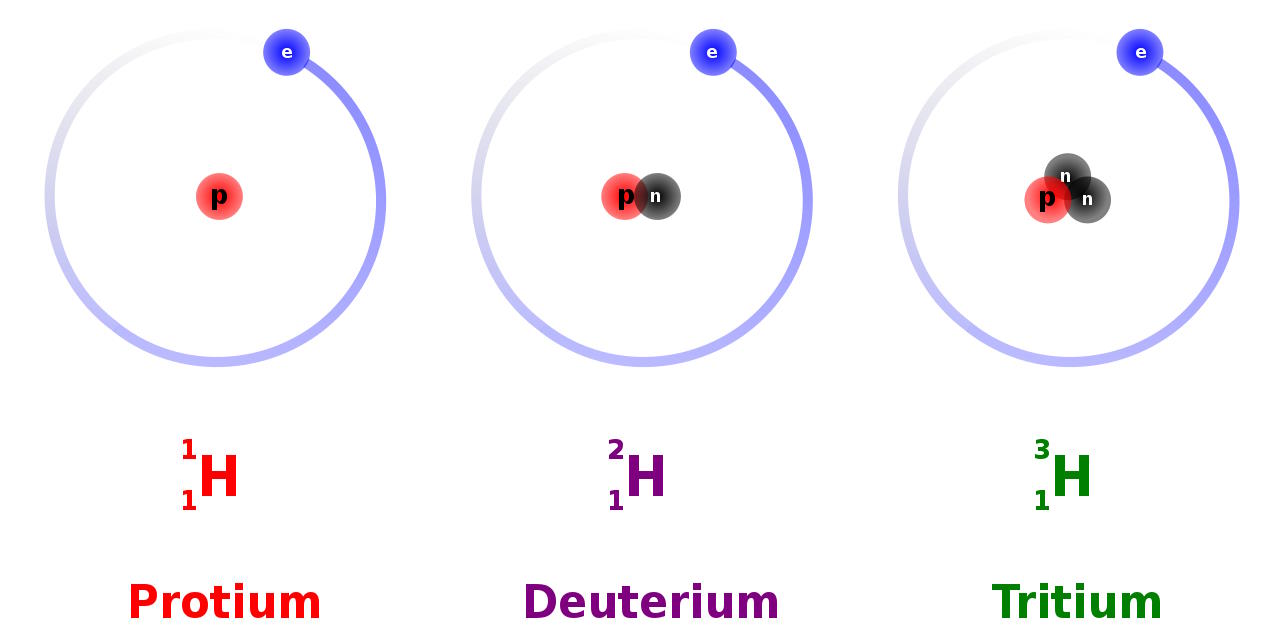

This is a tricky proposition, because the proton is the lightest known baryon, and “baryon number” is something that has never been observed to be violated by particle physics experiments. Each quark has a baryon number of +⅓ and each anti-quark has a baryon number of -⅓, and so far, any experiment or decay ever seen or calculated has the same total number of “baryons minus antibaryons” in its products and its reactants.

However, that’s not a fundamental rule given by the Standard Model of elementary particles. All the Standard Model has, as a constraint on baryon number, is that the combination of “baryon number minus lepton number” must always be conserved, where “lepton number” is the number of charged leptons (electrons, muons, and taus) and neutral leptons (the neutrinos) minus the number of charged antileptons (positrons, anti-muons, and anti-taus) and neutral antileptons (the antineutrinos).

In other words, certain theoretical pathways for the proton to decay are, in fact, available. If we’re going to lose a baryon, like a proton, we can accomplish this in a number of ways that don’t violate any of the necessary known conservation laws. A proton can decay into:

- a charged antilepton (like a positron or an antimuon) and a neutral meson (made of equal parts quark-and-antiquark, such as a neutral pion, a neutral rho particle, a neutral kaon, or a neutral eta particle),

- or a neutral antilepton (one of the antineutrinos) and one of the charged mesons (like a positively charged pion, rho, or kaon).

These hypothetical decays violate some observed conservation laws — such as baryon number, lepton number, and lepton family number — that have never been seen before, but that aren’t explicitly conserved in the Standard Model. All of the things that must be conserved, like energy, momentum, electric charge, and baryon minus lepton number, are still conserved by these hypothetical decays. It might seem, then, like a brilliant strategy would be to gather an enormous number of protons together and build a detector around them that operates for a very long time at very high sensitivity, looking to see if proton decay ever occurs.

Just from your own warm-blooded body, you can learn something fascinating about how stable the proton is. Considering that each one of us is made mostly of a mix of protons and neutrons, we can estimate for an average-sized human being that we have around 2 × 1028 protons apiece inside of us. And yet, in order to maintain our equilibrium temperature as mammals, a typical human has to output about 100 watts of continuous power. That’s the amount of energy-over-time produced by an average adult human under room temperature conditions just to maintain your warm-blooded body temperature.

We know, scientifically, that the way we get our heat energy to maintain our body temperature comes from chemical reactions: from metabolizing the food we eat and burning the reserves of fats that we store. But, just for this exercise, let’s ignore our biological metabolism and make an assumption we know cannot be true: that 100% of our thermal energy comes from the decay of protons in our bodies.

That would imply that, to output this 100 watts of power that keep our bodies warm, about 700 billion protons would decay each second inside each one of us. But given the number of protons we have in us at any given time, that means just 1 in 30 quadrillion protons decays each second. Just from examining our own bodies, this translates into a minimum lifetime for the proton of about 1 billion years.

But we can do much, much better than that by conducting experiments designed to search for proton decay. If all you did was take a single proton and wait around for 13.8 billion years — the entire age of the Universe — you could determine that it’s half-life is likely longer than the total amount of time you waited.

But if you took something like 1030 protons and waited just a single year, if none of them decayed at all you’d be able to say it’s half-life is likely longer than 1030 years. If you gathered 100 times as many protons (1032) and waited for a decade (10 years) instead of just one year, you’d be able to conclude that a proton’s half-life was longer than 1033 years. In short:

- the more protons you gather,

- the more sensitive you are to the decay of even one of them,

- and the longer you wait,

the greater the restrictions you can place on the proton’s stability.

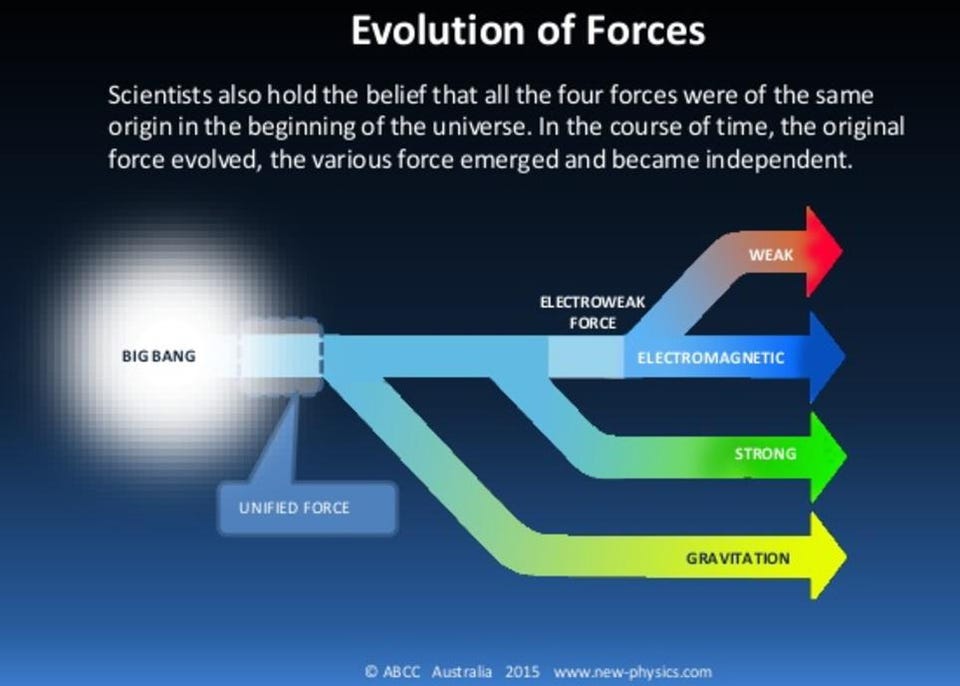

In our current, low-energy Universe, we have four fundamental forces: the gravitational force, the electromagnetic force, and the strong and weak nuclear forces. At high energies, two of those forces — the electromagnetic force and the weak nuclear force — unify and become a single force: the electroweak force. At still higher energies, based on important ideas from group theory in particle physics, it’s theorized that the strong nuclear force unifies with the electroweak force. This idea, called grand unification, would have important consequences for a vital building block of matter: the proton.

This isn’t just some half-baked idea that came about because someone went, “What if the other forces unified at some high energy, too?” Rather, it came about because of an observed puzzle: the Universe appears to be made of matter and not antimatter, and yet the reactions of the Standard Model can only produce matter and antimatter in equal amounts.

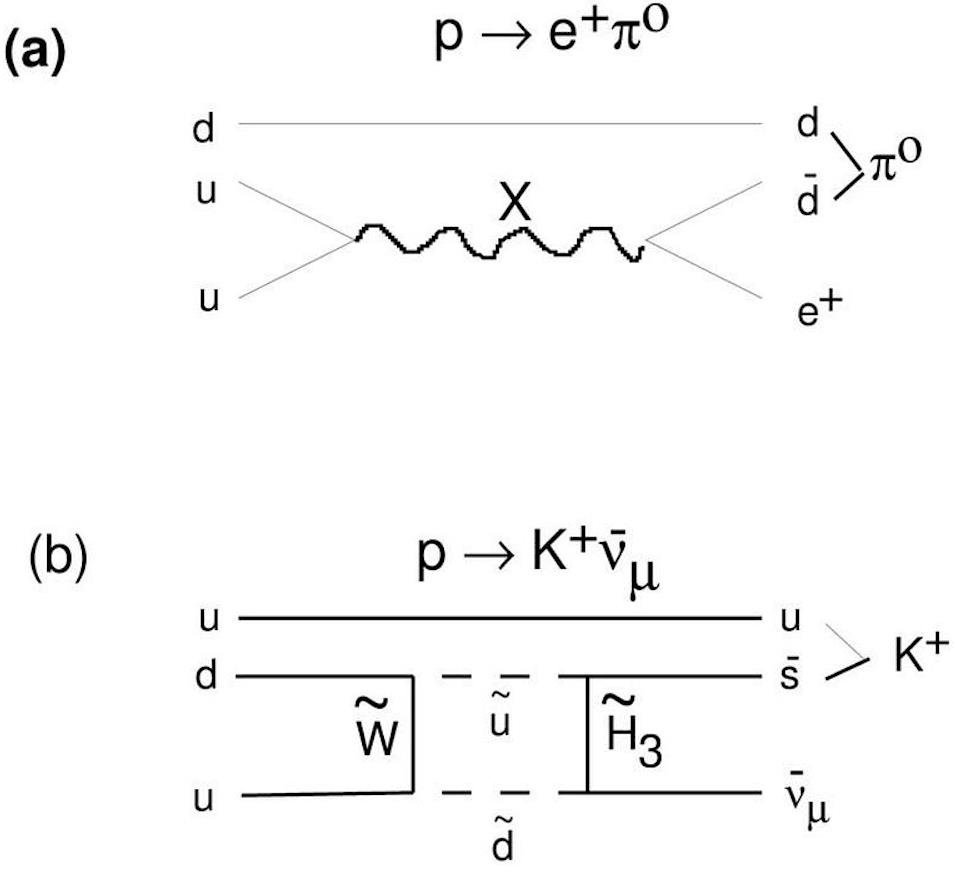

Every scenario that we can concoct to explain this cosmic asymmetry requires the existence of new physics, with every one of them requiring the existence of new particles that will show up at very high energies. In Grand Unification Theories (GUTs), for example, the existence of new, super-heavy X and Y bosons are predicted, and they could solve the puzzle of our Universe’s matter-antimatter asymmetry.

The issue is this: in order to create a matter-antimatter asymmetry, you need a new particle. And the reactions required by that new particle must couple to protons in some way, teaching us that some combination of the proton’s mass (to some power) and the mass of this new particle (to the inverse of that same power) corresponds to the proton’s theoretical lifetime. For most of the models we’ve concocted, that predicted lifetime works out to somewhere between 1031 and 1039 years.

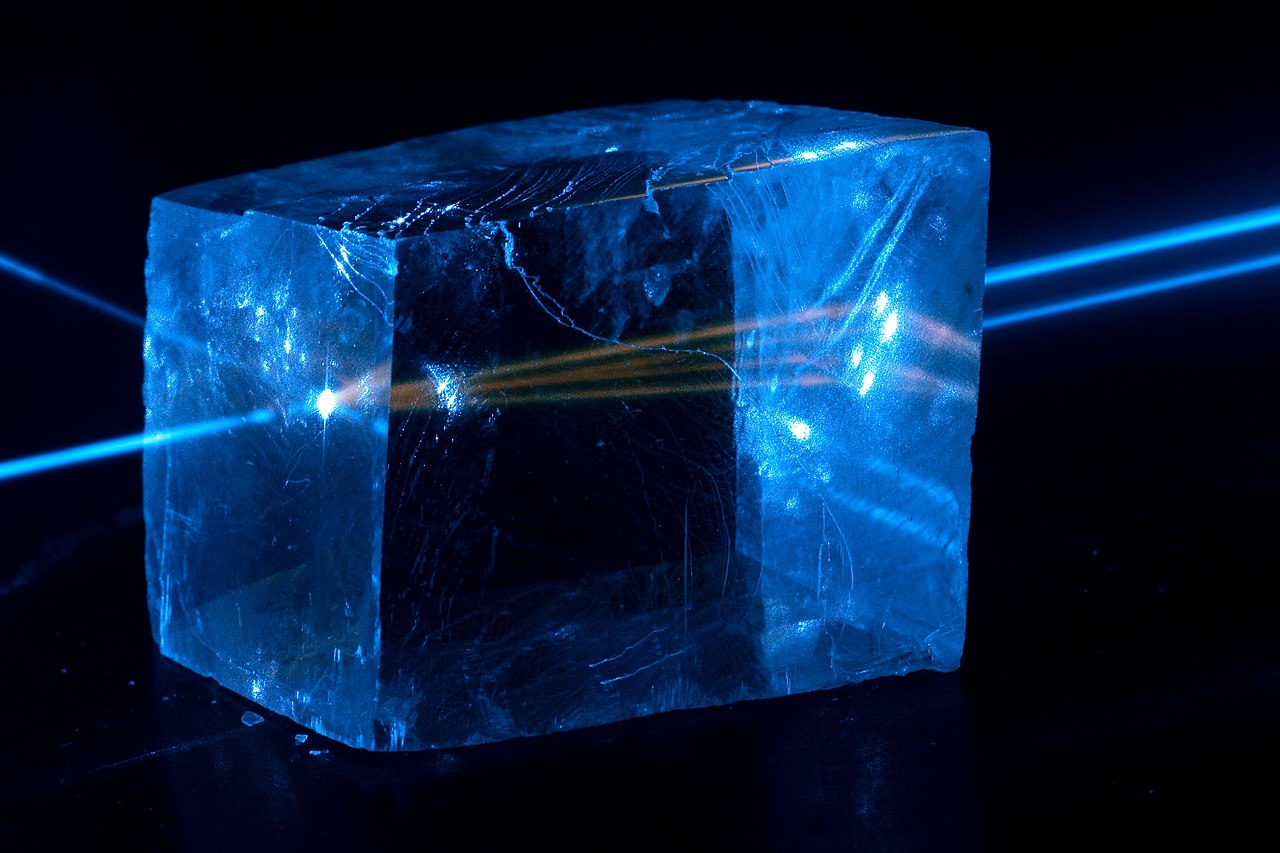

That’s something we can conceivably test! We know that, for example, a liter of water contains slightly over 1025 water molecules in it, and each water molecule contains two hydrogen atoms, which overwhelmingly (in 99.9%+ of cases) is simply a proton orbited by an electron. If that proton were unstable, then a sufficiently large tank of water lined with a sufficiently comprehensive set of detectors around it, should enable you to either:

- measure the lifetime of the proton, which you can do if you have more than 0 decay events,

- or place meaningful constraints on the lifetime of the proton, if you observe that none of them decay.

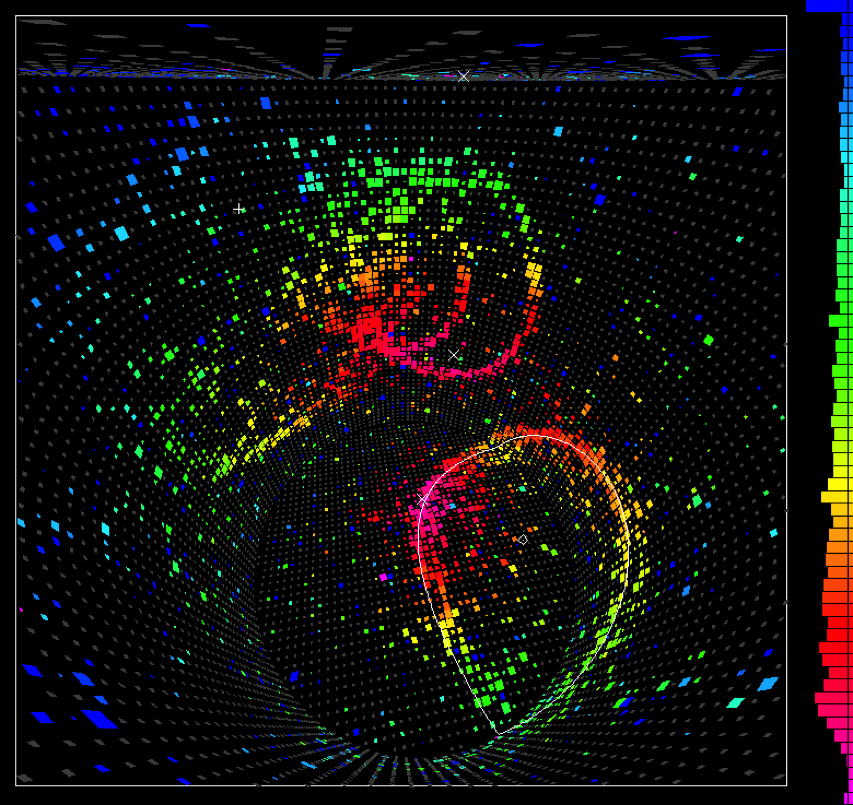

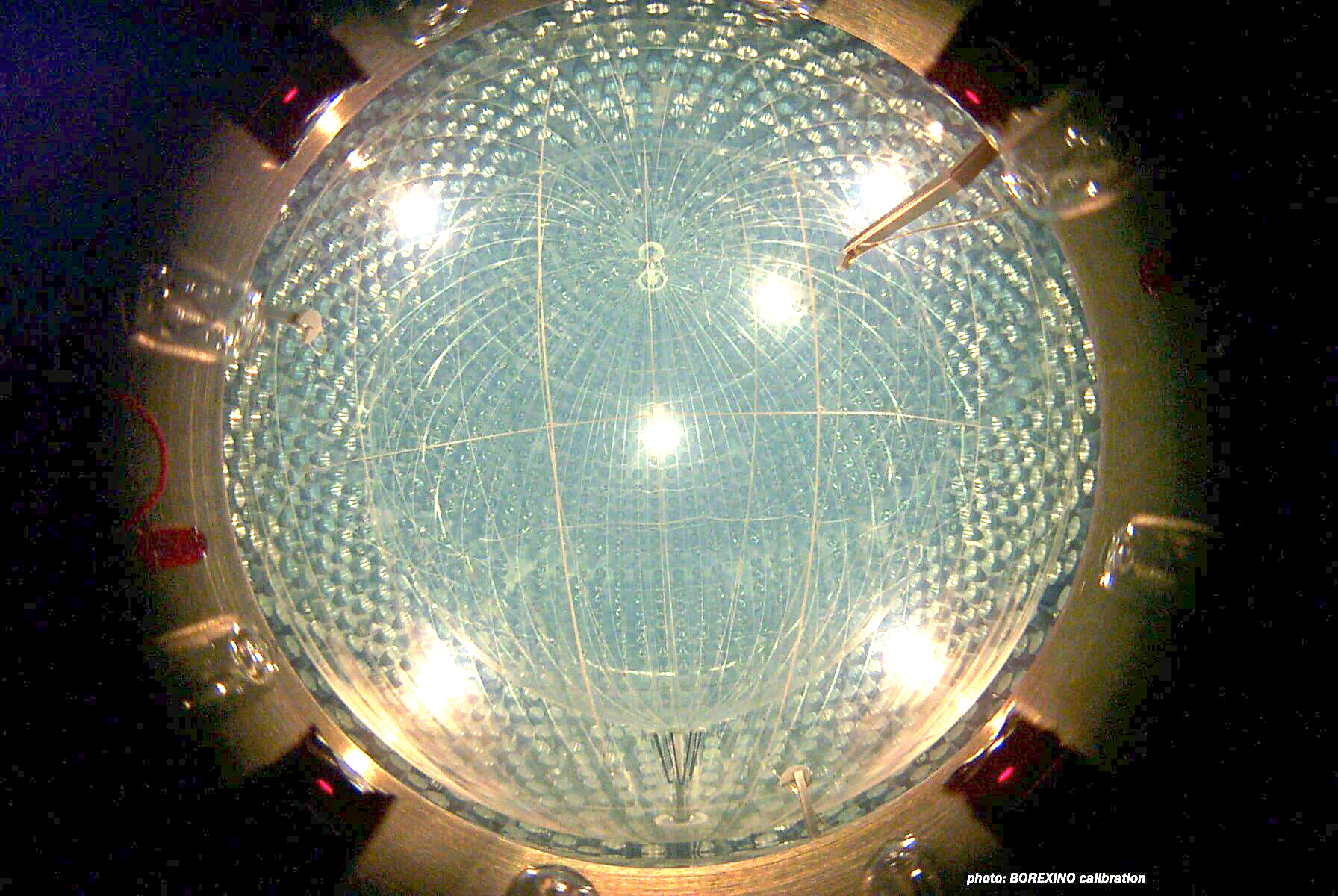

In Japan, in 1982, they began constructing a large underground detector in the Kamioka mines to perform exactly such an experiment. The detector was named KamiokaNDE: Kamioka Nucleon Decay Experiment. It was large enough to hold over 3,000 tons of water, with around a thousand detectors optimized to detect the radiation that fast-moving particles would emit.

By 1987, the detector had been running for years, without a single instance of proton decay. With over 1031 protons in that tank, this null result completely eliminated the most popular model among Grand Unified Theories. The proton, as far as we could tell, doesn’t decay. KamiokaNDE’s main objective was a failure, but it would go on to achieve tremendous scientific success later that year: as a neutrino detector, when supernova SN 1987A went off in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Although these terrestrial proton decay experiments didn’t work out, they wound up having another use: birthing the science of neutrino astronomy.

The modern limits on proton decay are even more restrictive. Recent analyses of data from the 2010s have placed lower limits on the lifetime of a proton that now exceed 1034 years, from both positron and anti-muon decay channels. The simplest Grand Unified Theory models, such as Georgi-Glashow unification, have been thoroughly ruled out unless the Universe is both supersymmetric and contains extra dimensions. Even those scenarios, for which there is no evidence, are predicted to succumb to ongoing data runs by the end of the 2020s.

So, sure: the simplest models of grand unification aren’t right, and the proton’s lifetime is incredibly long: more than a septillion times as long as the current age of the Universe. There is no evidence for extra dimensions, and there’s a lot of strong evidence against nearly all models of low-energy supersymmetry. But we still don’t know the answer to the big question of whether the proton is truly, fundamentally stable or not.

We also need to remind ourselves of a sobering fact: in all of our searches for proton decay, we aren’t actually examining free protons, but rather are examining protons as we find them in nature: bound together as parts of atoms and molecules, even when they’re present as the sole inhabitants of the atomic nucleus. A “free proton” in a hydrogen atom still has about 0.000001% less mass than a proton without an electron bound to it. We already know that while a free neutron decays in about 15 minutes, a neutron bound together in a heavier nucleus can be (for all practical purposes) eternally stable. It’s possible that the protons we’re measuring, because they’re not completely free, might not be indicative of the true proton’s lifetime after all.

Regardless of whether the proton is truly stable forever and ever or “only” stable for a septillion times the current age of the Universe, the only way we’ll figure it out is by performing the critical experiments and watching how the Universe behaves. We have a matter-filled Universe almost completely devoid of antimatter, and nobody knows why. If the proton is unstable, that could be a key clue. But if not, then we’ll need to explore alternative pathways for generating the matter-antimatter asymmetry in our Universe. To the best of our experimental knowledge, the proton remains classified as a stable particle. But everything is experimentally stable right up until the moment it’s observed not to be. For the proton, only time will tell.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!